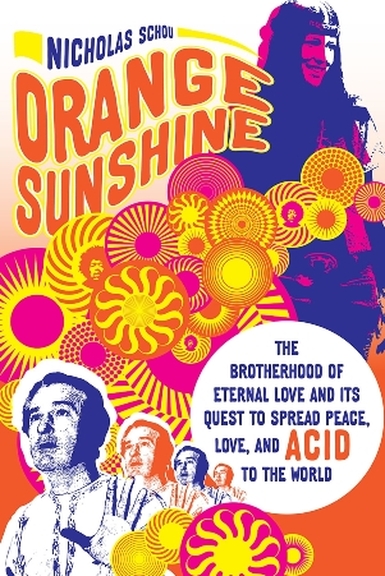

Orange Sunshine

The Book

Orange Sunshine:

The Brotherhood of Eternal Love and Its Quest to Spread Peace, Love & Acid...

by Nick Schou

FACEBOOK https://www.facebook.com/pages/Orange-Sunshine-The-book-by-Nicholas-Schou/366745866648

REVIEW: http://stopthedrugwar.org/chronicle/2010/jul/22/review_orange_sunshine_brotherho

Preview here: http://books.google.com/books?id=OmDd9XKZ6hoC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Orange+Sunshine:+The+Brotherhood+of+Eternal+Love+and+Its+Quest+to+Spread&hl=en&sa=X&ei=gL9gUeT1NsSDjAKpyoDgDA&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAA

The Brotherhood of Eternal Love and Its Quest to Spread Peace, Love & Acid...

by Nick Schou

FACEBOOK https://www.facebook.com/pages/Orange-Sunshine-The-book-by-Nicholas-Schou/366745866648

REVIEW: http://stopthedrugwar.org/chronicle/2010/jul/22/review_orange_sunshine_brotherho

Preview here: http://books.google.com/books?id=OmDd9XKZ6hoC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Orange+Sunshine:+The+Brotherhood+of+Eternal+Love+and+Its+Quest+to+Spread&hl=en&sa=X&ei=gL9gUeT1NsSDjAKpyoDgDA&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAA

Few stories in the annals of American counterculture are as intriguing or dramatic as that of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love.

Dubbed the “Hippie Mafia,” the Brotherhood began in the mid-1960s as a small band of peace-loving, adventure-seeking surfers in Southern California. After discovering LSD, they took to Timothy Leary’s mantra of “Turn on, tune in, and drop out” and resolved to make that vision a reality by becoming the biggest group of acid dealers and hashish smugglers in the nation, and literally providing the fuel for the psychedelic revolution in the process.

Just days after California became the first state in the union to ban LSD, the Brotherhood formed a legally registered church in its headquarters at Mystic Arts World on Pacific Coast Highway in Laguna Beach [sic - Modjeska Canyon], where they sold blankets and other countercultural paraphernalia retrieved through surfing safaris and road trips to exotic locales in Asia and South America. Before long, they also began to sell Afghan hashish, Hawaiian pot (the storied “Maui Wowie”), and eventually Colombian cocaine, much of which the Brotherhood smuggled to California in secret compartments inside surfboards and Volkswagen minibuses driven across the border.

They also befriended Leary himself, enlisting him in the goal of buying a tropical island where they could install the former Harvard philosophy professor and acid prophet as the high priest of an experimental utopia. The Brotherhood’s most legendary contribution to the drug scene was homemade: Orange Sunshine, the group’s nickname for their trademark orange-colored acid tablet that happened to produce an especially powerful trip. Brotherhood foot soldiers passed out handfuls of the tablets to communes, at Grateful Dead concerts, and at love-ins up and down the coast of California and beyond. The Hell’s Angels, Charles Mason and his followers, and the unruly crowd at the infamous Altamont music festival all tripped out on this acid. Jimi Hendrix even appeared in a film starring Brotherhood members and performed a private show for the fugitive band of outlaws on the slope of a Hawaiian volcano.

Journalist Nicholas Schou takes us deep inside the Brotherhood, combining exclusive interviews with both the group’s surviving members as well as the cops who chased them. A wide-sweeping narrative of sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll (and more drugs) that runs from Laguna Beach to Maui to Afghanistan, Orange Sunshine explores how America moved from the era of peace and free love into a darker time of hard drugs and paranoia.

Dubbed the “Hippie Mafia,” the Brotherhood began in the mid-1960s as a small band of peace-loving, adventure-seeking surfers in Southern California. After discovering LSD, they took to Timothy Leary’s mantra of “Turn on, tune in, and drop out” and resolved to make that vision a reality by becoming the biggest group of acid dealers and hashish smugglers in the nation, and literally providing the fuel for the psychedelic revolution in the process.

Just days after California became the first state in the union to ban LSD, the Brotherhood formed a legally registered church in its headquarters at Mystic Arts World on Pacific Coast Highway in Laguna Beach [sic - Modjeska Canyon], where they sold blankets and other countercultural paraphernalia retrieved through surfing safaris and road trips to exotic locales in Asia and South America. Before long, they also began to sell Afghan hashish, Hawaiian pot (the storied “Maui Wowie”), and eventually Colombian cocaine, much of which the Brotherhood smuggled to California in secret compartments inside surfboards and Volkswagen minibuses driven across the border.

They also befriended Leary himself, enlisting him in the goal of buying a tropical island where they could install the former Harvard philosophy professor and acid prophet as the high priest of an experimental utopia. The Brotherhood’s most legendary contribution to the drug scene was homemade: Orange Sunshine, the group’s nickname for their trademark orange-colored acid tablet that happened to produce an especially powerful trip. Brotherhood foot soldiers passed out handfuls of the tablets to communes, at Grateful Dead concerts, and at love-ins up and down the coast of California and beyond. The Hell’s Angels, Charles Mason and his followers, and the unruly crowd at the infamous Altamont music festival all tripped out on this acid. Jimi Hendrix even appeared in a film starring Brotherhood members and performed a private show for the fugitive band of outlaws on the slope of a Hawaiian volcano.

Journalist Nicholas Schou takes us deep inside the Brotherhood, combining exclusive interviews with both the group’s surviving members as well as the cops who chased them. A wide-sweeping narrative of sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll (and more drugs) that runs from Laguna Beach to Maui to Afghanistan, Orange Sunshine explores how America moved from the era of peace and free love into a darker time of hard drugs and paranoia.

From Publishers Weekly

Drug dealers with delusions of grandeur populate this colorful but overwrought history of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, a 1960s-era narcotics ring–cum–hippie church. Influenced by psychedelic prophet Timothy Leary—who called the group's leader, former high school bully John Griggs, the holiest man in America—the California-based Brotherhood styled its cheap, extra-strength Orange Sunshine brand of LSD as a pathway to God. Journalist Schou (Kill the Messenger) takes the spiritual purpose of these psychedelic warriors, along with their solemn acid-dropping sacraments and utopian pipe dreams, rather too seriously. (He likewise inflates their sporadic ventures scoring Mexican marijuana and Afghan hashish into a global smuggling empire.) His narrative quickly devolves into a haphazard picaresque of drug deals, drug busts, overdoses, surfing, rock concerts (Jimi Hendrix does a cameo), orgies, and people living in teepees. Schou sometimes forgets that reading about other people's acid trips—The whole sky took on huge forms of dancing Buddhas and the energy got really bright—is a drag. Still, the mixture of lively freakery and stoned pomposity gives his portrait of countercultural excess an authentic period feel. (Mar.)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. --This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.

From Booklist

The Brotherhood of Eternal Love was a group of 1960s hippie visionaries with a plan. Imagine an America in which LSD is a common source of inspiration and insight for the whole populace, and the pronouncements of Timothy Leary, Ram Dass, and other academic space cowboys are prized philosophical touchstones. Such, more or less, was the group’s goal as producer-distributors of the famous Orange Sunshine LSD that was a part of campus all over America in the late ’60s. At its organizational peak, the Brotherhood funded the Weather Underground and the Black Panthers to successfully break Leary out of prison. Schou interviewed remaining Brotherhood members (who, unlike acid-gobbling pop musicians, seem to have largely retained their memories), gleaning impressive amounts of detail for his discussions of the ins and outs of the era’s drug trade and the moving of vast quantities of marijuana and hashish along with the LSD. Loaded with little-known historical mots, this is an excellent chronicle of a piece of history unlikely to be repeated. --Mike Tribby --This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.

Drug dealers with delusions of grandeur populate this colorful but overwrought history of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, a 1960s-era narcotics ring–cum–hippie church. Influenced by psychedelic prophet Timothy Leary—who called the group's leader, former high school bully John Griggs, the holiest man in America—the California-based Brotherhood styled its cheap, extra-strength Orange Sunshine brand of LSD as a pathway to God. Journalist Schou (Kill the Messenger) takes the spiritual purpose of these psychedelic warriors, along with their solemn acid-dropping sacraments and utopian pipe dreams, rather too seriously. (He likewise inflates their sporadic ventures scoring Mexican marijuana and Afghan hashish into a global smuggling empire.) His narrative quickly devolves into a haphazard picaresque of drug deals, drug busts, overdoses, surfing, rock concerts (Jimi Hendrix does a cameo), orgies, and people living in teepees. Schou sometimes forgets that reading about other people's acid trips—The whole sky took on huge forms of dancing Buddhas and the energy got really bright—is a drag. Still, the mixture of lively freakery and stoned pomposity gives his portrait of countercultural excess an authentic period feel. (Mar.)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. --This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.

From Booklist

The Brotherhood of Eternal Love was a group of 1960s hippie visionaries with a plan. Imagine an America in which LSD is a common source of inspiration and insight for the whole populace, and the pronouncements of Timothy Leary, Ram Dass, and other academic space cowboys are prized philosophical touchstones. Such, more or less, was the group’s goal as producer-distributors of the famous Orange Sunshine LSD that was a part of campus all over America in the late ’60s. At its organizational peak, the Brotherhood funded the Weather Underground and the Black Panthers to successfully break Leary out of prison. Schou interviewed remaining Brotherhood members (who, unlike acid-gobbling pop musicians, seem to have largely retained their memories), gleaning impressive amounts of detail for his discussions of the ins and outs of the era’s drug trade and the moving of vast quantities of marijuana and hashish along with the LSD. Loaded with little-known historical mots, this is an excellent chronicle of a piece of history unlikely to be repeated. --Mike Tribby --This text refers to an out of print or unavailable edition of this title.

By Robert Ackerly -

Nick's book is a Great Read of the High Times and True Adventures of My homeboys since 1957 Fremont Jr. High School. Nick Turned On and Tuned In to the outside fringes of the Original BEL. Most of the interviews were with the known rip off and Snitches. Like Stewart Tendler and Ed May's Book is so full of B.S. We never were a motorcycle club or bullies.

Nick did a miracle good unbiased job getting what he got - but just scratched the surface like i say. From what I saw.

Too Bad I am the only one He could talk to from that Time and I was not hanging With John, Jimmy Dale , Lizard, Johnny Daw, Fasty in 57 cause I just moved there. I was in class with them. I was hanging out With J. C., Tommy and Freddy Tunnel then Lil Billy Erskine joined us. J.C. turned me on to pot in 1960 and LSD in 65 when I came back from Viet Nam after stockpiling Old ammo from Port Chicago California from 62 to Philippines getting ready for the War to 64.

J.C. and Johns Parents moved to California together in the 50s. J.C. was the first one to bring God into the LSD session from what I heard.

J.C. and Tommy T., Lil Bill and Me Had mental telepathy of the highest degree and I still bump Tommy T. hope to see him soon.

Orange Sunshine is a Classic unreal Read but how come they don't arrest JD Green for shooting Peter In the back and moving his body or the old John Birchers who said they burned Mystic Arts World down?

As We march on Occupy Wall street, the federal reserve bank and the Nazi America War Machine that Our fellow Nazi Americans are paying taxes for to their Nazi Masters We can End The Fed Reserve Bank End WAR, POVERTY, TAXES AND 95% OF CRIME.

Prescott Bush was arrested for having Nazi money on his bank. Rockefellers Standard Oil, Exxon and Mobil Oil furnished the chemicals for the Japan and Germans planes and submarines to operate. Since their inception in 1913 They funded every side of every war, created the prohibition, controlled substance act, Depression and rescission by design and their biggest product is War. [...])

Now is the time to stand up for Your rights. The Publisher Weekly, Ted Turners Time Warner, Fox, CBS and all our newspapers and major media are pushing the Nazi War Machine and want to eliminate 95% of the population. This is on their monument Ted Made and in print at their World government, United Nations the Rockefeller and Rothschild built and pay for the home of the OLD New World Order of Nazis. Did you think the Nazis went away? ([...])

Get Hip to the Man - don,t Be lame playing his game -- you're working for the American Nazi man

By John B. Goode on September 20, 2010

I'm surprised at the negative reviews of this book as far as content is concerned. Nick interviewed all persons willing to give input into his book.

Many of the "brothers" are silent today. They are laying low, out of sight and hopefully out of the attention of the agencies who pursued us for so many years.

For many years, late into the seventies, I was stopped and searched by Customs agents whenever I was returning from an international trip. It had the effect of making one desire to be invisible. I don't personally know or remember, "Thumper." He apparently became a protege of John Gale after I left. But much of what he details sounds accurate. The theme I most appreciate about this particular story about the Brotherhood is that (at least in the sixties) we did not exist to make money (although money is nice) but were greatly fueled by a desire to change a world which seemed to be heading for violent chaos or at the very least, a mindless- cookie cutter society. We had become transformed by the taking of LSD and mellowed by the smoking of pot and hashish. This book describes the feeling of those times.

By Michael Pooley (San Diego, Ca) -

I was around during this time and even mentioned in the book. Many people during this time period talked with Nick about the Brotherhood of Eternal Love which was a group of spiritually orientated people and wanted to spread their knowledge of God and Love to others, sharing their experiences and taking groups of people out in the wildness to take LSD and have a spiritual experience, finding Love, compassion for all mankind and taking that home with them and spreading the love they found with others. So this book relates personal experiences and who some of the member were and what they were like. What I found amazing is that we all had a different experience, some better than others, and some of the stories they told I hadn't heard before. The Brotherhood of Eternal Love was a spiritual group and also a major smuggling ring of Hash and Marijuana and producers of some of the strongest LSD. The story tells of the police that wanted to take them down and how the government was dead set against the wisdom from the use of these drugs to get out and used by more people. Nick did a good job with what information was given to him. Many members are still leery of talking about what went on during this time. But we realize it does need to be told so the truth will come out and everyone will know what really happened not just what they (who ever) want you to know. So more books like this one will be published and hopefully it can be told without the ego involved.

Once upon a time there were hippies in Orange County, California.

https://www.erowid.org/library/review/review.php?p=316

To someone like myself who has lived in this ostensibly conservative region for some time, this might already seem like a fairytale. How much more so then to realize that these OC hippies worshipped LSD as a sacrament, distributed unbelievably massive quantities of it, pioneered smuggling hash out of Afghanistan while forming an enormous hash and weed distribution business, counted Timothy Leary as one of their own for a few years and bankrolled his prison breakout by the Weathermen, and were eventually prosecuted out of business by Orange County cops?

The “hippie mafia” in question was the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, and the latest (and by my count only the second) major book to tell their story is Orange Sunshine: The Brotherhood of Eternal Love and Its Quest to Spread Peace, Love, and Acid to the World by OC Weekly investigative reporter Nick Schou. This non-fiction account reads like a late 60s crime thriller, though the crimes in question seem mainly to be quenching an enormous thirst for weed, hash and acid among the young recreational drug-using subcultures of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Though true, it is an amazing tale, especially in Schou’s telling. Schou gets this scene, the humor of it, the foibles, and the sheer legendary stonedness. He also stresses the anecdotal and personal over the larger context, unlike an earlier account of the Brotherhood by Tendler and May. That book, engaging and informative, focused more broadly on LSD in both its cultural milieu and also its main manufacturers. Orange Sunshine focuses almost exclusively on the Brotherhood of Eternal Love itself, with a major exploration of their hash smuggling exploits. Thus the title is a bit of a misnomer.

The Brotherhood was initially a group of violent thugs from the flatlands of Orange County and LA, some of whom were also surfers, who got religion in the form of LSD. Utopian in orientation but street dealers in practice, they figured out how to make a bunch of money from smuggling and distributing their favorite drugs. They didn’t, apparently, ever quite learn how to not bring their work home with them and the tale of their success and dissolution almost seems to suggest that smuggling drugs was the easy part, while just existing while being on so many drugs all the time was tougher. Eventually, carelessness, misadventure, bad luck, and snitches put an end to the Brotherhood. The LSD manufacturing and hash smuggling continued, but that’s another story.

Orange Sunshine mixes together great huge swaths of seemingly disparate Southern California culture. Mean flatland thugs, crazed canyon bikers, stoned coastal surfers, pan-Californian acidheads: the Brotherhood is where these subcultural strands came together. Always seeking a utopian escape, some of its members fled to Maui, where these transplanted pot smugglers turned to big-wave surfing, created Maui Waui, and appeared in the film Rainbow Bridge with Jimi Hendrix, whom they dosed with a DMT-laced joint during his performance. In the great tradition of the Southern Cal/Northern Cal rivalry, the Brotherhood seems simultaneously more heroic, hedonistic, and moronic than the Haight crowd, whom they happily sold weed to and bought Owsley acid from. One of their few NorCal appearances was showing up to dose the Hell’s Angels with acid at Altamont. Sadly, the Brotherhood seemed to have no “house band” counterpart like the Bay Area’s Grateful Dead (one hesitates to guess what this would have sounded like), but its members did include the former drummer of Dick Dale and the Del-Tones. (Dale, the most influential guitarist in the history of surf music, was based in Orange County.)

Schou has a great, almost pulp-entertainment way of telling this story and seems to have put in abundant time interviewing participants of the scene, and the larger-than-life characters he describes come bursting off the page. Most notable is John Griggs, a mean son-of-a-bitch 50s-style jock who changed dramatically after sampling LSD stolen at gunpoint from a Hollywood producer. He became a sort of LSD visionary, leading the Brothers from their criminal ways to, well, way more stoned and peaceful but still criminal ways. Eventually he decided to drop out and formed a communal ranch group in the mountains near Idyllwild, California. It was here that he tragically died of what was reported by onlookers to be an overdose of “synthetic psilocybin” (see Afterword). This sort of horrible comeuppance seemed to be the fate of more than a few of the elite members of the Brotherhood, with accidental deaths, overdoses (including those of children), and busts far too common, though few of the Brotherhood ever served serious time.

But this is not really a cautionary tale, it’s an adventure story, and a ripping one at that. The moral of the story, if there is one, is “Wow, it sure would have been fun to live in Laguna Beach in the 60s!”* It nicely complements other accounts of the cultural history of acid in the 60s such as Storming Heaven and Acid Dreams. Read those for the insightful discussions of the major political shifts and cultural changes of that singular and incredible era, as well as for the equally incredible story of the CIA’s engagement with acid. But read Orange Sunshine for the kicks.

*Actually I did live in Laguna Beach from ‘66 to ‘67, but I was two years old and my parents moved our family, in part, to get away from the drugged-out hippies.

Afterword:

Unfortunately, I find it necessary to write an afterword, as this book is attracting some controversy from within the psychedelic community. The main charge is that the book is error-ridden and inaccurate, the reason being that key participants were not interviewed and some of those who were may have had their own vested interests in providing misleading information. Nick Schou has told me that he made every effort to interview key protagonists including, for example, Nick Sand, who declined several interview requests. Others who denied requests remain anonymous. At the same time, I feel it necessary to point out that Schou did interview a lot of former members of the Brotherhood as well as their family or other hangers-on, thus while it is certainly possible that the book contains some errors, distortions, or omissions, it is impossible to dismiss it as being poorly researched. It clearly and obviously isn’t.

A couple of issues remain. First, there are questions about whether John Griggs really died of an overdose of synthetic psilocybin. I’ve asked Schou and he replied:

“Yes this question always comes up every time someone mentions Griggs’ death. Although it’s not in the book since I only talked to [Brenice] Brennie Smith after I turned in the manuscript, he was there the night Griggs died and confirms that he died of a toxic reaction to a crystallized form of psilocybin as stated in my book. Who knows what else was mixed in with it, but by all accounts, it was poisonous in the extreme in so far as Griggs ingested far too much of it, according to Smith as well as other Brotherhood members who weren’t there but got that story straight from those who were present. Nobody I interviewed for the book who was in the Brotherhood and on the scene when he died have any confusion that this is how he died. It was widely known among the Brotherhood that this psilocybin was making the rounds, see where I mention Ed Padilla mentioning Griggs’ enthusiasm for the stuff the last time he saw Griggs. Some speculate that Griggs choked on his own vomit on the way to the hospital, but Smith says this is not the case and backs up the version in my book.”

Schou also enclosed a death certificate, which listed Griggs’ death as a consequence of “suspected drug intoxication (psilocin)”. This is one of the few known deaths claimed to be caused by an overdose of psilocybin/psilocin. Given that no other fatal ODs from synthetic psilocybin or psilocin have ever been reported, it is possible that this was actually something else, or that the psilocybin was contaminated or adulterated.

Another question is more serious. In October 2009, Schou wrote a story for the OC Weekly on former Brotherhood member Brennie Smith, who had arrived in California in part to be interviewed for a documentary on the Brotherhood, and was arrested on an outstanding warrant.1 Apparently there is suspicion in some quarters that Schou’s publicity of the Brotherhood from his prior OC Weekly stories on the group led to law enforcement’s previously dormant interest in Smith, or that Smith arrived at Schou’s behest. Schou insists that he had no knowledge of Smith’s visit until he arrived, and in fact he gathered information helpful to Smith and shared it with Smith’s defense attorney. Schou’s stance on the ludicrousness of arresting and charging Smith is evident in the follow-up he penned later in October 2009.2 Given Schou’s record of articles and investigative news reporting critical of the War on Drugs and the generally critical bent of the OC Weekly on Orange County law enforcement, the allegation that Schou somehow contributed to Smith’s arrest seems baseless.

Clearly, those who were there and participated are in the best position to evaluate Orange Sunshine’s accuracy, but given the complexity of the Brotherhood, its changes over time, the number of now elderly interviewees Schou talked to, and the fluid nature of memory, this is probably about the best account of a bunch of drug smugglers from 40 years ago that we’re likely to get.

——1) Schou N. “Was Brotherhood Member Brenice Lee Smith a Felonious Monk?“. OC Weekly. Oct 22, 2009.

2) Schou N. “Why is Brenice Lee Smith Still Behind Bars, Awaiting Trial?“. OC Weekly. Oct 28, 2009.

https://www.erowid.org/library/review/review.php?p=316

To someone like myself who has lived in this ostensibly conservative region for some time, this might already seem like a fairytale. How much more so then to realize that these OC hippies worshipped LSD as a sacrament, distributed unbelievably massive quantities of it, pioneered smuggling hash out of Afghanistan while forming an enormous hash and weed distribution business, counted Timothy Leary as one of their own for a few years and bankrolled his prison breakout by the Weathermen, and were eventually prosecuted out of business by Orange County cops?

The “hippie mafia” in question was the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, and the latest (and by my count only the second) major book to tell their story is Orange Sunshine: The Brotherhood of Eternal Love and Its Quest to Spread Peace, Love, and Acid to the World by OC Weekly investigative reporter Nick Schou. This non-fiction account reads like a late 60s crime thriller, though the crimes in question seem mainly to be quenching an enormous thirst for weed, hash and acid among the young recreational drug-using subcultures of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Though true, it is an amazing tale, especially in Schou’s telling. Schou gets this scene, the humor of it, the foibles, and the sheer legendary stonedness. He also stresses the anecdotal and personal over the larger context, unlike an earlier account of the Brotherhood by Tendler and May. That book, engaging and informative, focused more broadly on LSD in both its cultural milieu and also its main manufacturers. Orange Sunshine focuses almost exclusively on the Brotherhood of Eternal Love itself, with a major exploration of their hash smuggling exploits. Thus the title is a bit of a misnomer.

The Brotherhood was initially a group of violent thugs from the flatlands of Orange County and LA, some of whom were also surfers, who got religion in the form of LSD. Utopian in orientation but street dealers in practice, they figured out how to make a bunch of money from smuggling and distributing their favorite drugs. They didn’t, apparently, ever quite learn how to not bring their work home with them and the tale of their success and dissolution almost seems to suggest that smuggling drugs was the easy part, while just existing while being on so many drugs all the time was tougher. Eventually, carelessness, misadventure, bad luck, and snitches put an end to the Brotherhood. The LSD manufacturing and hash smuggling continued, but that’s another story.

Orange Sunshine mixes together great huge swaths of seemingly disparate Southern California culture. Mean flatland thugs, crazed canyon bikers, stoned coastal surfers, pan-Californian acidheads: the Brotherhood is where these subcultural strands came together. Always seeking a utopian escape, some of its members fled to Maui, where these transplanted pot smugglers turned to big-wave surfing, created Maui Waui, and appeared in the film Rainbow Bridge with Jimi Hendrix, whom they dosed with a DMT-laced joint during his performance. In the great tradition of the Southern Cal/Northern Cal rivalry, the Brotherhood seems simultaneously more heroic, hedonistic, and moronic than the Haight crowd, whom they happily sold weed to and bought Owsley acid from. One of their few NorCal appearances was showing up to dose the Hell’s Angels with acid at Altamont. Sadly, the Brotherhood seemed to have no “house band” counterpart like the Bay Area’s Grateful Dead (one hesitates to guess what this would have sounded like), but its members did include the former drummer of Dick Dale and the Del-Tones. (Dale, the most influential guitarist in the history of surf music, was based in Orange County.)

Schou has a great, almost pulp-entertainment way of telling this story and seems to have put in abundant time interviewing participants of the scene, and the larger-than-life characters he describes come bursting off the page. Most notable is John Griggs, a mean son-of-a-bitch 50s-style jock who changed dramatically after sampling LSD stolen at gunpoint from a Hollywood producer. He became a sort of LSD visionary, leading the Brothers from their criminal ways to, well, way more stoned and peaceful but still criminal ways. Eventually he decided to drop out and formed a communal ranch group in the mountains near Idyllwild, California. It was here that he tragically died of what was reported by onlookers to be an overdose of “synthetic psilocybin” (see Afterword). This sort of horrible comeuppance seemed to be the fate of more than a few of the elite members of the Brotherhood, with accidental deaths, overdoses (including those of children), and busts far too common, though few of the Brotherhood ever served serious time.

But this is not really a cautionary tale, it’s an adventure story, and a ripping one at that. The moral of the story, if there is one, is “Wow, it sure would have been fun to live in Laguna Beach in the 60s!”* It nicely complements other accounts of the cultural history of acid in the 60s such as Storming Heaven and Acid Dreams. Read those for the insightful discussions of the major political shifts and cultural changes of that singular and incredible era, as well as for the equally incredible story of the CIA’s engagement with acid. But read Orange Sunshine for the kicks.

*Actually I did live in Laguna Beach from ‘66 to ‘67, but I was two years old and my parents moved our family, in part, to get away from the drugged-out hippies.

Afterword:

Unfortunately, I find it necessary to write an afterword, as this book is attracting some controversy from within the psychedelic community. The main charge is that the book is error-ridden and inaccurate, the reason being that key participants were not interviewed and some of those who were may have had their own vested interests in providing misleading information. Nick Schou has told me that he made every effort to interview key protagonists including, for example, Nick Sand, who declined several interview requests. Others who denied requests remain anonymous. At the same time, I feel it necessary to point out that Schou did interview a lot of former members of the Brotherhood as well as their family or other hangers-on, thus while it is certainly possible that the book contains some errors, distortions, or omissions, it is impossible to dismiss it as being poorly researched. It clearly and obviously isn’t.

A couple of issues remain. First, there are questions about whether John Griggs really died of an overdose of synthetic psilocybin. I’ve asked Schou and he replied:

“Yes this question always comes up every time someone mentions Griggs’ death. Although it’s not in the book since I only talked to [Brenice] Brennie Smith after I turned in the manuscript, he was there the night Griggs died and confirms that he died of a toxic reaction to a crystallized form of psilocybin as stated in my book. Who knows what else was mixed in with it, but by all accounts, it was poisonous in the extreme in so far as Griggs ingested far too much of it, according to Smith as well as other Brotherhood members who weren’t there but got that story straight from those who were present. Nobody I interviewed for the book who was in the Brotherhood and on the scene when he died have any confusion that this is how he died. It was widely known among the Brotherhood that this psilocybin was making the rounds, see where I mention Ed Padilla mentioning Griggs’ enthusiasm for the stuff the last time he saw Griggs. Some speculate that Griggs choked on his own vomit on the way to the hospital, but Smith says this is not the case and backs up the version in my book.”

Schou also enclosed a death certificate, which listed Griggs’ death as a consequence of “suspected drug intoxication (psilocin)”. This is one of the few known deaths claimed to be caused by an overdose of psilocybin/psilocin. Given that no other fatal ODs from synthetic psilocybin or psilocin have ever been reported, it is possible that this was actually something else, or that the psilocybin was contaminated or adulterated.

Another question is more serious. In October 2009, Schou wrote a story for the OC Weekly on former Brotherhood member Brennie Smith, who had arrived in California in part to be interviewed for a documentary on the Brotherhood, and was arrested on an outstanding warrant.1 Apparently there is suspicion in some quarters that Schou’s publicity of the Brotherhood from his prior OC Weekly stories on the group led to law enforcement’s previously dormant interest in Smith, or that Smith arrived at Schou’s behest. Schou insists that he had no knowledge of Smith’s visit until he arrived, and in fact he gathered information helpful to Smith and shared it with Smith’s defense attorney. Schou’s stance on the ludicrousness of arresting and charging Smith is evident in the follow-up he penned later in October 2009.2 Given Schou’s record of articles and investigative news reporting critical of the War on Drugs and the generally critical bent of the OC Weekly on Orange County law enforcement, the allegation that Schou somehow contributed to Smith’s arrest seems baseless.

Clearly, those who were there and participated are in the best position to evaluate Orange Sunshine’s accuracy, but given the complexity of the Brotherhood, its changes over time, the number of now elderly interviewees Schou talked to, and the fluid nature of memory, this is probably about the best account of a bunch of drug smugglers from 40 years ago that we’re likely to get.

——1) Schou N. “Was Brotherhood Member Brenice Lee Smith a Felonious Monk?“. OC Weekly. Oct 22, 2009.

2) Schou N. “Why is Brenice Lee Smith Still Behind Bars, Awaiting Trial?“. OC Weekly. Oct 28, 2009.