ARTICLES

The LSD Cult that Transformed America

The Brotherhood of Eternal Love emerged from the hippie culture of ‘60s California – but their ambitions were global. Benjamin Ramm looks at the books and ideas that shaped the group.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of one of the great cultural moments of the last century, the ‘Summer of Love’. It will be commemorated as a season of celebration, but it was triggered by a protest event: the Human Be-In at Golden Gate Park in San Francisco in January 1967, organised in opposition to the prohibition of LSD. State and federal governments argued that the psychedelic drug, also known as acid, threatened the fabric of US life, and they were right – LSD made neither good consumers nor loyal citizens in a time of war. Their adversary was a group of lawless evangelists who had formed a church in devotion to the drug’s transformative power: the Brotherhood of Eternal Love.

The poet Allen Ginsberg (left) was one of the performers at the Human Be-In held in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park on 14 January 1967 (Credit: Getty Images)

The Brotherhood had a template for utopia. It was to be found in the final novel, Island, of the grand philosopher of psychedelics, Aldous Huxley. A prominent advocate for the use of psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms, Huxley was a founding member of a pioneering Harvard project led by Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert. Leary and Alpert supervised the Good Friday Experiment at Marsh Chapel in Boston in April 1962, which found that psilocybin profoundly affected the religious experience of nine out of the 10 graduate students.

Huxley’s imagined society is pacifist, cerebral, sexually experimental, spiritual yet anti-clerical

Island had inspired Leary and Alpert to launch the Zihuatanejo Project, a psychedelic training centre under the umbrella of their International Federation for Internal Freedom. The community was located on the coast of south-west Mexico, and it was here that they began writing The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on The Tibetan Book of the Dead. The book was dedicated to Huxley and cites his 1954 essay The Doors of Perception, which explored the hallucinogenic effects of mescaline, a psychedelic substance found in plants indigenous to Mexico. As the Tibetan Book of the Dead had prepared monks for mortality and reincarnation, so The Psychedelic Experience would teach them how to handle the experience of ‘ego death’ and rebirth.

Island life

Island is a utopian counterpoint to Huxley’s dystopian novel Brave New World. It takes place on a fictional island called Pala, named after a town near Mount Palomar in southern California, where Huxley’s friend Edwin Hubble watched the skies and where members of the Brotherhood took acid. The inhabitants of Pala are enriched by their experiences with psychedelic mushrooms, and they create a society that reflects Huxley’s ideals: pacifist, cerebral, sexually experimental, spiritual yet anti-clerical. The novel is a celebration of living in the moment, and, unlike in Brave New World, drugs are a source of enlightenment and compassion rather than pacification.

Huxley requested a high dosage of LSD in his final hours

The year before publication, Huxley’s home in Los Angeles had been destroyed in a fire that left him, in his own words, “a man without possessions and without a past”. He had been diagnosed with laryngeal cancer, and a key theme in the novel is coming to terms with death, which the islanders do with equanimity. Famously, Huxley requested a high dosage of LSD in his final hours – his wife, who administered the injections, described it as “the most serene, most beautiful death”.

Aldous Huxley’s novel Island is seen as a utopian counterpart to Brave New World. It had a huge impact on the Brotherhood of Eternal Love (Credit: Alamy)

The drug had a similarly profound effect on the petty criminals who would become the Brotherhood, two-thirds of whom had already had run-ins with the law. Their founder, John Griggs, was high on heroin when he robbed a Hollywood producer at gunpoint – but after taking LSD for the first time, he renounced violence, apologised and returned the stolen goods. This transformation is not as strange as it may seem: a research experiment in 1962 by Leary’s Harvard Psilocybin Project suggested that recidivism rates could be cut drastically by treating prisoners with psychedelics.

The King of Tonga was even asked to provide the Brotherhood with a home

Initially, the Brotherhood’s aim had been to ‘drop out’ of society and start anew on an island paradise. “To us, the island represented freedom”, says Edward Padilla, an early member of the group. Many of the Brotherhood favoured settling in Hawaii, while a friend of Padilla flew to the remote Pacific island of Micronesia to scout out territory. The British researcher Michael Hollingshead, who first introduced Leary to LSD at the recommendation of Huxley, even spoke to the King of Tonga about providing the Brotherhood with a home.

The Brotherhood hoped to produce LSD in such huge quantities that it would become virtually free (Credit: Alamy)

It was agreed that the Brotherhood would thrive only if they could survive in isolation, and so they began to experiment in communal self-sufficiency. At Modjeska Canyon in Orange County, the group grew their own crops, wove their own clothes, built their own houses, and even learnt how to deliver babies. “Instead of dropping out of society, they created their own version of it”, says Nicholas Schou, author of a book on the Brotherhood. But they were forced to abandon the settlement after it burned down due to a fire at their makeshift church.

Oh, Brother!

Religion was central to the Brotherhood: they referred to themselves as the ‘disciples’, and believed that LSD could ‘heal and reveal’. Schou notes that the group regarded acid as “a sacrament, a window into God itself, a key to unlock ‘the doors of perception’”. Robert Ackerly, who represented the Brotherhood in San Francisco’s hippy Haight-Ashbury district, “felt we were doing God’s work”. A practical reason for registering as a church was to seek religious exemption from prohibition – a strategy pursued by Leary’s own League of Spiritual Discovery.

Acid was taken in such quantities that the Hells’ Angels were asked to run the crèche

In protesting the prohibition, the Human Be-In was fuelled by LSD – acid was taken in such quantities that the Hells’ Angels were asked to run the crèche. Up to 30,000 people heard Leary make a speech in which coined the slogan “Turn on, tune in, drop out”. The Be-In featured poetry from Allen Ginsberg and music from Jefferson Airplane and The Grateful Dead, and inspired a series of imitation events (Love-In, Bed-In).

Timothy Leary’s philosophy of mind expansion through psychedelic drugs made him a messiah of the 1960s counterculture (Credit: Alamy)

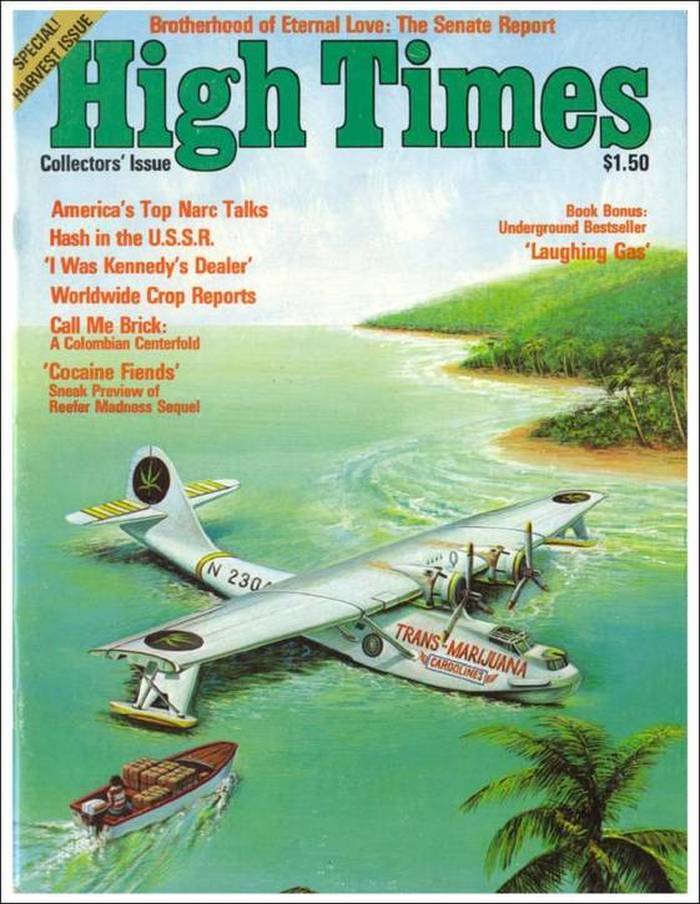

The Brotherhood began to distribute – often for free – their own brand of LSD called Orange Sunshine, with funds raised from the smuggling of Afghan hashish, which they brought directly from Kabul and Kandahar, via Karachi, Istanbul, Frankfurt and London. It was an audacious global smuggling operation, with drugs stashed in musical instruments, in a VW camper van, and, in quintessentially Californian style, inside hollowed-out surfboards. Communion with the waves was a core part of the Brotherhood’s spiritual identity – they referred to it as ‘Christ in the Curl’.

Hard comedown

The Brotherhood’s religious inspirations were diverse, from the I Ching to Leary’s Psychedelic Prayers, and strongly favoured the eastern concepts practiced by the islanders of Huxley’s Pala. In Laguna Beach, the group opened a ‘psychedelic emporium’ called Mystic Arts World, in which all the corners were rounded, as stipulated by the Book of Tao. It was in front of this shop that Leary launched his ill-fated bid to be governor of California against Ronald Reagan in 1969, for which John Lennon wrote the campaign song Come Together.

The members of the Brotherhood saw themselves in a quest for human emancipation; law enforcement officials saw it differently (Credit: California Department of Justice)

Seeking privacy, some of the Brotherhood moved inland to a ranch near Idyllwild, to create a couples-only commune led by Leary, who declared that he and Griggs were ‘agents of God’, born to lead ‘a new breed’. Then, at the age of 25, Griggs died of an overdose of psilocybin crystals. The Brotherhood responded by redoubling their commitment, and expanded their operations to produce 10kg of LSD – approximately 100 million doses. According to Michael Randall, a formative member of the Brotherhood, the plan was to drive down the price of LSD through mass production – to distribute “so much Orange Sunshine that it would become virtually free. We had a deep spiritual commitment to what we were doing”.

They dropped 25,000 tabs of acid from a plane onto revellers on the beach below

Brotherhood members, christened the ‘Hippie Mafia’ by the police, used multiple identities to evade detection, but remained socially and politically influential. In 1970, after helping Leary escape a Californian jail, the Brotherhood gave $25,000 to the Black Panthers, who in turn passed it on to the radical left-wing group, the Weather Underground, to smuggle Leary to Algeria and then to Afghanistan. During a three-day ‘happening’ in Laguna Beach – a riotous birthday party for Jesus Christ that began on Christmas Day, 1970 – the Brotherhood dropped 25,000 tabs of acid from a plane onto revellers, in a concerted attempt at communal spiritual revolution.

The Brotherhood featured in the 1972 film Rainbow Bridge, intended as a rejoinder to the dark side of the hippie lifestyle shown in Easy Rider (Credit: Antahkarana Productions)

The group’s celebrity also inspired one of the strangest films ever made, Rainbow Bridge (1972). It features Jimi Hendrix’s final recorded US performance, given exclusively to the Brotherhood at the top of a volcano in Maui, Hawaii. The movie glamourised the group’s activities, which included creating a strain of cannabis called Maui Wowie, but it also revealed their surfboard ruse, to the dismay of some Brotherhood members. The film is a distinctly hippie creation (“Let’s make love…You can’t make love – love is!”), but it was not well-received: one critic described the film as “a ludicrous farrago of pseudo-mystical acid babble devoid of sincerity… the best thing that can be said about Rainbow Bridge is that, after seventy-one minutes, it finishes”.

They’re a bunch of loose cannons on a ship of fools – Owsley Stanley

Not everyone viewed the Brotherhood’s activities as a form of emancipation. In his final annual address to Congress in 1968, President Lyndon Johnson denounced drug distribution, saying “The time has come to stop the sale of slavery to the young”. Owsley Stanley, who made LSD into tablet form for the acid tests of writer Ken Kesey, described the Brotherhood as “loose cannons on a ship of fools”. Richard Alpert, who renamed himself Ram Dass (‘servant of God’) after meeting his guru in India, was wary of the group’s ambition: “They were rebellious and wanted to use psychedelics to challenge the government. They had the tiger by the tail”.

By contrast, Leary believed he was a modern messiah, describing himself as "the wisest man of the 20th Century". He became a divisive figure within the Brotherhood itself, in part because he didn’t share the vision of a surf-rich island utopia. Ultimately, it was Nixon’s war on drugs that undid the Brotherhood, along with the increasing popularity of an alternative ‘unspiritual’ narcotic: cocaine.

Fifty years after the Summer of Love, psychedelics are attracting the attention of the group they first inspired – medical researchers. In the novel Island, a character experiences a ‘good’ death after taking psychedelics, just as Huxley did. Projects at New York University and John Hopkins University are now exploring the effects of psilocybin in palliative care for cancer patients. Huxley’s vision, which has lain dormant for half a century, may yet come to fruition.

- By Benjamin Ramm, 12 January 2017

This year marks the 50th anniversary of one of the great cultural moments of the last century, the ‘Summer of Love’. It will be commemorated as a season of celebration, but it was triggered by a protest event: the Human Be-In at Golden Gate Park in San Francisco in January 1967, organised in opposition to the prohibition of LSD. State and federal governments argued that the psychedelic drug, also known as acid, threatened the fabric of US life, and they were right – LSD made neither good consumers nor loyal citizens in a time of war. Their adversary was a group of lawless evangelists who had formed a church in devotion to the drug’s transformative power: the Brotherhood of Eternal Love.

The poet Allen Ginsberg (left) was one of the performers at the Human Be-In held in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park on 14 January 1967 (Credit: Getty Images)

The Brotherhood had a template for utopia. It was to be found in the final novel, Island, of the grand philosopher of psychedelics, Aldous Huxley. A prominent advocate for the use of psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms, Huxley was a founding member of a pioneering Harvard project led by Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert. Leary and Alpert supervised the Good Friday Experiment at Marsh Chapel in Boston in April 1962, which found that psilocybin profoundly affected the religious experience of nine out of the 10 graduate students.

Huxley’s imagined society is pacifist, cerebral, sexually experimental, spiritual yet anti-clerical

Island had inspired Leary and Alpert to launch the Zihuatanejo Project, a psychedelic training centre under the umbrella of their International Federation for Internal Freedom. The community was located on the coast of south-west Mexico, and it was here that they began writing The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on The Tibetan Book of the Dead. The book was dedicated to Huxley and cites his 1954 essay The Doors of Perception, which explored the hallucinogenic effects of mescaline, a psychedelic substance found in plants indigenous to Mexico. As the Tibetan Book of the Dead had prepared monks for mortality and reincarnation, so The Psychedelic Experience would teach them how to handle the experience of ‘ego death’ and rebirth.

Island life

Island is a utopian counterpoint to Huxley’s dystopian novel Brave New World. It takes place on a fictional island called Pala, named after a town near Mount Palomar in southern California, where Huxley’s friend Edwin Hubble watched the skies and where members of the Brotherhood took acid. The inhabitants of Pala are enriched by their experiences with psychedelic mushrooms, and they create a society that reflects Huxley’s ideals: pacifist, cerebral, sexually experimental, spiritual yet anti-clerical. The novel is a celebration of living in the moment, and, unlike in Brave New World, drugs are a source of enlightenment and compassion rather than pacification.

Huxley requested a high dosage of LSD in his final hours

The year before publication, Huxley’s home in Los Angeles had been destroyed in a fire that left him, in his own words, “a man without possessions and without a past”. He had been diagnosed with laryngeal cancer, and a key theme in the novel is coming to terms with death, which the islanders do with equanimity. Famously, Huxley requested a high dosage of LSD in his final hours – his wife, who administered the injections, described it as “the most serene, most beautiful death”.

Aldous Huxley’s novel Island is seen as a utopian counterpart to Brave New World. It had a huge impact on the Brotherhood of Eternal Love (Credit: Alamy)

The drug had a similarly profound effect on the petty criminals who would become the Brotherhood, two-thirds of whom had already had run-ins with the law. Their founder, John Griggs, was high on heroin when he robbed a Hollywood producer at gunpoint – but after taking LSD for the first time, he renounced violence, apologised and returned the stolen goods. This transformation is not as strange as it may seem: a research experiment in 1962 by Leary’s Harvard Psilocybin Project suggested that recidivism rates could be cut drastically by treating prisoners with psychedelics.

The King of Tonga was even asked to provide the Brotherhood with a home

Initially, the Brotherhood’s aim had been to ‘drop out’ of society and start anew on an island paradise. “To us, the island represented freedom”, says Edward Padilla, an early member of the group. Many of the Brotherhood favoured settling in Hawaii, while a friend of Padilla flew to the remote Pacific island of Micronesia to scout out territory. The British researcher Michael Hollingshead, who first introduced Leary to LSD at the recommendation of Huxley, even spoke to the King of Tonga about providing the Brotherhood with a home.

The Brotherhood hoped to produce LSD in such huge quantities that it would become virtually free (Credit: Alamy)

It was agreed that the Brotherhood would thrive only if they could survive in isolation, and so they began to experiment in communal self-sufficiency. At Modjeska Canyon in Orange County, the group grew their own crops, wove their own clothes, built their own houses, and even learnt how to deliver babies. “Instead of dropping out of society, they created their own version of it”, says Nicholas Schou, author of a book on the Brotherhood. But they were forced to abandon the settlement after it burned down due to a fire at their makeshift church.

Oh, Brother!

Religion was central to the Brotherhood: they referred to themselves as the ‘disciples’, and believed that LSD could ‘heal and reveal’. Schou notes that the group regarded acid as “a sacrament, a window into God itself, a key to unlock ‘the doors of perception’”. Robert Ackerly, who represented the Brotherhood in San Francisco’s hippy Haight-Ashbury district, “felt we were doing God’s work”. A practical reason for registering as a church was to seek religious exemption from prohibition – a strategy pursued by Leary’s own League of Spiritual Discovery.

Acid was taken in such quantities that the Hells’ Angels were asked to run the crèche

In protesting the prohibition, the Human Be-In was fuelled by LSD – acid was taken in such quantities that the Hells’ Angels were asked to run the crèche. Up to 30,000 people heard Leary make a speech in which coined the slogan “Turn on, tune in, drop out”. The Be-In featured poetry from Allen Ginsberg and music from Jefferson Airplane and The Grateful Dead, and inspired a series of imitation events (Love-In, Bed-In).

Timothy Leary’s philosophy of mind expansion through psychedelic drugs made him a messiah of the 1960s counterculture (Credit: Alamy)

The Brotherhood began to distribute – often for free – their own brand of LSD called Orange Sunshine, with funds raised from the smuggling of Afghan hashish, which they brought directly from Kabul and Kandahar, via Karachi, Istanbul, Frankfurt and London. It was an audacious global smuggling operation, with drugs stashed in musical instruments, in a VW camper van, and, in quintessentially Californian style, inside hollowed-out surfboards. Communion with the waves was a core part of the Brotherhood’s spiritual identity – they referred to it as ‘Christ in the Curl’.

Hard comedown

The Brotherhood’s religious inspirations were diverse, from the I Ching to Leary’s Psychedelic Prayers, and strongly favoured the eastern concepts practiced by the islanders of Huxley’s Pala. In Laguna Beach, the group opened a ‘psychedelic emporium’ called Mystic Arts World, in which all the corners were rounded, as stipulated by the Book of Tao. It was in front of this shop that Leary launched his ill-fated bid to be governor of California against Ronald Reagan in 1969, for which John Lennon wrote the campaign song Come Together.

The members of the Brotherhood saw themselves in a quest for human emancipation; law enforcement officials saw it differently (Credit: California Department of Justice)

Seeking privacy, some of the Brotherhood moved inland to a ranch near Idyllwild, to create a couples-only commune led by Leary, who declared that he and Griggs were ‘agents of God’, born to lead ‘a new breed’. Then, at the age of 25, Griggs died of an overdose of psilocybin crystals. The Brotherhood responded by redoubling their commitment, and expanded their operations to produce 10kg of LSD – approximately 100 million doses. According to Michael Randall, a formative member of the Brotherhood, the plan was to drive down the price of LSD through mass production – to distribute “so much Orange Sunshine that it would become virtually free. We had a deep spiritual commitment to what we were doing”.

They dropped 25,000 tabs of acid from a plane onto revellers on the beach below

Brotherhood members, christened the ‘Hippie Mafia’ by the police, used multiple identities to evade detection, but remained socially and politically influential. In 1970, after helping Leary escape a Californian jail, the Brotherhood gave $25,000 to the Black Panthers, who in turn passed it on to the radical left-wing group, the Weather Underground, to smuggle Leary to Algeria and then to Afghanistan. During a three-day ‘happening’ in Laguna Beach – a riotous birthday party for Jesus Christ that began on Christmas Day, 1970 – the Brotherhood dropped 25,000 tabs of acid from a plane onto revellers, in a concerted attempt at communal spiritual revolution.

The Brotherhood featured in the 1972 film Rainbow Bridge, intended as a rejoinder to the dark side of the hippie lifestyle shown in Easy Rider (Credit: Antahkarana Productions)

The group’s celebrity also inspired one of the strangest films ever made, Rainbow Bridge (1972). It features Jimi Hendrix’s final recorded US performance, given exclusively to the Brotherhood at the top of a volcano in Maui, Hawaii. The movie glamourised the group’s activities, which included creating a strain of cannabis called Maui Wowie, but it also revealed their surfboard ruse, to the dismay of some Brotherhood members. The film is a distinctly hippie creation (“Let’s make love…You can’t make love – love is!”), but it was not well-received: one critic described the film as “a ludicrous farrago of pseudo-mystical acid babble devoid of sincerity… the best thing that can be said about Rainbow Bridge is that, after seventy-one minutes, it finishes”.

They’re a bunch of loose cannons on a ship of fools – Owsley Stanley

Not everyone viewed the Brotherhood’s activities as a form of emancipation. In his final annual address to Congress in 1968, President Lyndon Johnson denounced drug distribution, saying “The time has come to stop the sale of slavery to the young”. Owsley Stanley, who made LSD into tablet form for the acid tests of writer Ken Kesey, described the Brotherhood as “loose cannons on a ship of fools”. Richard Alpert, who renamed himself Ram Dass (‘servant of God’) after meeting his guru in India, was wary of the group’s ambition: “They were rebellious and wanted to use psychedelics to challenge the government. They had the tiger by the tail”.

By contrast, Leary believed he was a modern messiah, describing himself as "the wisest man of the 20th Century". He became a divisive figure within the Brotherhood itself, in part because he didn’t share the vision of a surf-rich island utopia. Ultimately, it was Nixon’s war on drugs that undid the Brotherhood, along with the increasing popularity of an alternative ‘unspiritual’ narcotic: cocaine.

Fifty years after the Summer of Love, psychedelics are attracting the attention of the group they first inspired – medical researchers. In the novel Island, a character experiences a ‘good’ death after taking psychedelics, just as Huxley did. Projects at New York University and John Hopkins University are now exploring the effects of psilocybin in palliative care for cancer patients. Huxley’s vision, which has lain dormant for half a century, may yet come to fruition.

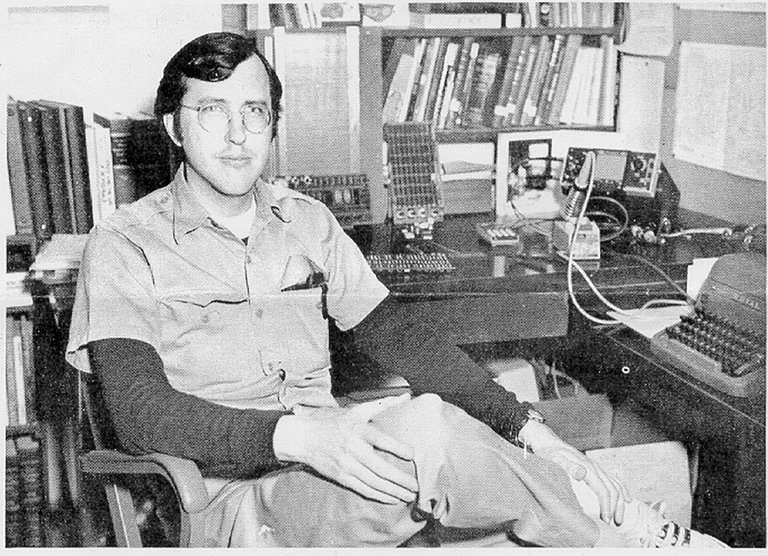

Tim Scully, one of the subjects of Cosmo Feilding Mellen’s documentary “The Sunshine Makers,”

in an undated photo. CreditFilmRise

in an undated photo. CreditFilmRise

NEW YORK TIMES REVIEW, JANUARY 2017

Review: Turning the World On, the LSD Way, in ‘The Sunshine Makers’

THE SUNSHINE MAKERS

Documentary 1h 41m By MANOHLA DARGIS JAN. 19, 2017

The title of the documentary “The Sunshine Makers” — about two trippy American renegades who produced millions of hits of LSD and helped turn on the United States of Acid — sounds like one of those old citrus labels that growers used to slap on wooden crates. With names like Morning Glory, these crates promised a ray of sun in each juicy bite. In 1970, Florida anointed itself the Sunshine State, but this documentary suggests that way out West, where much of this acid was produced, was where the sun shone the brightest.

For Nick Sand and Tim Scully, lysergic acid diethylamide was where it, really everything, was at. Both were in their 20s when they first experimented with psychedelics, an experience they say in the movie indelibly changed each for good and, some might say, bad. A California native, Mr. Scully had been studying at Berkeley before coming under the influence of Owsley Stanley, an intimate of the Grateful Dead and fervent advocate for acid. The more voluble Mr. Sand, a Brooklynite, entered the scene through Millbrook — the estate in upstate New York where Timothy Leary and friends partied for years — eventually going west. (In the early 1960s, Leary helped oversee the Harvard Psilocybin Project, researching LSD.)

Whether together or apart, Mr. Sand and Mr. Scully seemed to be operating on a similar wavelength, and the movie gets a lot of mileage from their sometimes excellent, at times hair-raising, occasionally puckishly funny and altogether wild adventures. At least according to “The Sunshine Makers,” theirs is the story of two young men who found and (arguably) lost their way in the ’60s, a tale that has resonance for the bigger sociopolitical picture. Both Mr. Scully and Mr. Sand saw themselves as missionaries of a type, spreading transcendence one hit at a time. Mr. Sand says that during one early enlightened moment, a voice told him, “Your job on this planet is to make psychedelics and turn on the world.” He obeyed that voice unconditionally.

The director, Cosmo Feilding Mellen, fluidly knits together a lot of information, people and places, sights and sounds, including some faded, pretty far-out archival footage of Mr. Sand and Mr. Scully making acid in labs back in the day. (The editor Nick Packer deserves credit as well.) As Mr. Mellen plaits together these individual histories, he incessantly toggles between past and present. Some of the flashbacks to the ’60s are as familiar as hippie chicks and the corner of Haight and Ashbury, but Mr. Sand and Mr. Scully are true individuals, with delightful quirks and weird tales that keep the material from genericism. (There are several scenes of Mr. Sand practicing yoga in the nude, a lifelong habit that he’s continued into his 70s.)

“The Sunshine Makers” isn’t exactly an advocacy movie, but Mr. Mellen’s sympathies are transparently with his subjects, even if he does check in (humorously and a touch condescendingly) with some of the cops who once chased down Mr. Sand and Mr. Scully. At times, it all seems a bit too, well, sunny, especially given what happened after Mr. Sand and Mr. Scully’s production increased and their stacks of cash grew. (Another documentary, “Orange Sunshine,” focuses on the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, which distributed their acid.) Still, even if you never shake the feeling that there’s more to this story, more darkness and scares, there’s no question that hanging out with Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn on acid has its appeal.

The Sunshine Makers

Not rated. Running time: 1 hour 30 minutes.

Review: Turning the World On, the LSD Way, in ‘The Sunshine Makers’

THE SUNSHINE MAKERS

- Directed by Cosmo Feilding-Mellen

Documentary 1h 41m By MANOHLA DARGIS JAN. 19, 2017

The title of the documentary “The Sunshine Makers” — about two trippy American renegades who produced millions of hits of LSD and helped turn on the United States of Acid — sounds like one of those old citrus labels that growers used to slap on wooden crates. With names like Morning Glory, these crates promised a ray of sun in each juicy bite. In 1970, Florida anointed itself the Sunshine State, but this documentary suggests that way out West, where much of this acid was produced, was where the sun shone the brightest.

For Nick Sand and Tim Scully, lysergic acid diethylamide was where it, really everything, was at. Both were in their 20s when they first experimented with psychedelics, an experience they say in the movie indelibly changed each for good and, some might say, bad. A California native, Mr. Scully had been studying at Berkeley before coming under the influence of Owsley Stanley, an intimate of the Grateful Dead and fervent advocate for acid. The more voluble Mr. Sand, a Brooklynite, entered the scene through Millbrook — the estate in upstate New York where Timothy Leary and friends partied for years — eventually going west. (In the early 1960s, Leary helped oversee the Harvard Psilocybin Project, researching LSD.)

Whether together or apart, Mr. Sand and Mr. Scully seemed to be operating on a similar wavelength, and the movie gets a lot of mileage from their sometimes excellent, at times hair-raising, occasionally puckishly funny and altogether wild adventures. At least according to “The Sunshine Makers,” theirs is the story of two young men who found and (arguably) lost their way in the ’60s, a tale that has resonance for the bigger sociopolitical picture. Both Mr. Scully and Mr. Sand saw themselves as missionaries of a type, spreading transcendence one hit at a time. Mr. Sand says that during one early enlightened moment, a voice told him, “Your job on this planet is to make psychedelics and turn on the world.” He obeyed that voice unconditionally.

The director, Cosmo Feilding Mellen, fluidly knits together a lot of information, people and places, sights and sounds, including some faded, pretty far-out archival footage of Mr. Sand and Mr. Scully making acid in labs back in the day. (The editor Nick Packer deserves credit as well.) As Mr. Mellen plaits together these individual histories, he incessantly toggles between past and present. Some of the flashbacks to the ’60s are as familiar as hippie chicks and the corner of Haight and Ashbury, but Mr. Sand and Mr. Scully are true individuals, with delightful quirks and weird tales that keep the material from genericism. (There are several scenes of Mr. Sand practicing yoga in the nude, a lifelong habit that he’s continued into his 70s.)

“The Sunshine Makers” isn’t exactly an advocacy movie, but Mr. Mellen’s sympathies are transparently with his subjects, even if he does check in (humorously and a touch condescendingly) with some of the cops who once chased down Mr. Sand and Mr. Scully. At times, it all seems a bit too, well, sunny, especially given what happened after Mr. Sand and Mr. Scully’s production increased and their stacks of cash grew. (Another documentary, “Orange Sunshine,” focuses on the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, which distributed their acid.) Still, even if you never shake the feeling that there’s more to this story, more darkness and scares, there’s no question that hanging out with Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn on acid has its appeal.

The Sunshine Makers

- Director Cosmo Feilding-Mellen

- Writer Connie Littlefield

- Stars Nick Sand, Tim Scully

- Running Time 1h 41m

- Genre Documentary

- Movie data powered by IMDb.com

Last updated: Jan 19, 2017

Not rated. Running time: 1 hour 30 minutes.

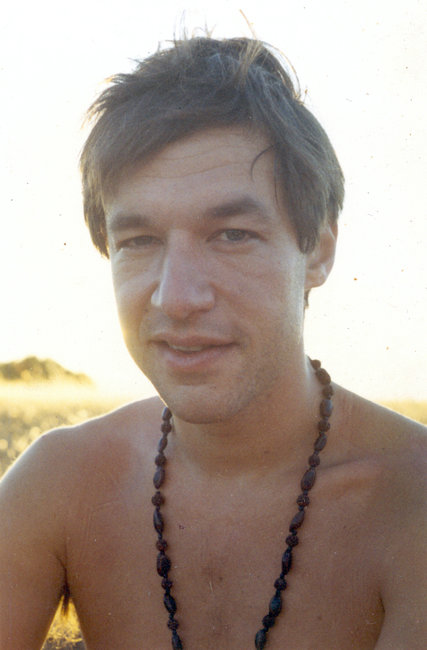

Nick Sand in an undated photo. Credit Nick Sand/FilmRise

Educational Use Only