Laguna Beach

WET SIDE STORY

Mystic Arts World, Dodge City, 1970 Xmas, Happening, Tim Leary, Surfing

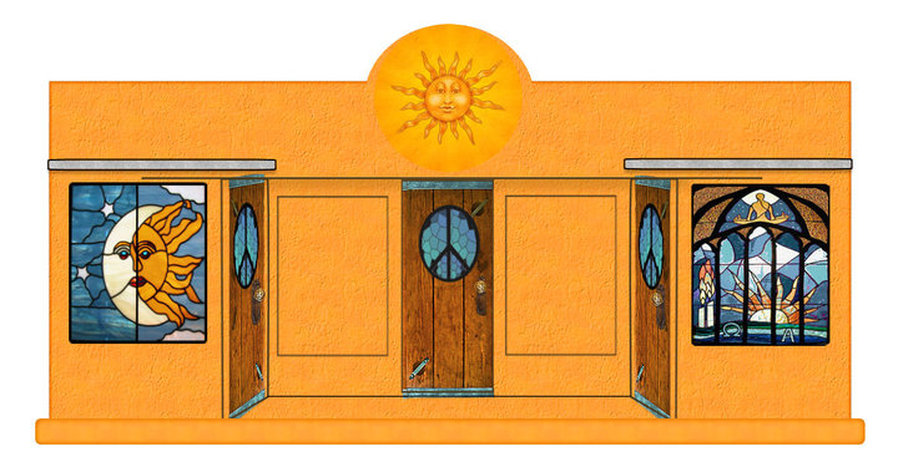

Roger Basset Design

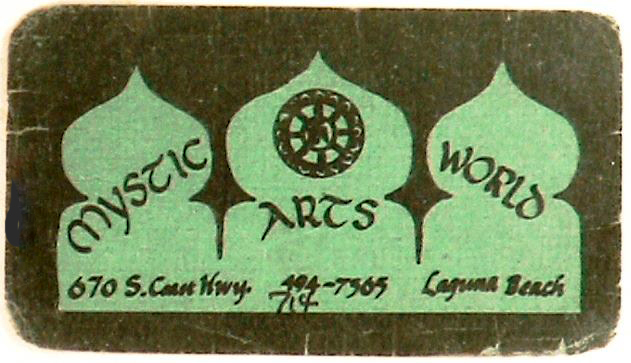

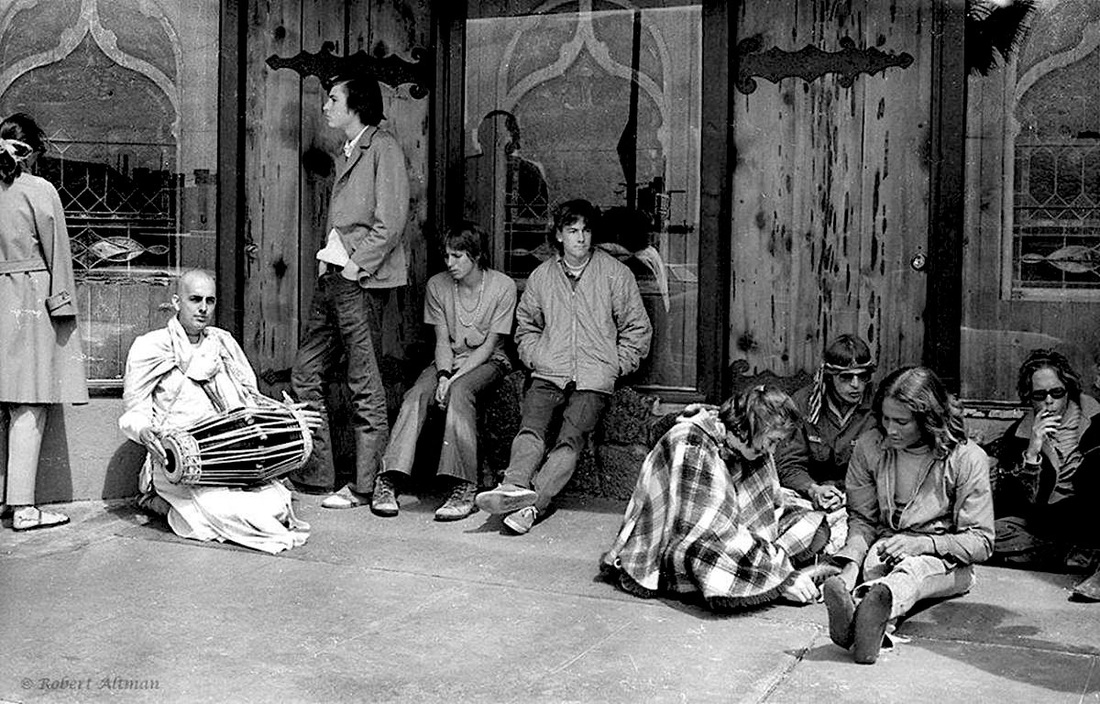

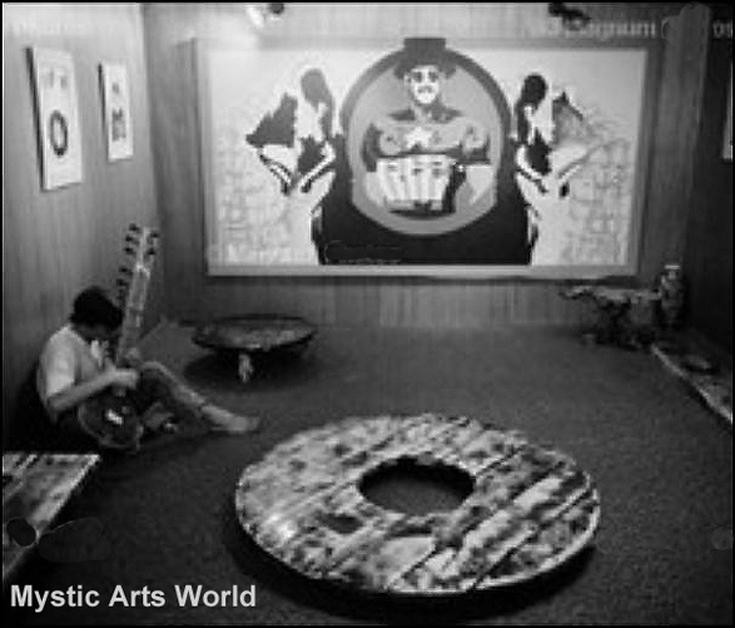

Mystic Arts World (1967-1970), a head shop in Laguna Beach, was ground zero for psychedelic culture in southern California during the late 1960s and early 1970s. It was there that a loosely organized group of artists interested in alternative culture, mystical experience and the transformation of society, “The Mystic Artists”, congregated and exhibited their art. Their artistic expression ranged from Beat assemblage to figuration to psychedelic art. http://stunewslaguna.com/component/content/article/16038-art-exhibit-to-feature-mystic-arts-world-040715

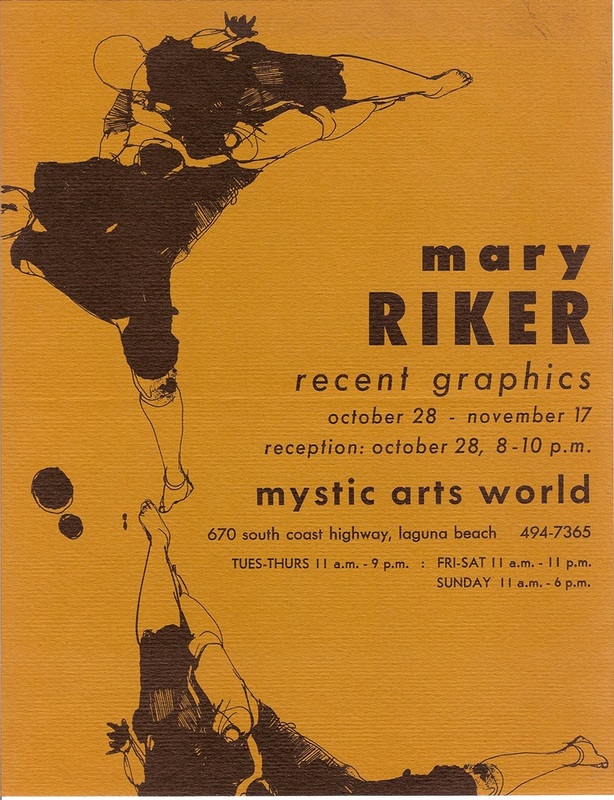

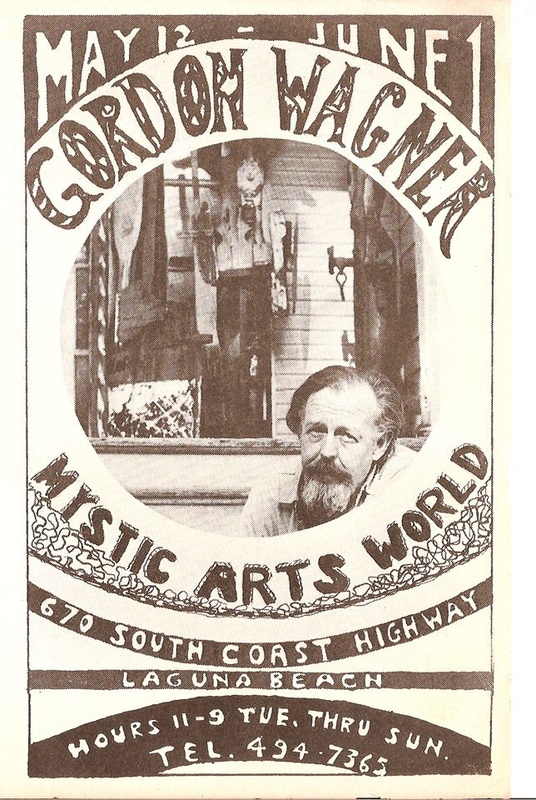

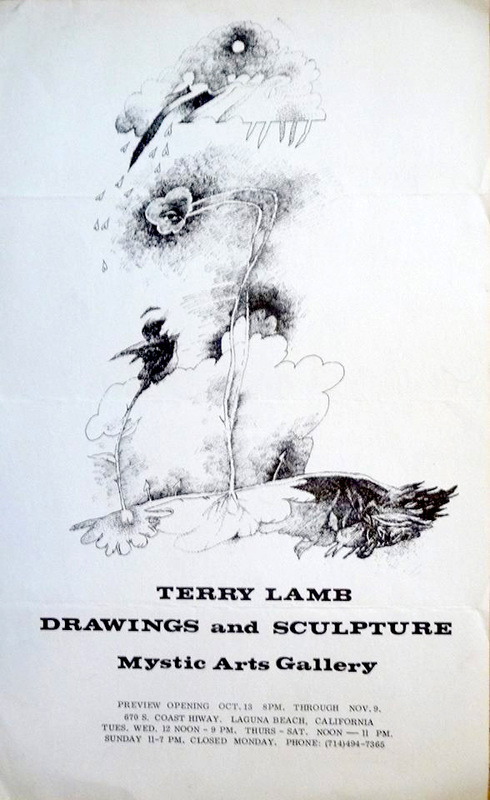

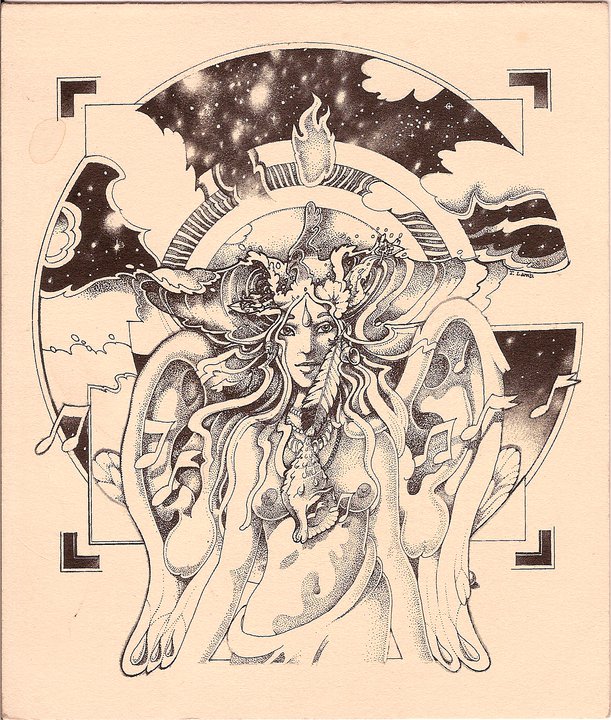

Artists who exhibited at the Mystic Arts World (MAW) included Carol Abrams, Isaac Abrams, Richard Aldcroft, Roger Armstrong, Jan Peters Babcock, Tom Blackwell, Mark Blumenfeld, Robert Ronnie Branaman, Jane Callender, Italo d’Andrea, Paul Darrow, Louis Delsarte, Khigh Alx Dhiegh, Philip Freeman, Ray Friesz, Louis Goodman, Reuben Greenspan, Bill Groves, George Herms, R.L. “Holly” Hollingsworth, Robert Jocko Johnson, Julie Kahn, Steve Kensrue, Karen Kozlow, Terry Lamb, Bob Laney, Ed Lutz, Robert McCarron, Joe Miller, Dwight Morouse, Jim Nussbaum, Harve Parks, Beth Pewther, Noble Richardson, Larry Rink, David Rosen, R.L. Bob Ross, Mary Riker Segal, Gayl Stenlund, Gerd Stern, Jon Stokesbary, Wiktor Sudnik, John Upton, Gordon Wagner, Andy Wing, Dion Wright, and Bob Young. A small section of the exhibition will include the posters and graphics that Bill Ogden did for the Brotherhood and Mystic Arts World.

Artists who exhibited at the Mystic Arts World (MAW) included Carol Abrams, Isaac Abrams, Richard Aldcroft, Roger Armstrong, Jan Peters Babcock, Tom Blackwell, Mark Blumenfeld, Robert Ronnie Branaman, Jane Callender, Italo d’Andrea, Paul Darrow, Louis Delsarte, Khigh Alx Dhiegh, Philip Freeman, Ray Friesz, Louis Goodman, Reuben Greenspan, Bill Groves, George Herms, R.L. “Holly” Hollingsworth, Robert Jocko Johnson, Julie Kahn, Steve Kensrue, Karen Kozlow, Terry Lamb, Bob Laney, Ed Lutz, Robert McCarron, Joe Miller, Dwight Morouse, Jim Nussbaum, Harve Parks, Beth Pewther, Noble Richardson, Larry Rink, David Rosen, R.L. Bob Ross, Mary Riker Segal, Gayl Stenlund, Gerd Stern, Jon Stokesbary, Wiktor Sudnik, John Upton, Gordon Wagner, Andy Wing, Dion Wright, and Bob Young. A small section of the exhibition will include the posters and graphics that Bill Ogden did for the Brotherhood and Mystic Arts World.

Sunshine Juice Bar

"The Brothers settled in Laguna Beach, a small seaside resort thirty miles south of Los Angeles. It was the pure scene, an electric beach community tucked against a semicircle of sandstone hills rising twelve hundred feet above the Pacific. The majestic landscape attracted an artist colony, and the sun and waves brought surfers. John Griggs supplied a lot of LSD for a growing Freaktown where hippies danced barefoot across beaches and mountains murmuring, "Thank you. God." In this exquisite setting the Brothers employed acid as a communal sacrament, hoping eventually to obtain legal permission to expand their consciousness through chemicals in much the same way that the Indians of the Native American Church used peyote. To support their spiritual habit, they opened a storefront in Laguna Beach called Mystic Arts World, which sold health food, books, smoking paraphernalia and other accoutrements of the psychedelic counterculture. The headshop became a meeting place for hippies and freaks of every persuasion, and soon more people wanted to join the fledgling church.

While Mystic Arts provided a steady income, it wasn't enough for the ambitious plans of the Brotherhood. They needed more money to purchase land for their growing membership, so they started dealing drugs—mostly marijuana at first, which they snuck across the border in hundred-pound lots after paying off police officials in

Mexico. Within the next few years the Brotherhood of Eternal Love developed into a sophisticated smuggling and distribution network that stretched around the globe. Huge quantities of hashish were brought in from Afghanistan by Brothers equipped with false ID and crew-cut wigs. They eluded the authorities by zigzagging across oceans and continents in transport outfitted with hollow compartments filled with contraband—unloading at one port, sometimes traveling a short distance overland, then reloading at the next port and substituting yet another phony registration for the vehicle. They also sold LSD obtained from Owsley's lieutenants in Haight-Ashbury.

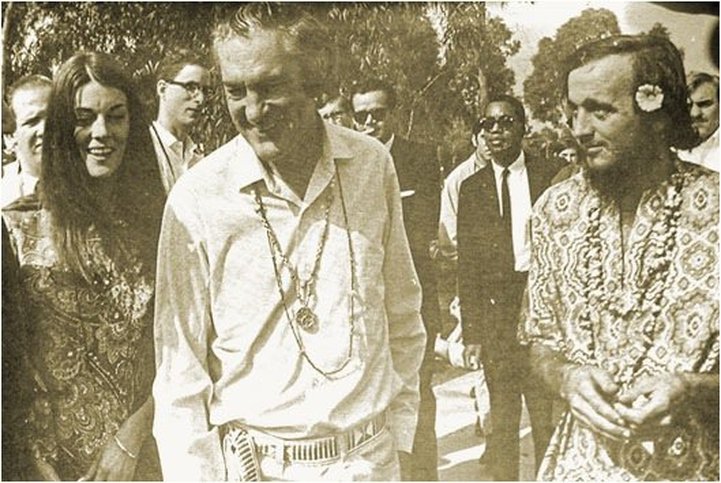

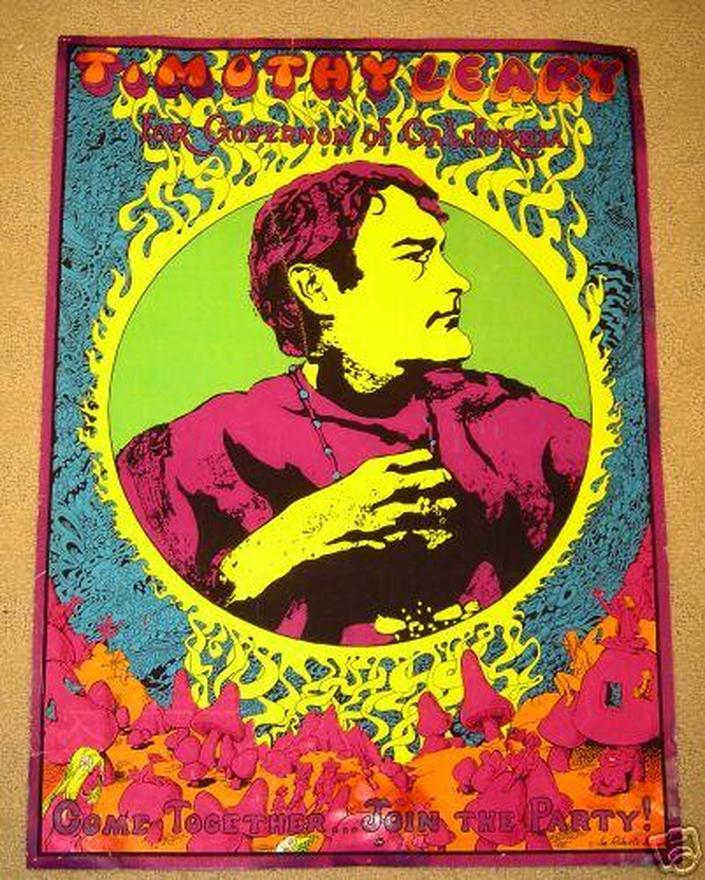

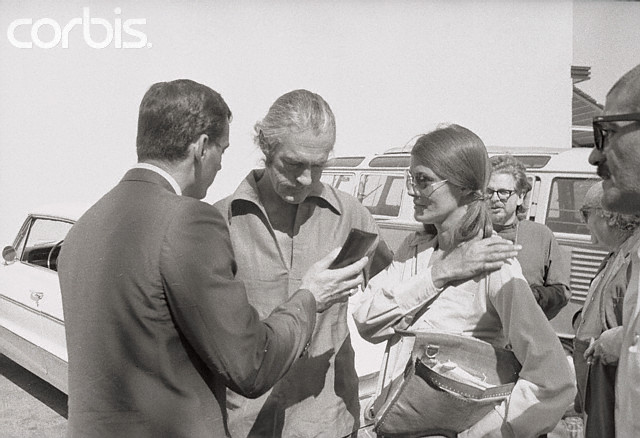

Leary and his new wife, a young ex-model named Rosemary, had a standing invitation from John Griggs to visit Laguna Beach. He was greeted by the Brotherhood like a private heaven-sent prophet, and he acted the part, preaching to the group about love, peace, and enlightenment. Leary enjoyed the adulation as well as the town's mellow atmosphere. He and Rosemary rented a house near the ocean and spent much of their time dropping acid, lolling in the surf, and talking with the hippies on the beach. Leary was very conscious of his role as elder statesman of the town's burgeoning head colony. He tried to stay on good terms with everyone and

never missed a chance to flash his trademark grin when he saw a policeman." --Acid Dreams

While Mystic Arts provided a steady income, it wasn't enough for the ambitious plans of the Brotherhood. They needed more money to purchase land for their growing membership, so they started dealing drugs—mostly marijuana at first, which they snuck across the border in hundred-pound lots after paying off police officials in

Mexico. Within the next few years the Brotherhood of Eternal Love developed into a sophisticated smuggling and distribution network that stretched around the globe. Huge quantities of hashish were brought in from Afghanistan by Brothers equipped with false ID and crew-cut wigs. They eluded the authorities by zigzagging across oceans and continents in transport outfitted with hollow compartments filled with contraband—unloading at one port, sometimes traveling a short distance overland, then reloading at the next port and substituting yet another phony registration for the vehicle. They also sold LSD obtained from Owsley's lieutenants in Haight-Ashbury.

Leary and his new wife, a young ex-model named Rosemary, had a standing invitation from John Griggs to visit Laguna Beach. He was greeted by the Brotherhood like a private heaven-sent prophet, and he acted the part, preaching to the group about love, peace, and enlightenment. Leary enjoyed the adulation as well as the town's mellow atmosphere. He and Rosemary rented a house near the ocean and spent much of their time dropping acid, lolling in the surf, and talking with the hippies on the beach. Leary was very conscious of his role as elder statesman of the town's burgeoning head colony. He tried to stay on good terms with everyone and

never missed a chance to flash his trademark grin when he saw a policeman." --Acid Dreams

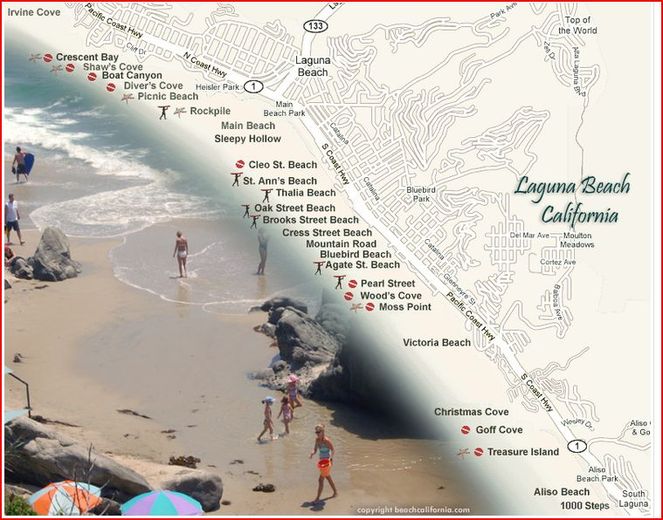

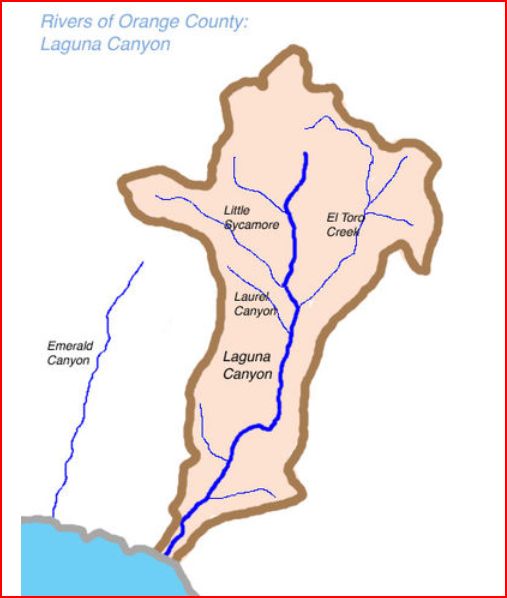

AZ Rainman

Laguna Beach is an artists' colony and resort thirty miles south of Los Angeles. There are only two roads into the town: the Pacific Coast Highway or, from inland, down Laguna Canyon. The town itself, like the Stage of an amphitheatre, sits at the base of a semicircle of sandstone hills rising to 1,200 feet above the Pacific. Amid the bright flowers and clapboard homes the hissing rush of the surf, rolling across the sand eight to twelve feet high, is the major disturber of the peace. The plastic and concrete sprawl of Los Angeles could be on another planet. The peace brought the artists—Laguna has a museum devoted to the works of early Californian painters—and the ocean brought the surfers.

In the early 1960s Laguna was a sleepy little township with the sort of mix to be found in many Californian communities. The American Legion and the Daughters of the American Revolution thrived alongside the artistic community—indeed, the local high school football team was called the Laguna Beach Artists. Once a year on Labor Day, things got a mite out of hand on the 'Walkaround', a fifty-year-old custom in which the passing of summer was mourned, by a walk from bar to bar along the Pacific Coast Highway. Other than that, not much happened in Laguna.

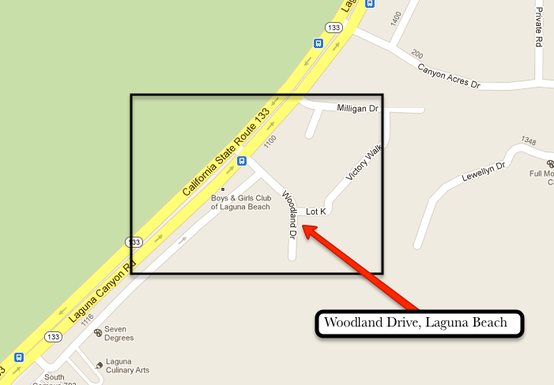

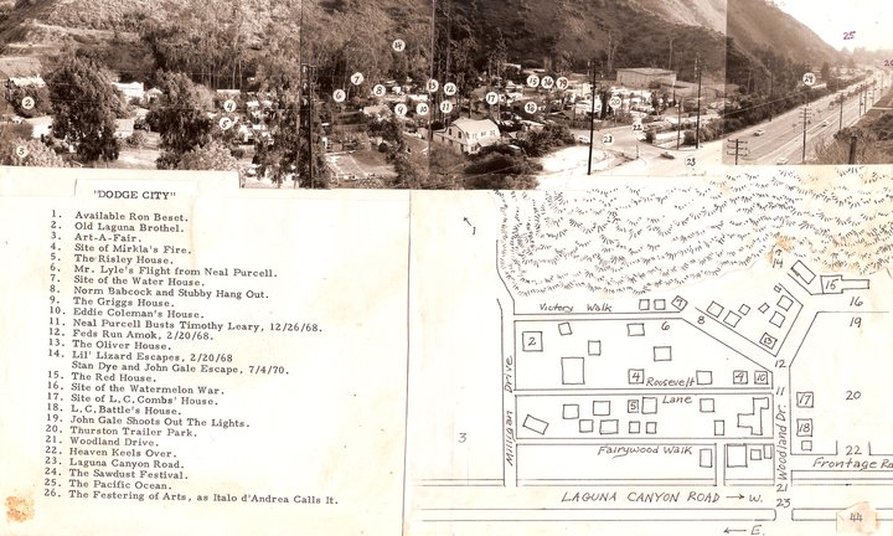

But in the mid-1960s, the number of young surfers was growing and they brought with them other young people eager to live a rude life away from the cities; among them were the Brotherhood. A mile from the beach, a cluster of about fifty houses made up a sub-suburb called Woodland Drive beneath one of the sandstone hills in Laguna Canyon. It was a ramshackle area of gorse and dirt tracks, running down to badly paved streets and a single street light, but it was home for the colony of youngsters. The Brotherhood moved into four white-painted houses.

The scene was painted for a journalist some years later by one of the young men who lived in the Drive: 'I went to school in Hollywood and got into surfing and just like everyone else I wound up in Laguna. Things were happening then, opening up. The chicks were seeing things and there was a lot of grass and there was a vibe that you could make it with love and digging each other... I'd go down to Laguna more and more and finally I just moved into a place on the Canyon with some chicks and a couple of other guys. It was cheap and it was fun. You know the bond, the thing that tied us up together was surfing and dope and balling. We'd get up early in the morning, stay out in the sun all day and somebody always had more grass... Then this cat Farmer John started coming around and he was really into acid. So we did a lot of acid and dug it and Farmer John was putting down a heavy brother-love rap.' Griggs, a charismatic figure, began to enlarge the Brotherhood, drawing people in to create concentric rings which spread out from the central core of Brothers who had moved into Laguna.

The Brotherhood and its apostles were no longer occasional dealers. ne business was now a full-time occupation, financing the way they lived and the opening of the Mystic Arts World Store. At first, there had been odd deals of marijuana tucked inside matchboxes—and, the next moment, consignments of kilos. They arrived in Laguna so often that Lynd for one no longer found anything strange in this new life. 'It was just an everyday occurrence. We would buy kilos of marijuana across the Mexican border and sell them to other Brothers who would turn round and sell them, with the money going to the store. Then there was the LSD sales. Different people would go up to San Francisco which was the place to buy LSD and buy it in quantity to resell in Laguna,' he said. As far as the marijuana was concerned, 'there could be anything from one kilo to as many as 300 to possibly 400 kilos at a time. I had taken kilos most likely on half a dozen occasions, possibly even a dozen occasions to places like San Francisco. Most of the money that was made was turned into the shop. Randall would collect money and Johnny Griggs would collect...'The two men were at the centre of the distribution system for the marijuana. According to Lynd, kilos were bought for $45, sold to Griggs and Randal for $65-$70, who then sold them for $100 or more. The buyers broke down the kilos to smaller dealers selling on the streets. Sales were not confined to the houses up in Woodland Drive. At night, the area round the Taco Bell fast-food stand, close to the Mystic Arts World, and crowded with surfers, beach bums and hippies, buying and trading small deals.

Lynd may have sounded nonchalant about the source of supply in Mexico, but the Brothers worked out a careful system centered on a town near Tijuana, a few miles south of San Diego. The long-haired Brothers may have seemed unlikely company for an officer in the Mexican police, but once a month they met for a quiet chat. There was not much that a policeman missed in a tiny Mexican town. A group of young Americans renting a house, coming and going with battered cars and trucks on the dusty roads in and out of town stood out among the local peasantry and the tourist buses thundering past. But a policeman has to live, even a local police chief. he had arranged their tenancy and offered to watch the house for a few dollars; for $30 a month, the Brothers paid him not to. In return for this outlay, the Brothers could buy their marijuana, hide it in the fenders of their cars and drive across the border without problems. No one seemed to bother them.

Griggs was so excited by the Brothers' successes, he would telephone Leary at Millbrook: 'Hey, Uncle Tim, we've just moved half a ton of grass and we've got some righteous acid.' The calls came in about once a week, but Leary tended to dismiss them, although Jack, his son, now in his teens, decided he would go west to California and have a look. He returned home to Millbrook filled with enthusiasm. One evening, he told his father, Griggs was counting out a stack of $1,000 bills by the light of candies. The air in Griggs' home on Woodland Drive was heavy with incense and the smell of marijuana. Jack Leary leant over, took a banknote and lit it with one of the candles. As a thousand dollars disappeared in a bright flame, black ash and the smell of burning paper, no one batted an eyelid.

But back at Millbrook, Leary was astonished. He called Griggs and offered to repay the $1,000 dollars, but Griggs would have none of it. 'Hey, Uncle Tim, we all wanted to burn a thousand-dollar bill. It was a great thing he did, very enlightening.'

Leary was becoming a frequent visitor to the West Coast as he toured the country lecturing and lobbying. When he decided to visit Laguna with Rosemary, his latest wife, he was greeted like an elder statesman and given conducted tours of the Brothers' achievements. He said: 'They were running the store which was an enormous, beautiful place. Just a group of guys who were pooling all their resources to raise consciousness. They were dedicating their lives to becoming better people. They could see it happening round the country. They were pioneers.'

Hollingshead, the man who had given Leary his first LSD experience, had returned from Britain and joined Leary in Laguna. 'The Brotherhood felt they were leading a new society,' he remembered. 'California was the country of the future. It was as if the culture had entered into them. They were responding. Righteous dealing was a sacrament, with Tim as their guru. I have always found them very gracious people, very honest, very wise—but also very naive. It was the Dead-end Kids who took acid and fell in love with beauty.' The Brothers were making money out of dealing, but Hollingshead said: 'Griggs was not thinking in those terms. He was only thinking of getting the psychedelics on the streets so that people could take them. They were totally committed. They had tremendous determination. They were all very tough; once they were moving dope, they were manic. When the stuff came from Mexico they did this non-stop thing...'

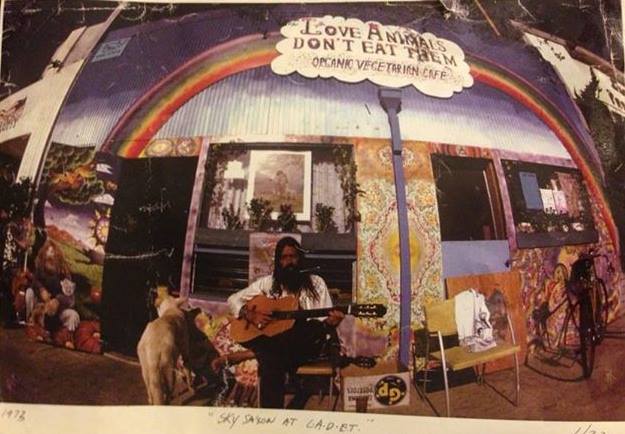

Boney Bananas at the grand opening of 'Love Animals Don't Eat Them' on July 4th, 1972.

In the early 1960s Laguna was a sleepy little township with the sort of mix to be found in many Californian communities. The American Legion and the Daughters of the American Revolution thrived alongside the artistic community—indeed, the local high school football team was called the Laguna Beach Artists. Once a year on Labor Day, things got a mite out of hand on the 'Walkaround', a fifty-year-old custom in which the passing of summer was mourned, by a walk from bar to bar along the Pacific Coast Highway. Other than that, not much happened in Laguna.

But in the mid-1960s, the number of young surfers was growing and they brought with them other young people eager to live a rude life away from the cities; among them were the Brotherhood. A mile from the beach, a cluster of about fifty houses made up a sub-suburb called Woodland Drive beneath one of the sandstone hills in Laguna Canyon. It was a ramshackle area of gorse and dirt tracks, running down to badly paved streets and a single street light, but it was home for the colony of youngsters. The Brotherhood moved into four white-painted houses.

The scene was painted for a journalist some years later by one of the young men who lived in the Drive: 'I went to school in Hollywood and got into surfing and just like everyone else I wound up in Laguna. Things were happening then, opening up. The chicks were seeing things and there was a lot of grass and there was a vibe that you could make it with love and digging each other... I'd go down to Laguna more and more and finally I just moved into a place on the Canyon with some chicks and a couple of other guys. It was cheap and it was fun. You know the bond, the thing that tied us up together was surfing and dope and balling. We'd get up early in the morning, stay out in the sun all day and somebody always had more grass... Then this cat Farmer John started coming around and he was really into acid. So we did a lot of acid and dug it and Farmer John was putting down a heavy brother-love rap.' Griggs, a charismatic figure, began to enlarge the Brotherhood, drawing people in to create concentric rings which spread out from the central core of Brothers who had moved into Laguna.

The Brotherhood and its apostles were no longer occasional dealers. ne business was now a full-time occupation, financing the way they lived and the opening of the Mystic Arts World Store. At first, there had been odd deals of marijuana tucked inside matchboxes—and, the next moment, consignments of kilos. They arrived in Laguna so often that Lynd for one no longer found anything strange in this new life. 'It was just an everyday occurrence. We would buy kilos of marijuana across the Mexican border and sell them to other Brothers who would turn round and sell them, with the money going to the store. Then there was the LSD sales. Different people would go up to San Francisco which was the place to buy LSD and buy it in quantity to resell in Laguna,' he said. As far as the marijuana was concerned, 'there could be anything from one kilo to as many as 300 to possibly 400 kilos at a time. I had taken kilos most likely on half a dozen occasions, possibly even a dozen occasions to places like San Francisco. Most of the money that was made was turned into the shop. Randall would collect money and Johnny Griggs would collect...'The two men were at the centre of the distribution system for the marijuana. According to Lynd, kilos were bought for $45, sold to Griggs and Randal for $65-$70, who then sold them for $100 or more. The buyers broke down the kilos to smaller dealers selling on the streets. Sales were not confined to the houses up in Woodland Drive. At night, the area round the Taco Bell fast-food stand, close to the Mystic Arts World, and crowded with surfers, beach bums and hippies, buying and trading small deals.

Lynd may have sounded nonchalant about the source of supply in Mexico, but the Brothers worked out a careful system centered on a town near Tijuana, a few miles south of San Diego. The long-haired Brothers may have seemed unlikely company for an officer in the Mexican police, but once a month they met for a quiet chat. There was not much that a policeman missed in a tiny Mexican town. A group of young Americans renting a house, coming and going with battered cars and trucks on the dusty roads in and out of town stood out among the local peasantry and the tourist buses thundering past. But a policeman has to live, even a local police chief. he had arranged their tenancy and offered to watch the house for a few dollars; for $30 a month, the Brothers paid him not to. In return for this outlay, the Brothers could buy their marijuana, hide it in the fenders of their cars and drive across the border without problems. No one seemed to bother them.

Griggs was so excited by the Brothers' successes, he would telephone Leary at Millbrook: 'Hey, Uncle Tim, we've just moved half a ton of grass and we've got some righteous acid.' The calls came in about once a week, but Leary tended to dismiss them, although Jack, his son, now in his teens, decided he would go west to California and have a look. He returned home to Millbrook filled with enthusiasm. One evening, he told his father, Griggs was counting out a stack of $1,000 bills by the light of candies. The air in Griggs' home on Woodland Drive was heavy with incense and the smell of marijuana. Jack Leary leant over, took a banknote and lit it with one of the candles. As a thousand dollars disappeared in a bright flame, black ash and the smell of burning paper, no one batted an eyelid.

But back at Millbrook, Leary was astonished. He called Griggs and offered to repay the $1,000 dollars, but Griggs would have none of it. 'Hey, Uncle Tim, we all wanted to burn a thousand-dollar bill. It was a great thing he did, very enlightening.'

Leary was becoming a frequent visitor to the West Coast as he toured the country lecturing and lobbying. When he decided to visit Laguna with Rosemary, his latest wife, he was greeted like an elder statesman and given conducted tours of the Brothers' achievements. He said: 'They were running the store which was an enormous, beautiful place. Just a group of guys who were pooling all their resources to raise consciousness. They were dedicating their lives to becoming better people. They could see it happening round the country. They were pioneers.'

Hollingshead, the man who had given Leary his first LSD experience, had returned from Britain and joined Leary in Laguna. 'The Brotherhood felt they were leading a new society,' he remembered. 'California was the country of the future. It was as if the culture had entered into them. They were responding. Righteous dealing was a sacrament, with Tim as their guru. I have always found them very gracious people, very honest, very wise—but also very naive. It was the Dead-end Kids who took acid and fell in love with beauty.' The Brothers were making money out of dealing, but Hollingshead said: 'Griggs was not thinking in those terms. He was only thinking of getting the psychedelics on the streets so that people could take them. They were totally committed. They had tremendous determination. They were all very tough; once they were moving dope, they were manic. When the stuff came from Mexico they did this non-stop thing...'

Boney Bananas at the grand opening of 'Love Animals Don't Eat Them' on July 4th, 1972.

|

|

|

The Greeter; Flashbacks

Dude, Spare Me the Trip Reports

1960s: We buzzed up and down Hwy 1 in our white Renault Caravelle Cabrio, the hot car in Paris at the time. Other times we rode in our boyfriends' surf wagons. I remember the foggy drives through Laguna Canyon, survivable only by intuitive second-sight. Because I had relatives there, I was already familiar with the twisting roads. I also have fond memories of the 'Jonah in the Whale' Cave at 1000 Steps Beach. When you sat in it, it felt like being in the belly of a whale. We also loved the 7 sea caves in La Jolla. We partied in Los Trancos, a historic district of 1930s style houses and in the cliff villas.

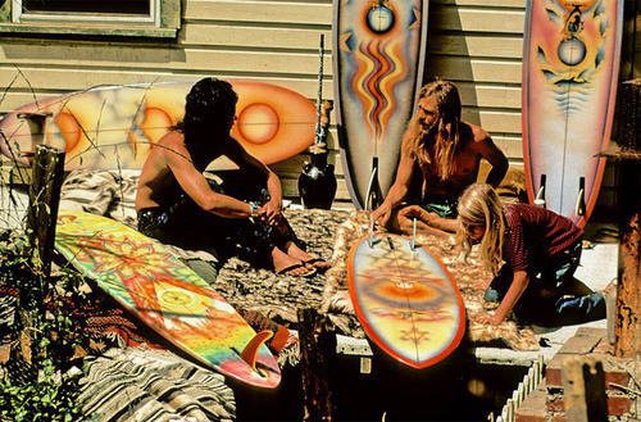

Maybe there would be a Leary sighting. The twist in BEL's philosophy was that they smuggled hash to pay to make more acid they virtually gave away. They believed their panacea would change the world. Or, at least, that was the story. First they got their legs wet, smuggling pot from Sinaloa, Mexico in rainbow surfboards, then they went to Afghanistan for hash.

BEL's stained-glass shopfront pleasure palace cum headshop, "Mystic Arts World", became a hippie Mecca that stalled traffic on Hwy. 101. You never saw so many beads in your life. Tim Leary declared his candidacy for California Governor from there in 1969. Being young and naive at the time, I had no idea we were partying with what would later be called "the hippie Mafia" by Rolling Stone magazine. That is, until my cousin married one of them.

The Original "Mystic Arts World" is arguably one of the first Organic Spiritual Centers, offering vegetarian health foods and herbs, incense, art, jewelry, beads, a mystic book store, secret stash rooms, and Holy Sacraments with a private Meditation Temple for members of the BEL.

Maybe there would be a Leary sighting. The twist in BEL's philosophy was that they smuggled hash to pay to make more acid they virtually gave away. They believed their panacea would change the world. Or, at least, that was the story. First they got their legs wet, smuggling pot from Sinaloa, Mexico in rainbow surfboards, then they went to Afghanistan for hash.

BEL's stained-glass shopfront pleasure palace cum headshop, "Mystic Arts World", became a hippie Mecca that stalled traffic on Hwy. 101. You never saw so many beads in your life. Tim Leary declared his candidacy for California Governor from there in 1969. Being young and naive at the time, I had no idea we were partying with what would later be called "the hippie Mafia" by Rolling Stone magazine. That is, until my cousin married one of them.

The Original "Mystic Arts World" is arguably one of the first Organic Spiritual Centers, offering vegetarian health foods and herbs, incense, art, jewelry, beads, a mystic book store, secret stash rooms, and Holy Sacraments with a private Meditation Temple for members of the BEL.

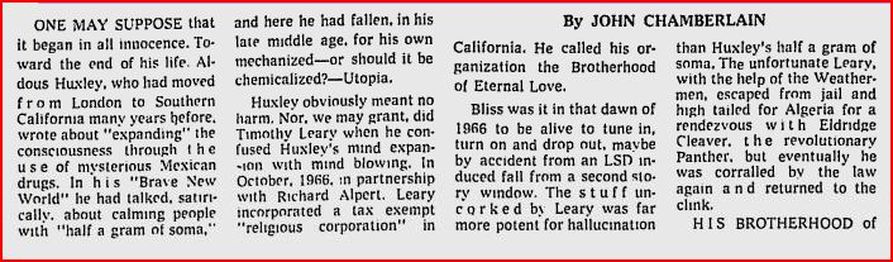

The Second Psychedelic Revolution Part Two: Alexander ‘Sasha’ Shulgin, The Psychedelic Godfather

by James Oroc

At a testimonial dinner for the Shulgins in 2010 at the MAPS conference in San Jose, CA, the underground chemist Nick Sand (who had only recently been released from jail), and who (along with Tim Scully, who was Owsley’s chemist) is often credited with the ‘invention’ of Orange Sunshine LSD, revealed that in 1966, after LSD had been made illegal in California thanks to the newly elected Governor Ronald Reagan, the precursors required for creating LSD under the methods of the day dried up, and for a short time LSD actually disappeared and much like would happen some twenty four years later in 2000, it appeared as if there could be ‘an End to Acid’.

According to the historical record, Sand and Scully then started manufacturing DOM (street name STP), an extraordinarily powerful psychedelic phenethylamine invented by Shulgin in 1964. Five thousand ‘doses’ of this new compound were given away at the first Human Be-In in San Francisco (Jan 14th, 1967) in an effort to promote the new drug as a ‘replacement’ to LSD, but unfortunately they (Sand and Scully) had apparently developed a tolerance to DOM, and reputedly made the dosages too high. This combined with the fact that the onset of DOM was much slower than LSD, with many people reportedly making the mistake of taking a second hit after an hour or so with little effect, caused numerous users to overdose and sent scores of ‘tripping hippies’ to the city’s emergency rooms. The press then further demonized LSD by reporting that this was the compound responsible.

Perhaps due to the aftermath of the Human Be-In debacle, Nick Sand and Tim Scully were then given a formula for a new method of manufacturing LSD that got around the constraints of the old method; they were told that it was from a ‘friend’, an ally who believed in what they were doing, but couldn’t be revealed at that time. At the MAPS testimonial dinner for the Shulgins in 2010, in a startling revelation whose importance somewhat slipped by most of the gathered audience and as far as I know has never been reported, Nick Sand identified that mysterious ‘friend’ as Sasha.

Assuming this is true—and obviously Nick Sand would have no reason to make up a story like that—this means that along with popularizing MDMA, and inventing literally hundreds of psychedelic and empathogenic compounds that have surfaced with increasing regularity in the 21st century, Alexander Shulgin was also the inventor of Orange Sunshine LSD, which was by far the most commonly manufactured LSD from the late 1960’s onward (Orange Sunshine is estimated to have been over 75% of the worlds LSD). Or to put it another way, while Albert Hoffman invented LSD, it can now be said that it was thanks to Sasha (and the bravery of Nick Sand, Tim Scully, and the Brotherhood of Eternal Love) that it was available from 1967 on!

http://www.rigorousintuition.ca/board2/viewtopic.php?t=32959&p=538099

by James Oroc

At a testimonial dinner for the Shulgins in 2010 at the MAPS conference in San Jose, CA, the underground chemist Nick Sand (who had only recently been released from jail), and who (along with Tim Scully, who was Owsley’s chemist) is often credited with the ‘invention’ of Orange Sunshine LSD, revealed that in 1966, after LSD had been made illegal in California thanks to the newly elected Governor Ronald Reagan, the precursors required for creating LSD under the methods of the day dried up, and for a short time LSD actually disappeared and much like would happen some twenty four years later in 2000, it appeared as if there could be ‘an End to Acid’.

According to the historical record, Sand and Scully then started manufacturing DOM (street name STP), an extraordinarily powerful psychedelic phenethylamine invented by Shulgin in 1964. Five thousand ‘doses’ of this new compound were given away at the first Human Be-In in San Francisco (Jan 14th, 1967) in an effort to promote the new drug as a ‘replacement’ to LSD, but unfortunately they (Sand and Scully) had apparently developed a tolerance to DOM, and reputedly made the dosages too high. This combined with the fact that the onset of DOM was much slower than LSD, with many people reportedly making the mistake of taking a second hit after an hour or so with little effect, caused numerous users to overdose and sent scores of ‘tripping hippies’ to the city’s emergency rooms. The press then further demonized LSD by reporting that this was the compound responsible.

Perhaps due to the aftermath of the Human Be-In debacle, Nick Sand and Tim Scully were then given a formula for a new method of manufacturing LSD that got around the constraints of the old method; they were told that it was from a ‘friend’, an ally who believed in what they were doing, but couldn’t be revealed at that time. At the MAPS testimonial dinner for the Shulgins in 2010, in a startling revelation whose importance somewhat slipped by most of the gathered audience and as far as I know has never been reported, Nick Sand identified that mysterious ‘friend’ as Sasha.

Assuming this is true—and obviously Nick Sand would have no reason to make up a story like that—this means that along with popularizing MDMA, and inventing literally hundreds of psychedelic and empathogenic compounds that have surfaced with increasing regularity in the 21st century, Alexander Shulgin was also the inventor of Orange Sunshine LSD, which was by far the most commonly manufactured LSD from the late 1960’s onward (Orange Sunshine is estimated to have been over 75% of the worlds LSD). Or to put it another way, while Albert Hoffman invented LSD, it can now be said that it was thanks to Sasha (and the bravery of Nick Sand, Tim Scully, and the Brotherhood of Eternal Love) that it was available from 1967 on!

http://www.rigorousintuition.ca/board2/viewtopic.php?t=32959&p=538099

Dodge City

Mystic Arts World, Headshop / Art Gallery

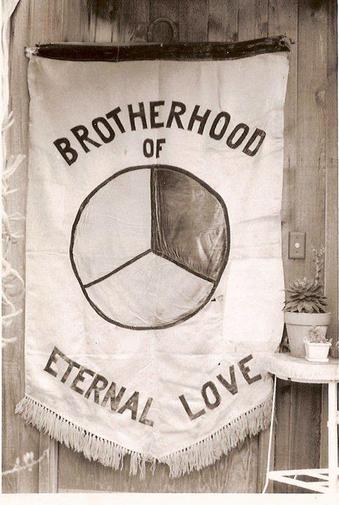

The year was 1969, and Laguna Beach, once the sleepy refuge of surfers, artists, and bohemians of little consequence, was a center of counterculture foment after a band of outlaws and outcasts went up a mountain with LSD and came down as messengers of love, peace and the transformational qualities of acid and hash. They called themselves the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, and Mystic Arts World was their public face, a hippie hangout where vegetarianism, Buddhism, meditation and all sorts of Aquarian ideals spread like gospel.

http://slake.la/features/the-pirate-of-penance

http://slake.la/features/the-pirate-of-penance

Turn Off Your Mind, Relax and Float Downstream..."

TERRY LAMB

http://www.terrylambart.com/

http://www.terrylambart.com/

http://www.druglibrary.net/schaffer/lsd/books/bel3.htm

The Mystic Arts World Store was opposite a Mexican fast-food stand on South Laguna Beach. At the front it sold the sort of things to be found in a thousand similar stores that were sprouting up across the America of 1966 and 1967—home-made clothes, natural foods, leatherware, brass, tapestries, pipes and papers for marijuana smoking: another 'head shop', a sort of frontier store for America's newest pioneers, the hippies; a corner shop for the colony of young people moving into Laguna Beach, south of Los Angeles, to enjoy a 'Haight-Ashbury on sea'.

But the real business of Mystic Arts lay at the back in the meditation room. The floor was covered from wall to wall by foam rubber overlaid with thick carpeting, making visitors feel as though they were walking on a huge, luxurious bed. At one end, a small waterfall tumbled into an indoor rock garden. The sound was soft and rhythmic, lulling. In another corner stood a water pipe. Scatter cushions had been left here and there for customers, who removed their shoes before entering, to loll at their ease. A group of young men in their twenties might be sitting round at the beginning of an LSD session: their hair was long; they wore patched jeans and loose shirts, embroidered waistcoats over painted T-shirts and single strings of thick, crude beads. Some had the deep sunburn that you find in this part of California on surfers, where the heat of the sun has burnt into the skin, magnified by the sea-water, and left a rich tan. Others had the thick-set, hard-muscled build of mechanics.

They were men with a cause, yet theirs was not quite the burning ardor of the radicals elsewhere in the country, streaming across the campuses towards the administration blocks and screaming against betrayal, grappling with the police as they denounced L.B.J. and vowing they would never fight in Vietnam. Theirs was another kind of fervor: there was no violence, just the unswerving confidence of missionaries going about their work.

The meditation room was, on occasion, the private chapel of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, a legally incorporated religious charity. At other times it was the front office of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, drug dealers extraordinary. The essence of the Brotherhood might well be summed up in Owsley's 'chemistry is theology'.

The man to watch at the LSD sessions was a short, stocky character wearing a Hopi Indian headband and flowing green Eastern trousers and shirt. John Griggs, dark and intense with bright blue eyes, was the founding figure of the Brotherhood: a man who had discovered LSD in dramatic circumstances.

At the time, Griggs, approaching his middle twenties, was the leader of a marijuana-smoking south Los Angeles motorcycle gang, preying on supermarkets. Largely unschooled, Griggs was a wandering adventurer who had earned the name of 'Farmer John' after disappearing into the Californian mountains to live as a trapper. He rode with his pack along the freeways and highways that criss-crossed Los Angeles in search of fresh excitement. On a summer night he led his gang through Hollywood towards Beverly Hills and Mulholland Drive. According to the grapevine, a well-known Hollywood film producer up there kept a cache of pure LSD in his refrigerator. Griggs and the gang decided it was time they tried this LSD stuff everyone was talking about.

They burst in on the producer during a dinner party. All the guests froze as the gang, armed with guns and knives, came out of the darkness... but all they wanted was the LSD, and they took it. The host was so relieved that he rushed out to the driveway as they started up their motorcycles and cried after them: 'Have a great trip, boys. Jesus, I thought it was something serious.'

The gang roared out of Los Angeles towards the vast, high acres of Joshua Tree National Park beyond the city. They climbed higher and higher into the hills among the yucca trees until they were above Palm Springs and, at midnight, they came to a halt. Motorcycles parked in a group, they stood round in the clear, sharp mountain air and shared out the LSD, made by Sandoz. Each man swallowed the equivalent of 1,000 micrograms, four times a normal dose, and wandered off to await the result. It was cold and the yuccas with their twisted stems and shrouds of dead leaves cast fantastic shapes in the gloom.

As the sun burst across the sky at dawn, hours later, Griggs threw his gun into the dry scrub and shouted: 'This is it. This is it.' The gang regrouped round their motorbikes, shaken and overwhelmed. All had thrown away their weapons. They started home for Anaheim, a flat Los Angeles suburb of pale-coloured houses, and what was to be a new life.

Griggs was the proselytizer, the moving spirit. He talked to old schoolfriends like Glen Lynd and Calvin Delaney. Lynd had already tried marijuana and now took the LSD Griggs passed on to him. Like Griggs, Lynd was in his middle twenties and something of a drifter. The group that began to assemble totalled nine. Most of the young men, all in their early or middle twenties, came from Anaheim. Michael Randall was from Long Beach, although he had attended Anaheim Western High School. He started smoking marijuana in 1963 but remained on the edge of the group, since, he was finishing a course in business administration at California State College.

At first, the group did little more than meet at the weekends to try out the psychedelics, but Griggs had wider visions. He urged the others to move with him out of Los Angeles, east to Modjeska Canyon, in the countryside beyond the city. The group shared a couple of houses, feeling, like Alpert and Leary had felt at Harvard, that they had 'something wonderful in common'. Those who had jobs continued to work—Russ Harrigan for example was a longshoreman—but all now began a little drug dealing as well. Lynd and Harrigan went down to San Pedro with the odd kilo of marijuana brought back from trips to Mexico, and all the group sold LSD from San Francisco to visitors to Modjeska Canyon. Several of them enrolled in research programs at the University of California, Los Angeles, in order to continue using the psychedelics for free.

But on Wednesday nights they came together to talk about their futures. Lynd said later: 'There was hopeful thought of buying land... the purpose was to buy it so people could live on it. We could farm it or whatever.' Plans began to form round the notion. Lynd had heard Leary lecturing and had been impressed. Griggs went east to meet him at Millbrook. Leary was taken with him: 'an incredible genius' was how he described Griggs; 'although unschooled and unlettered he was an impressive person. He had this charisma, energy, that sparkle in his eye. He was good-natured, surfing the energy waves with a smile on his face.' As far as Griggs was concerned, Leary was his guru, one with some useful practical ideas.

In the summer of 1966 when Griggs went to Millbrook, Leary was working on his plans for the formation of the League of Spiritual Discovery. Griggs and his friends seemed to have a good thing going out there in the West, so why not set up something similar? The new psychedelic religion was not something all-embracing and spiritually omnipotent. There was no Pope to set out the prescribed dogma. This religion was about a new kind of spiritual freedom which you found for yourself. The basic tenets of the League included: 'enthusiastic acceptance of the sacramental method by the young... a recognition that the search for God is a private affair... the rituals spring from experiences of the small worship group... the leaven works underground... friends initiate, teach, prepare and guide...'

Ten days after California banned LSD in October 1966, Lynd, his wife and a friend walked into the offices of a Los Angeles attorney on Sunset Boulevard and signed the papers incorporating the Brotherhood; Lynd was the only Brother who did not have a criminal record, so he was designated to organize the incorporation. According to the legal papers, the Brotherhood, tax exempt, was dedicated 'to bring to the world a greater awareness of God through the teachings of Jesus Christ, Rama-Krishnam Babaji, Paramahansa Yogananda, Mahatma Gandhi and all true prophets and apostles of God'. Was there a hint of Leary's influence in this list? Griggs had recently returned from a trip to the East, and the Brothers were largely 'unschooled'.

To achieve its ends, the Brotherhood intended to 'buy, manage and own and hold real and personal property necessary and proper for a place of public worship and carry on educational and charitable work'. Was there an echo of the League's tenets in article 4-D which read: 'We believe in the sacred right of each individual to commune with God in spirit and in truth as it is empirically revealed to him'? This was 'a recognition that the search for God is a private matter', written another way.

Lynd said years later: 'Well, it was John Griggs' main idea to incorporate because he had talked to Leary, and it was possible to incorporate to become tax-exempt as far as land goes and, if and when marijuana ever becomes legal, become tax-exempt on marijuana.' There were no fixed rules for joining; no name signing or ritual. But there was one basic rule among the Brothers—they believed in taking as much of the psychedelics as possible, the largest doses of LSD they could buy. The articles of association did not explain how the Brotherhood intended to buy its land or establish its place of worship. You cannot really tell a lawyer or the State of California that you intend to raise capital by breaking the law—by massive dealing in drugs.

Laguna Beach is an artists' colony and resort thirty miles south of Los Angeles. There are only two roads into the town: the Pacific Coast Highway or, from inland, down Laguna Canyon. The town itself, like the Stage of an amphitheatre, sits at the base of a semicircle of sandstone hills rising to 1,200 feet above the Pacific. Amid the bright flowers and clapboard homes the hissing rush of the surf, rolling across the sand eight to twelve feet high, is the major disturber of the peace. The plastic and concrete sprawl of Los Angeles could be on another planet. The peace brought the artists—Laguna has a museum devoted to the works of early Californian painters—and the ocean brought the surfers.

In the early 1960s Laguna was a sleepy little township with the sort of mix to be found in many Californian communities. The American Legion and the Daughters of the American Revolution thrived alongside the artistic community—indeed, the local high school football team was called the Laguna Beach Artists. Once a year on Labor Day, things got a mite out of hand on the 'Walkaround', a fifty-year-old custom in which the passing of summer was mourned, by a walk from bar to bar along the Pacific Coast Highway. Other than that, not much happened in Laguna.

But in the mid-1960s, the number of young surfers was growing and they brought with them other young people eager to live a rude life away from the cities; among them were the Brotherhood. A mile from the beach, a cluster of about fifty houses made up a sub-suburb called Woodland Drive beneath one of the sandstone hills in Laguna Canyon. It was a ramshackle area of gorse and dirt tracks, running down to badly paved streets and a single street light, but it was home for the colony of youngsters. The Brotherhood moved into four white-painted houses.

The scene was painted for a journalist some years later by one of the young men who lived in the Drive: 'I went to school in Hollywood and got into surfing and just like everyone else I wound up in Laguna. Things were happening then, opening up. The chicks were seeing things and there was a lot of grass and there was a vibe that you could make it with love and digging each other... I'd go down to Laguna more and more and finally I just moved into a place on the Canyon with some chicks and a couple of other guys. It was cheap and it was fun. You know the bond, the thing that tied us up together was surfing and dope and balling. We'd get up early in the morning, stay out in the sun all day and somebody always had more grass... Then this cat Farmer John started coming around and he was really into acid. So we did a lot of acid and dug it and Farmer John was putting down a heavy brother-love rap.' Griggs, a charismatic figure, began to enlarge the Brotherhood, drawing people in to create concentric rings which spread out from the central core of Brothers who had moved into Laguna.

The Brotherhood and its apostles were no longer occasional dealers. ne business was now a full-time occupation, financing the way they lived and the opening of the Mystic Arts World Store. At first, there had been odd deals of marijuana tucked inside matchboxes—and, the next moment, consignments of kilos. They arrived in Laguna so often that Lynd for one no longer found anything strange in this new life. 'It was just an everyday occurrence. We would buy kilos of marijuana across the Mexican border and sell them to other Brothers who would turn round and sell them, with the money going to the store. Then there was the LSD sales. Different people would go up to San Francisco which was the place to buy LSD and buy it in quantity to resell in Laguna,' he said.

As far as the marijuana was concerned, 'there could be anything from one kilo to as many as 300 to possibly 400 kilos at a time. I had taken kilos most likely on half a dozen occasions, possibly even a dozen occasions to places like San Francisco. Most of the money that was made was turned into the shop. Randall would collect money and Johnny Griggs would collect...'The two men were at the centre of the distribution system for the marijuana. According to Lynd, kilos were bought for $45, sold to Griggs and Randal for $65-$70, who then sold them for $100 or more. The buyers broke down the kilos to smaller dealers selling on the streets. Sales were not confined to the houses up in Woodland Drive. At night, the area round the Taco Bell fast-food stand, close to the Mystic Arts World, and crowded with surfers, beach bums and hippies, buying and trading small deals.

Lynd may have sounded nonchalant about the source of supply in Mexico, but the Brothers worked out a careful system centred on a town near Tijuana, a few miles south of San Diego. The long-haired Brothers may have seemed unlikely company for an officer in the Mexican police, but once a month they met for a quiet chat. There was not much that a policeman missed in a tiny Mexican town. A group of young Americans renting a house, coming and going with battered cars and trucks on the dusty roads in and out of town stood out among the local peasantry and the tourist buses thundering past. But a policeman has to live, even a local police chief. He had arranged their tenancy and offered to watch the house for a few dollars; for $30 a month, the Brothers paid him not to. In return for this outlay, the Brothers could buy their marijuana, hide it in the fenders of their cars and drive across the border without problems. No one seemed to bother them.

Griggs was so excited by the Brothers' successes, he would telephone Leary at Millbrook: 'Hey, Uncle Tim, we've just moved half a ton of grass and we've got some righteous acid.' The calls came in about once a week, but Leary tended to dismiss them, although Jack, his son, now in his teens, decided he would go west to California and have a look. He returned home to Millbrook filled with enthusiasm. One evening, he told his father, Griggs was counting out a stack of $1,000 bills by the light of candies. The air in Griggs' home on Woodland Drive was heavy with incense and the smell of marijuana. Jack Leary leant over, took a banknote and lit it with one of the candles. As a thousand dollars disappeared in a bright flame, black ash and the smell of burning paper, no one batted an eyelid.

But back at Millbrook, Leary was astonished. He called Griggs and offered to repay the $1,000 dollars, but Griggs would have none of it. 'Hey, Uncle Tim, we all wanted to burn a thousand-dollar bill. It was a great thing he did, very enlightening.'

Leary was becoming a frequent visitor to the West Coast as he toured the country lecturing and lobbying. When he decided to visit Laguna with Rosemary, his latest wife, he was greeted like an elder statesman and given conducted tours of the Brothers' achievements. He said: 'They were running the store which was an enormous, beautiful place. Just a group of guys who were pooling all their resources to raise consciousness. They were dedicating their lives to becoming better people. They could see it happening round the country. They were pioneers.'

Hollingshead, the man who had given Leary his first LSD experience, had returned from Britain and joined Leary in Laguna. 'The Brotherhood felt they were leading a new society,' he remembered. 'California was the country of the future. It was as if the culture had entered into them. They were responding. Righteous dealing was a sacrament, with Tim as their guru. I have always found them very gracious people, very honest, very wise—but also very naive. It was the Dead-end Kids who took acid and fell in love with beauty.' The Brothers were making money out of dealing, but Hollingshead said: 'Griggs was not thinking in those terms. He was only thinking of getting the psychedelics on the streets so that people could take them. They were totally committed. They had tremendous determination. They were all very tough; once they were moving dope, they were manic. When the stuff came from Mexico they did this non-stop thing...'

http://www.druglibrary.net/schaffer/lsd/books/bel3.htm

At Christmas 1969, the Mystic Arts World Store burned down in circumstances no one could ever explain. The fire was not considered a terrible loss. The idea of eventually living off the profits of the shop had been doomed by the drugs that were dealt to get it started. Everyone grew too fascinated in drug dealing to want to serve in the store. As the smoke cleared, the Brothers with the rest of the psychedelic movement were heading towards the Badlands where outlaws survive—at a price.

The Mystic Arts World Store was opposite a Mexican fast-food stand on South Laguna Beach. At the front it sold the sort of things to be found in a thousand similar stores that were sprouting up across the America of 1966 and 1967—home-made clothes, natural foods, leatherware, brass, tapestries, pipes and papers for marijuana smoking: another 'head shop', a sort of frontier store for America's newest pioneers, the hippies; a corner shop for the colony of young people moving into Laguna Beach, south of Los Angeles, to enjoy a 'Haight-Ashbury on sea'.

But the real business of Mystic Arts lay at the back in the meditation room. The floor was covered from wall to wall by foam rubber overlaid with thick carpeting, making visitors feel as though they were walking on a huge, luxurious bed. At one end, a small waterfall tumbled into an indoor rock garden. The sound was soft and rhythmic, lulling. In another corner stood a water pipe. Scatter cushions had been left here and there for customers, who removed their shoes before entering, to loll at their ease. A group of young men in their twenties might be sitting round at the beginning of an LSD session: their hair was long; they wore patched jeans and loose shirts, embroidered waistcoats over painted T-shirts and single strings of thick, crude beads. Some had the deep sunburn that you find in this part of California on surfers, where the heat of the sun has burnt into the skin, magnified by the sea-water, and left a rich tan. Others had the thick-set, hard-muscled build of mechanics.

They were men with a cause, yet theirs was not quite the burning ardor of the radicals elsewhere in the country, streaming across the campuses towards the administration blocks and screaming against betrayal, grappling with the police as they denounced L.B.J. and vowing they would never fight in Vietnam. Theirs was another kind of fervor: there was no violence, just the unswerving confidence of missionaries going about their work.

The meditation room was, on occasion, the private chapel of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, a legally incorporated religious charity. At other times it was the front office of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, drug dealers extraordinary. The essence of the Brotherhood might well be summed up in Owsley's 'chemistry is theology'.

The man to watch at the LSD sessions was a short, stocky character wearing a Hopi Indian headband and flowing green Eastern trousers and shirt. John Griggs, dark and intense with bright blue eyes, was the founding figure of the Brotherhood: a man who had discovered LSD in dramatic circumstances.

At the time, Griggs, approaching his middle twenties, was the leader of a marijuana-smoking south Los Angeles motorcycle gang, preying on supermarkets. Largely unschooled, Griggs was a wandering adventurer who had earned the name of 'Farmer John' after disappearing into the Californian mountains to live as a trapper. He rode with his pack along the freeways and highways that criss-crossed Los Angeles in search of fresh excitement. On a summer night he led his gang through Hollywood towards Beverly Hills and Mulholland Drive. According to the grapevine, a well-known Hollywood film producer up there kept a cache of pure LSD in his refrigerator. Griggs and the gang decided it was time they tried this LSD stuff everyone was talking about.

They burst in on the producer during a dinner party. All the guests froze as the gang, armed with guns and knives, came out of the darkness... but all they wanted was the LSD, and they took it. The host was so relieved that he rushed out to the driveway as they started up their motorcycles and cried after them: 'Have a great trip, boys. Jesus, I thought it was something serious.'

The gang roared out of Los Angeles towards the vast, high acres of Joshua Tree National Park beyond the city. They climbed higher and higher into the hills among the yucca trees until they were above Palm Springs and, at midnight, they came to a halt. Motorcycles parked in a group, they stood round in the clear, sharp mountain air and shared out the LSD, made by Sandoz. Each man swallowed the equivalent of 1,000 micrograms, four times a normal dose, and wandered off to await the result. It was cold and the yuccas with their twisted stems and shrouds of dead leaves cast fantastic shapes in the gloom.

As the sun burst across the sky at dawn, hours later, Griggs threw his gun into the dry scrub and shouted: 'This is it. This is it.' The gang regrouped round their motorbikes, shaken and overwhelmed. All had thrown away their weapons. They started home for Anaheim, a flat Los Angeles suburb of pale-coloured houses, and what was to be a new life.

Griggs was the proselytizer, the moving spirit. He talked to old schoolfriends like Glen Lynd and Calvin Delaney. Lynd had already tried marijuana and now took the LSD Griggs passed on to him. Like Griggs, Lynd was in his middle twenties and something of a drifter. The group that began to assemble totalled nine. Most of the young men, all in their early or middle twenties, came from Anaheim. Michael Randall was from Long Beach, although he had attended Anaheim Western High School. He started smoking marijuana in 1963 but remained on the edge of the group, since, he was finishing a course in business administration at California State College.

At first, the group did little more than meet at the weekends to try out the psychedelics, but Griggs had wider visions. He urged the others to move with him out of Los Angeles, east to Modjeska Canyon, in the countryside beyond the city. The group shared a couple of houses, feeling, like Alpert and Leary had felt at Harvard, that they had 'something wonderful in common'. Those who had jobs continued to work—Russ Harrigan for example was a longshoreman—but all now began a little drug dealing as well. Lynd and Harrigan went down to San Pedro with the odd kilo of marijuana brought back from trips to Mexico, and all the group sold LSD from San Francisco to visitors to Modjeska Canyon. Several of them enrolled in research programs at the University of California, Los Angeles, in order to continue using the psychedelics for free.

But on Wednesday nights they came together to talk about their futures. Lynd said later: 'There was hopeful thought of buying land... the purpose was to buy it so people could live on it. We could farm it or whatever.' Plans began to form round the notion. Lynd had heard Leary lecturing and had been impressed. Griggs went east to meet him at Millbrook. Leary was taken with him: 'an incredible genius' was how he described Griggs; 'although unschooled and unlettered he was an impressive person. He had this charisma, energy, that sparkle in his eye. He was good-natured, surfing the energy waves with a smile on his face.' As far as Griggs was concerned, Leary was his guru, one with some useful practical ideas.

In the summer of 1966 when Griggs went to Millbrook, Leary was working on his plans for the formation of the League of Spiritual Discovery. Griggs and his friends seemed to have a good thing going out there in the West, so why not set up something similar? The new psychedelic religion was not something all-embracing and spiritually omnipotent. There was no Pope to set out the prescribed dogma. This religion was about a new kind of spiritual freedom which you found for yourself. The basic tenets of the League included: 'enthusiastic acceptance of the sacramental method by the young... a recognition that the search for God is a private affair... the rituals spring from experiences of the small worship group... the leaven works underground... friends initiate, teach, prepare and guide...'

Ten days after California banned LSD in October 1966, Lynd, his wife and a friend walked into the offices of a Los Angeles attorney on Sunset Boulevard and signed the papers incorporating the Brotherhood; Lynd was the only Brother who did not have a criminal record, so he was designated to organize the incorporation. According to the legal papers, the Brotherhood, tax exempt, was dedicated 'to bring to the world a greater awareness of God through the teachings of Jesus Christ, Rama-Krishnam Babaji, Paramahansa Yogananda, Mahatma Gandhi and all true prophets and apostles of God'. Was there a hint of Leary's influence in this list? Griggs had recently returned from a trip to the East, and the Brothers were largely 'unschooled'.

To achieve its ends, the Brotherhood intended to 'buy, manage and own and hold real and personal property necessary and proper for a place of public worship and carry on educational and charitable work'. Was there an echo of the League's tenets in article 4-D which read: 'We believe in the sacred right of each individual to commune with God in spirit and in truth as it is empirically revealed to him'? This was 'a recognition that the search for God is a private matter', written another way.

Lynd said years later: 'Well, it was John Griggs' main idea to incorporate because he had talked to Leary, and it was possible to incorporate to become tax-exempt as far as land goes and, if and when marijuana ever becomes legal, become tax-exempt on marijuana.' There were no fixed rules for joining; no name signing or ritual. But there was one basic rule among the Brothers—they believed in taking as much of the psychedelics as possible, the largest doses of LSD they could buy. The articles of association did not explain how the Brotherhood intended to buy its land or establish its place of worship. You cannot really tell a lawyer or the State of California that you intend to raise capital by breaking the law—by massive dealing in drugs.

Laguna Beach is an artists' colony and resort thirty miles south of Los Angeles. There are only two roads into the town: the Pacific Coast Highway or, from inland, down Laguna Canyon. The town itself, like the Stage of an amphitheatre, sits at the base of a semicircle of sandstone hills rising to 1,200 feet above the Pacific. Amid the bright flowers and clapboard homes the hissing rush of the surf, rolling across the sand eight to twelve feet high, is the major disturber of the peace. The plastic and concrete sprawl of Los Angeles could be on another planet. The peace brought the artists—Laguna has a museum devoted to the works of early Californian painters—and the ocean brought the surfers.

In the early 1960s Laguna was a sleepy little township with the sort of mix to be found in many Californian communities. The American Legion and the Daughters of the American Revolution thrived alongside the artistic community—indeed, the local high school football team was called the Laguna Beach Artists. Once a year on Labor Day, things got a mite out of hand on the 'Walkaround', a fifty-year-old custom in which the passing of summer was mourned, by a walk from bar to bar along the Pacific Coast Highway. Other than that, not much happened in Laguna.

But in the mid-1960s, the number of young surfers was growing and they brought with them other young people eager to live a rude life away from the cities; among them were the Brotherhood. A mile from the beach, a cluster of about fifty houses made up a sub-suburb called Woodland Drive beneath one of the sandstone hills in Laguna Canyon. It was a ramshackle area of gorse and dirt tracks, running down to badly paved streets and a single street light, but it was home for the colony of youngsters. The Brotherhood moved into four white-painted houses.

The scene was painted for a journalist some years later by one of the young men who lived in the Drive: 'I went to school in Hollywood and got into surfing and just like everyone else I wound up in Laguna. Things were happening then, opening up. The chicks were seeing things and there was a lot of grass and there was a vibe that you could make it with love and digging each other... I'd go down to Laguna more and more and finally I just moved into a place on the Canyon with some chicks and a couple of other guys. It was cheap and it was fun. You know the bond, the thing that tied us up together was surfing and dope and balling. We'd get up early in the morning, stay out in the sun all day and somebody always had more grass... Then this cat Farmer John started coming around and he was really into acid. So we did a lot of acid and dug it and Farmer John was putting down a heavy brother-love rap.' Griggs, a charismatic figure, began to enlarge the Brotherhood, drawing people in to create concentric rings which spread out from the central core of Brothers who had moved into Laguna.

The Brotherhood and its apostles were no longer occasional dealers. ne business was now a full-time occupation, financing the way they lived and the opening of the Mystic Arts World Store. At first, there had been odd deals of marijuana tucked inside matchboxes—and, the next moment, consignments of kilos. They arrived in Laguna so often that Lynd for one no longer found anything strange in this new life. 'It was just an everyday occurrence. We would buy kilos of marijuana across the Mexican border and sell them to other Brothers who would turn round and sell them, with the money going to the store. Then there was the LSD sales. Different people would go up to San Francisco which was the place to buy LSD and buy it in quantity to resell in Laguna,' he said.

As far as the marijuana was concerned, 'there could be anything from one kilo to as many as 300 to possibly 400 kilos at a time. I had taken kilos most likely on half a dozen occasions, possibly even a dozen occasions to places like San Francisco. Most of the money that was made was turned into the shop. Randall would collect money and Johnny Griggs would collect...'The two men were at the centre of the distribution system for the marijuana. According to Lynd, kilos were bought for $45, sold to Griggs and Randal for $65-$70, who then sold them for $100 or more. The buyers broke down the kilos to smaller dealers selling on the streets. Sales were not confined to the houses up in Woodland Drive. At night, the area round the Taco Bell fast-food stand, close to the Mystic Arts World, and crowded with surfers, beach bums and hippies, buying and trading small deals.

Lynd may have sounded nonchalant about the source of supply in Mexico, but the Brothers worked out a careful system centred on a town near Tijuana, a few miles south of San Diego. The long-haired Brothers may have seemed unlikely company for an officer in the Mexican police, but once a month they met for a quiet chat. There was not much that a policeman missed in a tiny Mexican town. A group of young Americans renting a house, coming and going with battered cars and trucks on the dusty roads in and out of town stood out among the local peasantry and the tourist buses thundering past. But a policeman has to live, even a local police chief. He had arranged their tenancy and offered to watch the house for a few dollars; for $30 a month, the Brothers paid him not to. In return for this outlay, the Brothers could buy their marijuana, hide it in the fenders of their cars and drive across the border without problems. No one seemed to bother them.

Griggs was so excited by the Brothers' successes, he would telephone Leary at Millbrook: 'Hey, Uncle Tim, we've just moved half a ton of grass and we've got some righteous acid.' The calls came in about once a week, but Leary tended to dismiss them, although Jack, his son, now in his teens, decided he would go west to California and have a look. He returned home to Millbrook filled with enthusiasm. One evening, he told his father, Griggs was counting out a stack of $1,000 bills by the light of candies. The air in Griggs' home on Woodland Drive was heavy with incense and the smell of marijuana. Jack Leary leant over, took a banknote and lit it with one of the candles. As a thousand dollars disappeared in a bright flame, black ash and the smell of burning paper, no one batted an eyelid.

But back at Millbrook, Leary was astonished. He called Griggs and offered to repay the $1,000 dollars, but Griggs would have none of it. 'Hey, Uncle Tim, we all wanted to burn a thousand-dollar bill. It was a great thing he did, very enlightening.'

Leary was becoming a frequent visitor to the West Coast as he toured the country lecturing and lobbying. When he decided to visit Laguna with Rosemary, his latest wife, he was greeted like an elder statesman and given conducted tours of the Brothers' achievements. He said: 'They were running the store which was an enormous, beautiful place. Just a group of guys who were pooling all their resources to raise consciousness. They were dedicating their lives to becoming better people. They could see it happening round the country. They were pioneers.'

Hollingshead, the man who had given Leary his first LSD experience, had returned from Britain and joined Leary in Laguna. 'The Brotherhood felt they were leading a new society,' he remembered. 'California was the country of the future. It was as if the culture had entered into them. They were responding. Righteous dealing was a sacrament, with Tim as their guru. I have always found them very gracious people, very honest, very wise—but also very naive. It was the Dead-end Kids who took acid and fell in love with beauty.' The Brothers were making money out of dealing, but Hollingshead said: 'Griggs was not thinking in those terms. He was only thinking of getting the psychedelics on the streets so that people could take them. They were totally committed. They had tremendous determination. They were all very tough; once they were moving dope, they were manic. When the stuff came from Mexico they did this non-stop thing...'

http://www.druglibrary.net/schaffer/lsd/books/bel3.htm

At Christmas 1969, the Mystic Arts World Store burned down in circumstances no one could ever explain. The fire was not considered a terrible loss. The idea of eventually living off the profits of the shop had been doomed by the drugs that were dealt to get it started. Everyone grew too fascinated in drug dealing to want to serve in the store. As the smoke cleared, the Brothers with the rest of the psychedelic movement were heading towards the Badlands where outlaws survive—at a price.

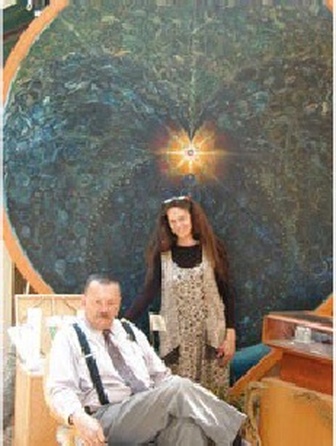

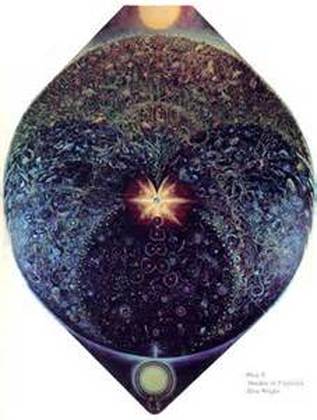

Taxonomic Mandala, Dion Wright

http://www.dionwright.com/mandala.htm

"Taxonomic Mandala of Life on Earth"

oil on plywood; Woodstock 1965-66; 8' by 11'6"

$150,000; enquire, [email protected]

“The Taxonomic Mandala of Life on Earth” was painted at Woodstock in oil on three-quarter inch plywood in 1965 and 1966 by Dion Wright. It measures twelve feet high and eight feet wide, plus a few inches for the oak frame (not shown here). All together, it weighs over 200 pounds, but disassembles into four parts, two half-frames and two half-paintings, for ease of handling

http://www.dionwright.com/mandala.htm

"Taxonomic Mandala of Life on Earth"

oil on plywood; Woodstock 1965-66; 8' by 11'6"

$150,000; enquire, [email protected]

“The Taxonomic Mandala of Life on Earth” was painted at Woodstock in oil on three-quarter inch plywood in 1965 and 1966 by Dion Wright. It measures twelve feet high and eight feet wide, plus a few inches for the oak frame (not shown here). All together, it weighs over 200 pounds, but disassembles into four parts, two half-frames and two half-paintings, for ease of handling

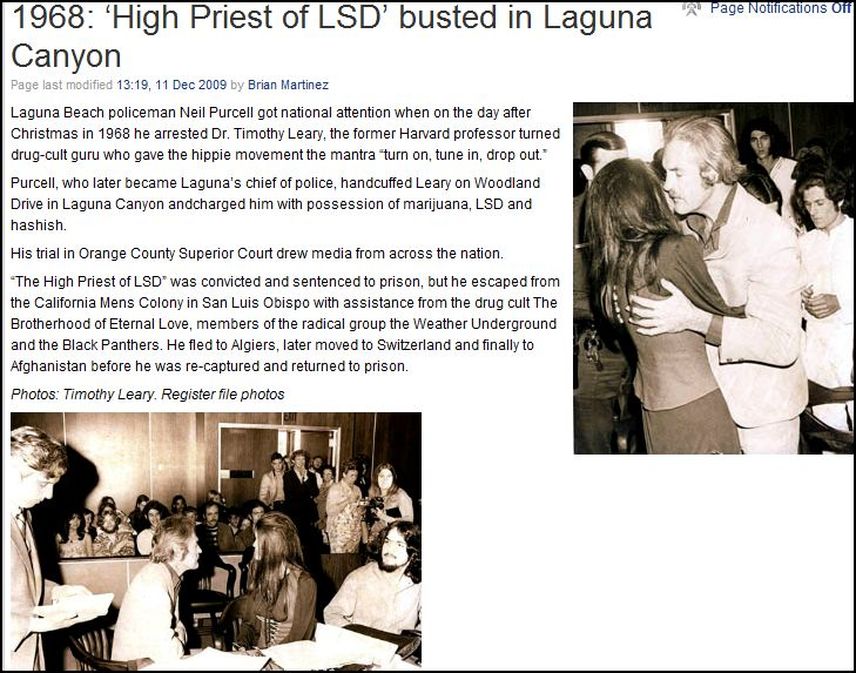

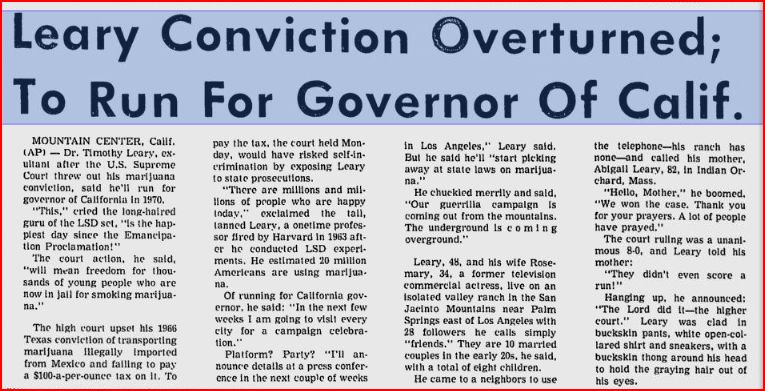

Leary Legacy

Blacklight Poster

Acid-Washed Surfers

Rainbow Surfboards

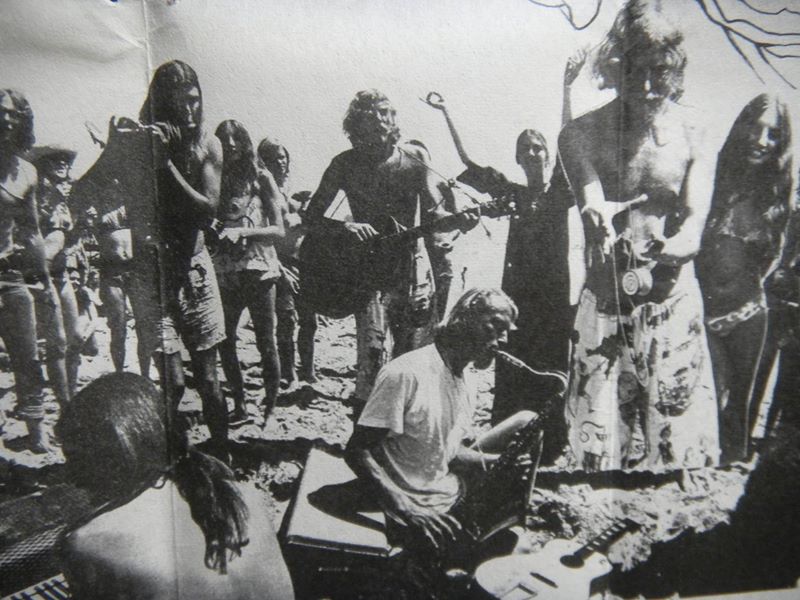

Brotherhood of Eternal Love, Canyon Acres, Laguna Canyon (David Nuuhiwa and John Gail), 1971, Photo Jeff Divine

Acid-Washed Surfers

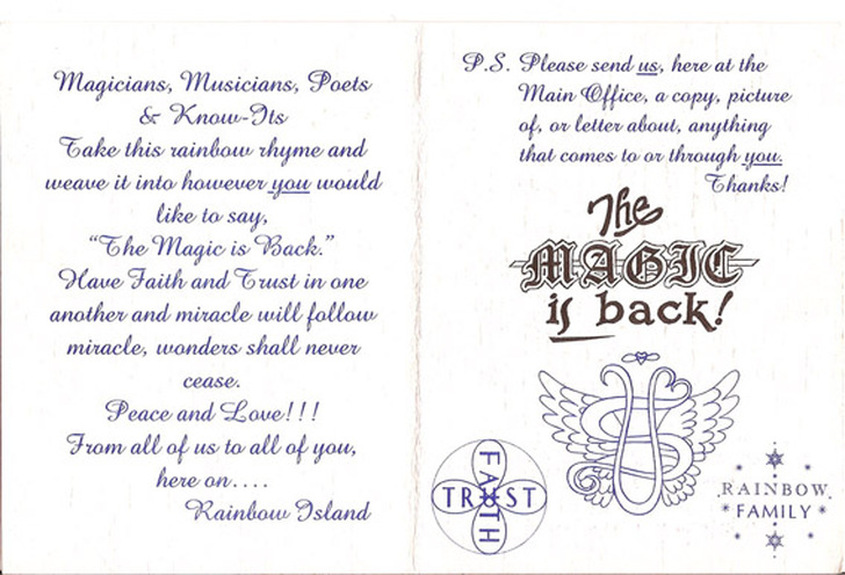

Rainbow Surfboards was founded by Johnny Gale (above) in 1969 in Laguna Beach, California. The late 1960’s and early 1970’s were a time of mind expansion, new music, and pure cosmic surf soul. John Gale was Mike Hynson's business partner in Rainbow Surfboards, which the two founded as well as his best friend. Combining then business partner John Hawthorn with the ground breaking designs of Mike Hynson, the psychedelic airbrush art of John Bredin, Starman, as well as the Rainbow Island Family,… Rainbow Surfboards was born. The Rainbow movement and the turn of the decade were both times of transformation. Boards were going shorter, hair was getting longer and the next generation of surfing history was beginning; ultimately changing it forever. Rainbow Surfboards has a deep history that originates in Laguna Beach, from drug smuggling, to prison breaks, to evading the FBI, to psychedelic surfing.

Rainbow Surfboards was founded by Johnny Gale (above) in 1969 in Laguna Beach, California. The late 1960’s and early 1970’s were a time of mind expansion, new music, and pure cosmic surf soul. John Gale was Mike Hynson's business partner in Rainbow Surfboards, which the two founded as well as his best friend. Combining then business partner John Hawthorn with the ground breaking designs of Mike Hynson, the psychedelic airbrush art of John Bredin, Starman, as well as the Rainbow Island Family,… Rainbow Surfboards was born. The Rainbow movement and the turn of the decade were both times of transformation. Boards were going shorter, hair was getting longer and the next generation of surfing history was beginning; ultimately changing it forever. Rainbow Surfboards has a deep history that originates in Laguna Beach, from drug smuggling, to prison breaks, to evading the FBI, to psychedelic surfing.

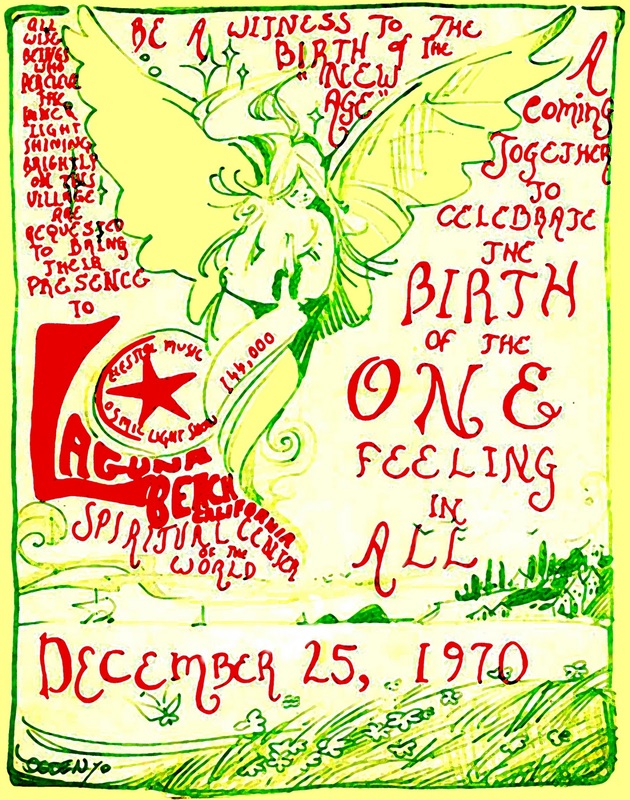

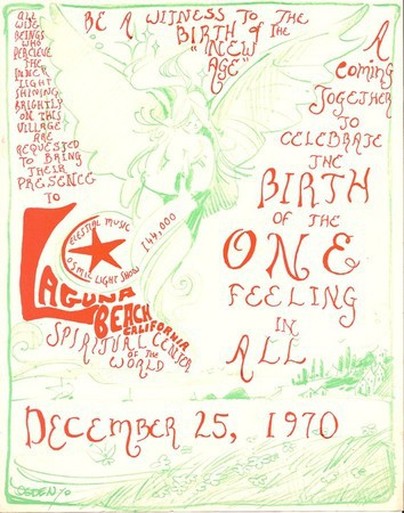

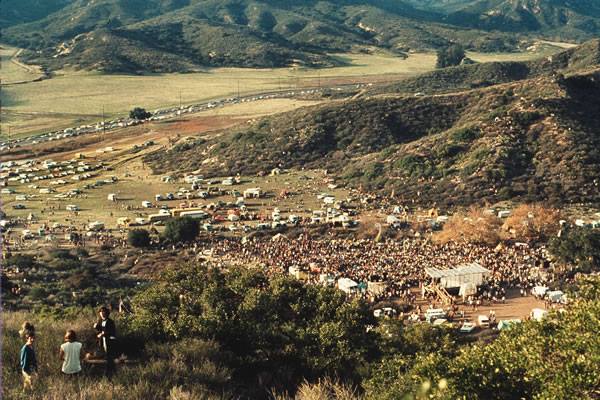

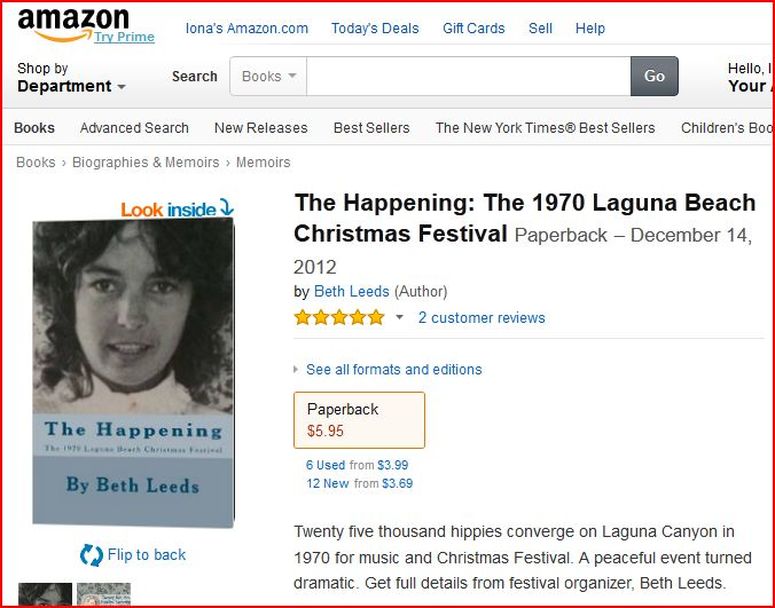

1970 Christmas Happening

UPDATE 2016Curtis Rainbow Helped to Organize the Biggest Hippie Happening in OC History. Now, He's HomelessMay 25, 2016

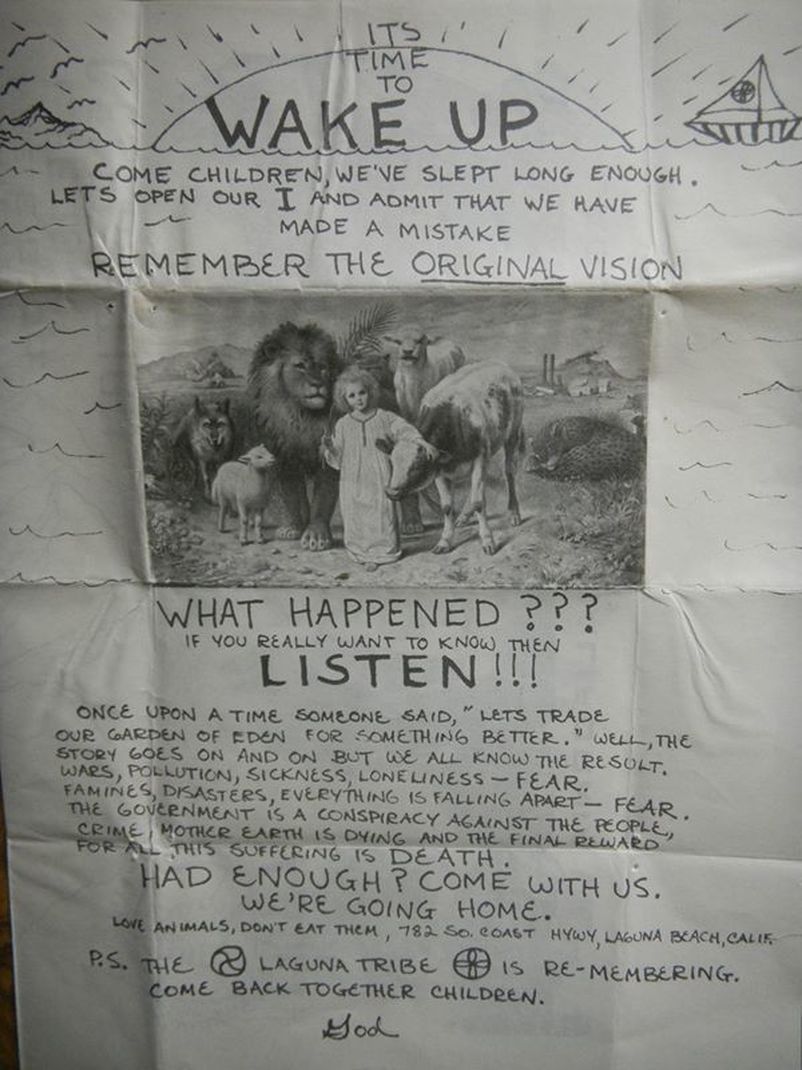

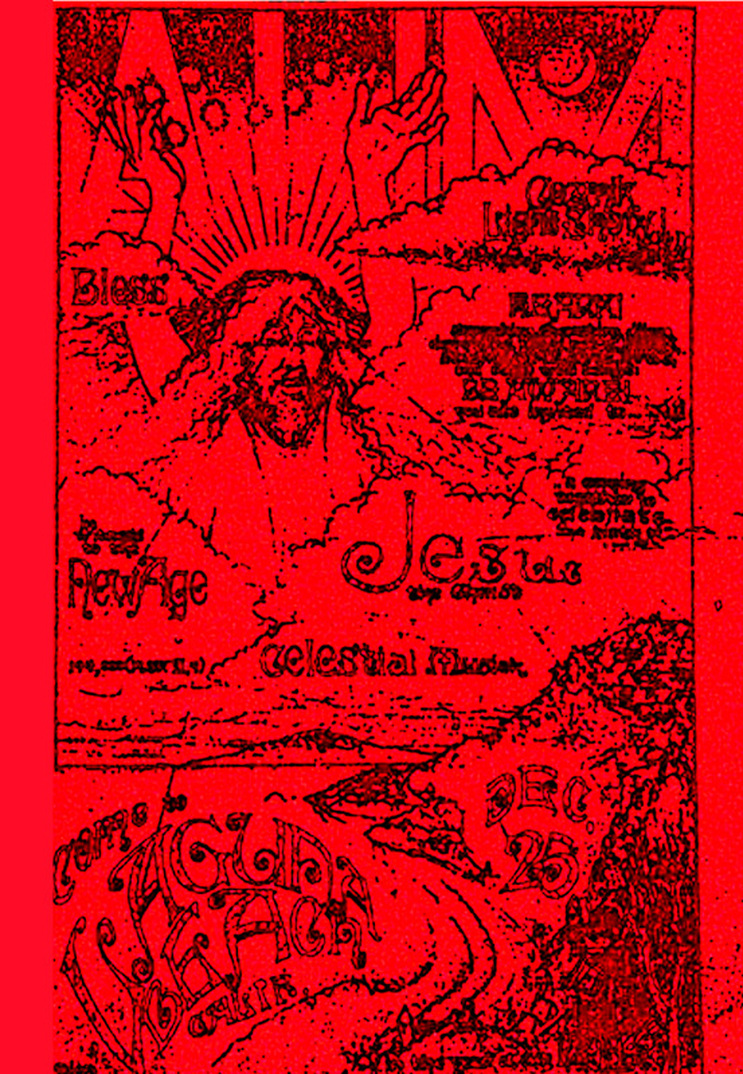

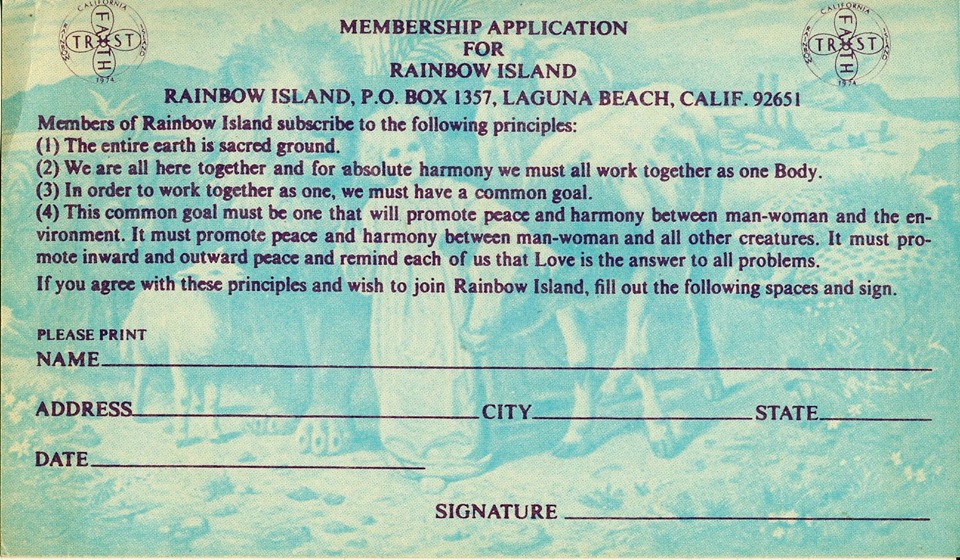

The outdoor concert at the top of Laguna Canyon is the most storied cultural event in Laguna Beach. But Rainbow's importance to Orange County's countercultural history didn't begin or end there. In the mid-1960s, Rainbow opened Laguna's first head shop, Things, and followed that in 1972 with a legendary vegetarian restaurant called Love Animals, Don't Eat Them. He even founded a hippie commune called Rainbow Island, which operated a nonprofit church and sustained itself by painting psychedelic shirts that were widely distributed at rock concerts and art festivals throughout Southern California and beyond.

http://www.ocweekly.com/news/curtis-rainbow-helped-to-organize-the-biggest-hippie-happening-in-oc-history-now-hes-homeless-7213851

The outdoor concert at the top of Laguna Canyon is the most storied cultural event in Laguna Beach. But Rainbow's importance to Orange County's countercultural history didn't begin or end there. In the mid-1960s, Rainbow opened Laguna's first head shop, Things, and followed that in 1972 with a legendary vegetarian restaurant called Love Animals, Don't Eat Them. He even founded a hippie commune called Rainbow Island, which operated a nonprofit church and sustained itself by painting psychedelic shirts that were widely distributed at rock concerts and art festivals throughout Southern California and beyond.

http://www.ocweekly.com/news/curtis-rainbow-helped-to-organize-the-biggest-hippie-happening-in-oc-history-now-hes-homeless-7213851

The successful airdrop of massive amounts of LSD at the Laguna Happening

gave new meaning to the phrase, "Dropping Acid".

gave new meaning to the phrase, "Dropping Acid".

Lp: 100% Unknown Fibers: Odd Lots, 1971 - Private.

This is a live recording at Laguna Beach festival.

This is a live recording at Laguna Beach festival.

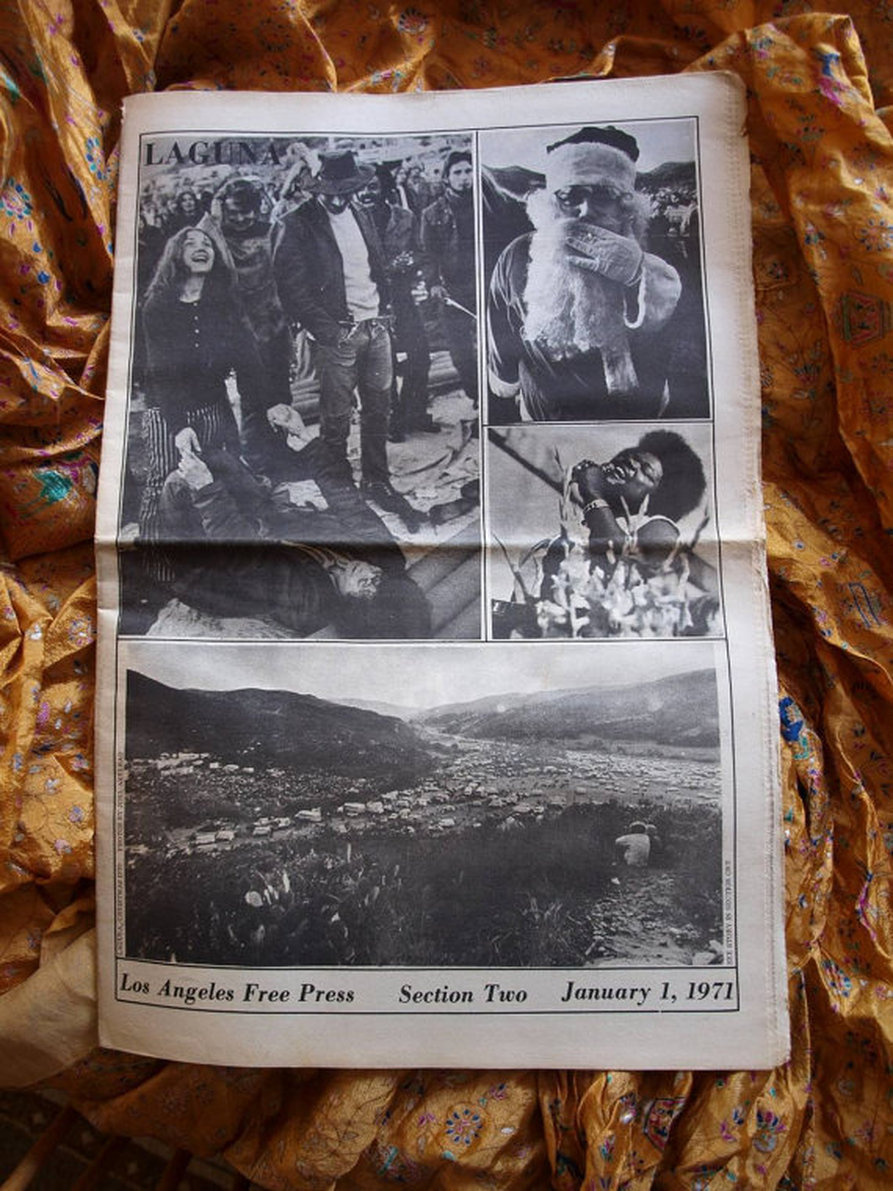

Laguna Beach's Great Hippie Invasion, 40 Years On

by Nick Schou

http://blogs.ocweekly.com/navelgazing/2010/12/laguna_beachs_great_hippie_inv.php

This week's meteorological mayhem aside, not much seems to happen in Laguna Beach that would qualify as strange, much less surreal. But things haven't always been that way. And by far the strangest thing that has ever happened in this otherwise sleepy coastal village, and probably the strangest thing that's ever happened in Orange County, was just starting to unfold there 40 years ago today.

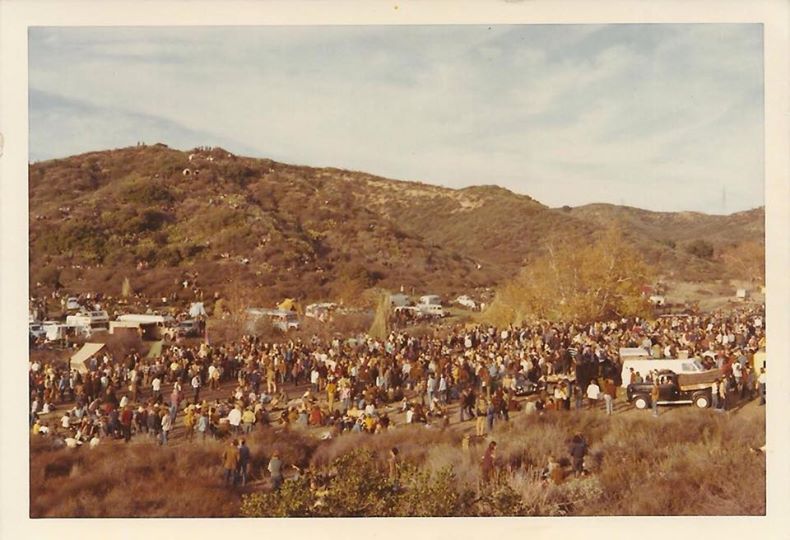

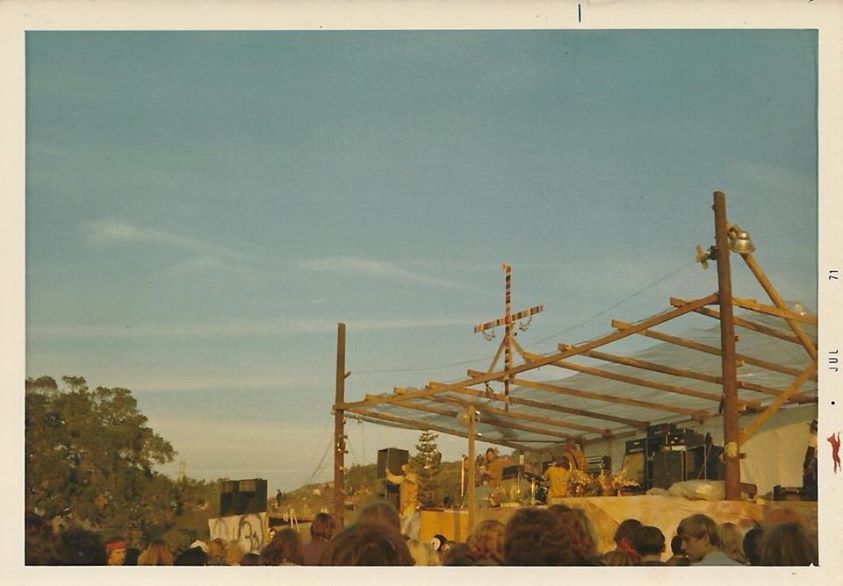

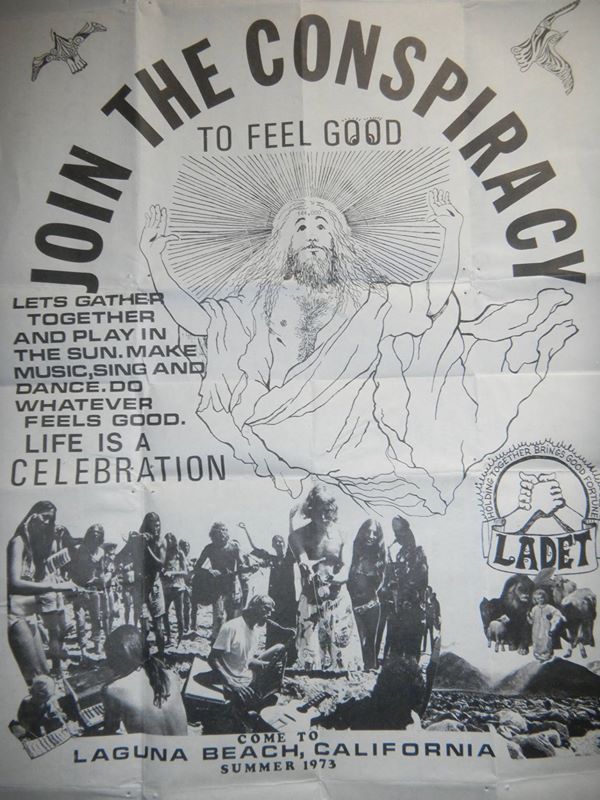

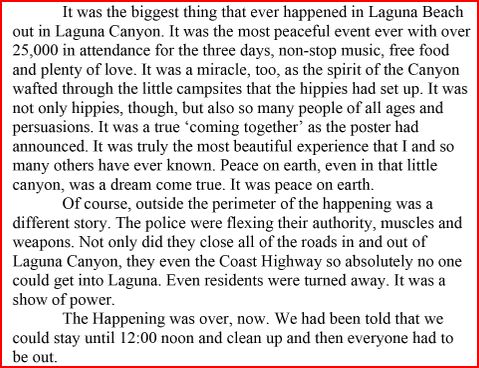

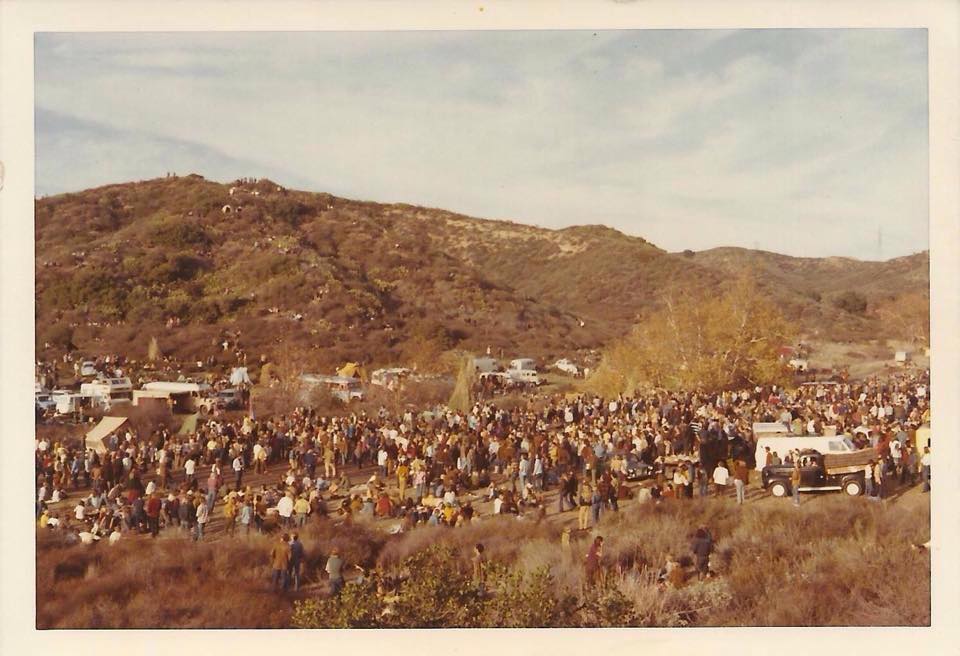

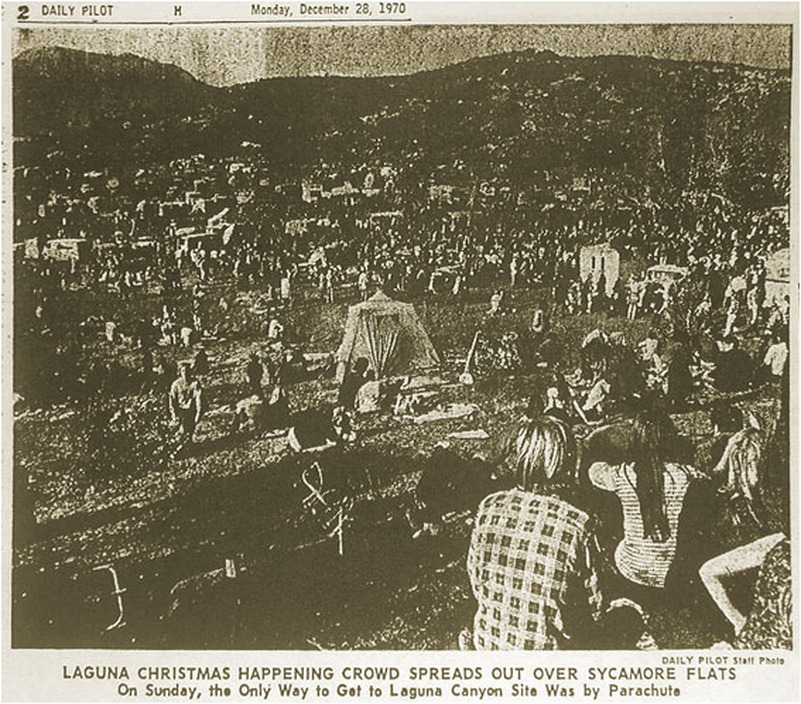

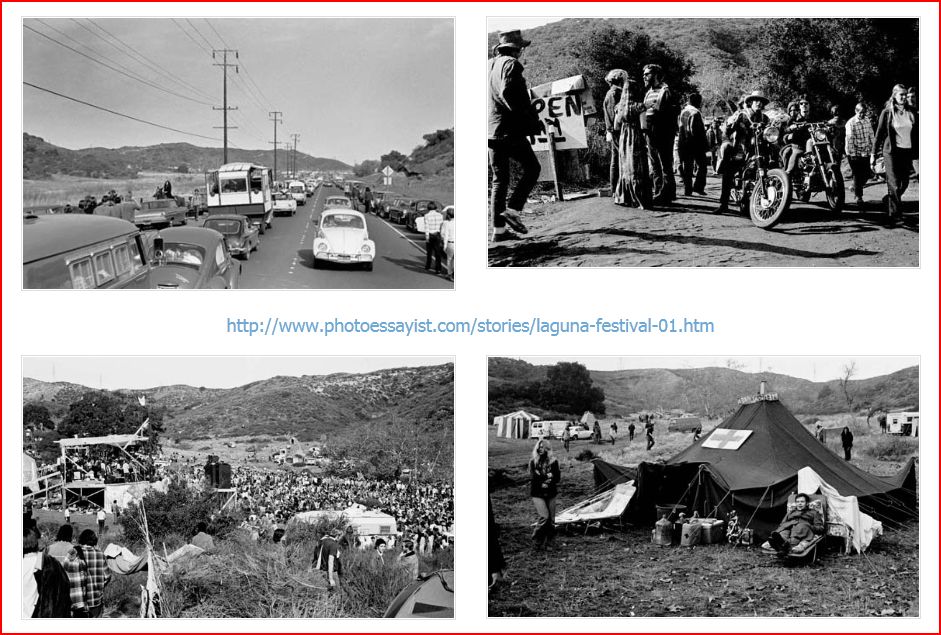

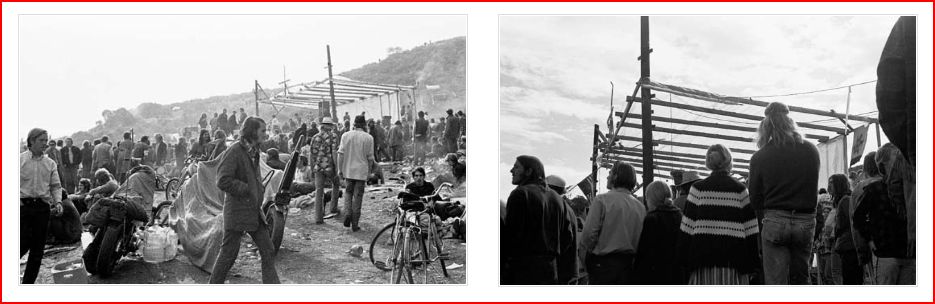

On this morning 40 years ago, hippies from all over California and beyond were massing in caravans that lined for miles on Pacific Coast Highway in both directions. They were gathering for a rock concert that originally had been billed as a "birthday party for Jesus" but which quickly became known as either the "Christmas Happening" or "The Great Happening." The concert, which was held in a grassy bowl at the top of Laguna Canyon known as Sycamore Flats, began on Christmas Day and ended three days later when hundreds of police officers and sheriff's deputies, who had already blocked off the town with barricades, forced stragglers onto buses and used bulldozers to bury everything left behind.

Invitations to the show had been hand-delivered to hippie communes up and down the Pacific Coast and beyoned, and each one contained a tab of Orange Sunshine acid, the trademark brand of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, a group of Timothy Leary acolytes and hash smugglers who just two months earlier had raised funds to help Leary escape from prison. Halfway during the first day of the show, someone parachuted into the show--despite rumors to the contrary, the man wasn't Leary and nobody ever found out who he was--and later, another airplane flew overhead and thousands more of of the acid-bearing cards tumbled from the sky.

The Weekly first wrote about this amazing spectacle--which at least one organizer, artist Dion Wright, believes was the "true death of hippiedom"--12 years ago, in a fascinating story by freelancer Bob Emmers, which you can read here. That article led yours truly on a several years journey to discover more about both this strange event and the Brotherhood of Eternal Love itself, which I wrote about earlier this year in--shameless plug alert--my book Orange Sunshine: The Brotherhood of Eternal Love and Its Quest to Spread Peace, Love and Acid to the World, which is still on bookshelves and available online.

Documentary film-maker William Kirkley is making a film about the Brotherhood also called Orange Sunshine, and he's busy compiling rare footage of the show, including the apocryphal-seeming acid drop. You can view a pretty mind-blowing trailer for his film here. There's also a great piece courtesy of the Lama Workshop that features photographs and other artwork pertaining to the show that makes for a fun read.

For rain-soaked Lagunans, if nothing else, the thought of all this probably breaks down in two distinct ways. Folks of the hippie-hating variety can take solace in the fact that nothing like this is likely to happen in their town again. For others, including some residents who were actually there when the show happened, it's more likely a sad reminder of how much things have changed, not just in their town, but in our nation and world as a whole. Nothing that a few plane-loads of acid couldn't fix, though...

by Nick Schou

http://blogs.ocweekly.com/navelgazing/2010/12/laguna_beachs_great_hippie_inv.php

This week's meteorological mayhem aside, not much seems to happen in Laguna Beach that would qualify as strange, much less surreal. But things haven't always been that way. And by far the strangest thing that has ever happened in this otherwise sleepy coastal village, and probably the strangest thing that's ever happened in Orange County, was just starting to unfold there 40 years ago today.

On this morning 40 years ago, hippies from all over California and beyond were massing in caravans that lined for miles on Pacific Coast Highway in both directions. They were gathering for a rock concert that originally had been billed as a "birthday party for Jesus" but which quickly became known as either the "Christmas Happening" or "The Great Happening." The concert, which was held in a grassy bowl at the top of Laguna Canyon known as Sycamore Flats, began on Christmas Day and ended three days later when hundreds of police officers and sheriff's deputies, who had already blocked off the town with barricades, forced stragglers onto buses and used bulldozers to bury everything left behind.

Invitations to the show had been hand-delivered to hippie communes up and down the Pacific Coast and beyoned, and each one contained a tab of Orange Sunshine acid, the trademark brand of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, a group of Timothy Leary acolytes and hash smugglers who just two months earlier had raised funds to help Leary escape from prison. Halfway during the first day of the show, someone parachuted into the show--despite rumors to the contrary, the man wasn't Leary and nobody ever found out who he was--and later, another airplane flew overhead and thousands more of of the acid-bearing cards tumbled from the sky.