John Griggs

The Farmer

"Hippie Messiah"

When the hippie generation first emerged around 1966, they had a tremendous, global impact almost immediately. The hippies influenced the Beatles, for example, not the other way around. The movement was actually deeply ethical and spiritual, and involved respect for nature and native cultures, as well as a deep suspicion for the oil companies, who had emerged as the world’s dominant corporations. Their relentless campaign to turn everything in America into plastic really annoyed us. Plastic was a bad word to hippies. We hated it. One thing we didn’t hate was marijuana, which was the primary sacrament from day one. All sorts of other plants and substances quickly followed. We needed people to cultivate, transport and sell these sacraments. These people were closer to priests than outlaws to us since they were providing our sacraments at great personal jeopardy.

It’s no accident that the most spiritually advanced hippie clan was also the most successful smuggling and dealing operation in North America. I speak of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love based out of Laguna Beach, California and founded by hippie saint Johnny Griggs.

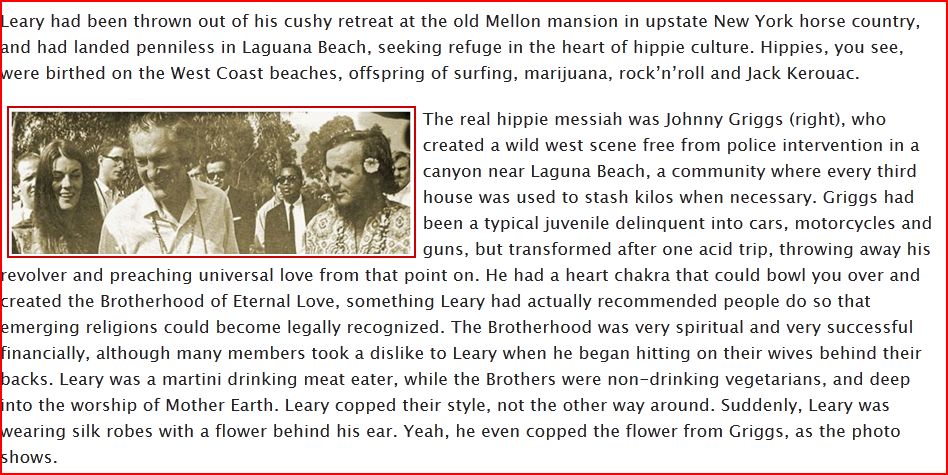

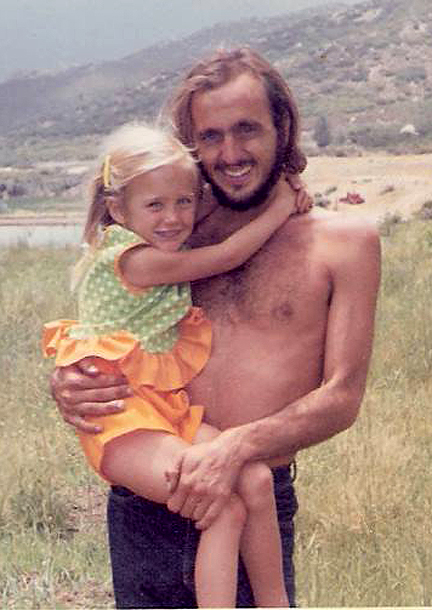

The Brotherhood became known as the hippie mafia, and their story became a tale of drug smuggling and police interventions. The Godfather was John, picture at the left with his kids and a surfboard he never surfed on, but was just posing with. But the hippie mafia story is a little bit like the blind man describing an elephant by touching its toe. Nick Schou recently wrote an entertaining book on the Brotherhood and he couldn’t understand why John’s widow couldn’t relate to it. The illegal part of hippie life is like the visible part of an iceberg. The heart and soul of the culture lies submerged, out-of-view. And that is the spiritual side, known to made members. We have no official ceremony for this initiation, but we know how to recognize when one gets “zapped” by this unique, non-violent form of spirituality. But to the population at large, the Brotherhood of Eternal Love remains just another “crime syndicate.”

It’s no accident that the most spiritually advanced hippie clan was also the most successful smuggling and dealing operation in North America. I speak of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love based out of Laguna Beach, California and founded by hippie saint Johnny Griggs.

The Brotherhood became known as the hippie mafia, and their story became a tale of drug smuggling and police interventions. The Godfather was John, picture at the left with his kids and a surfboard he never surfed on, but was just posing with. But the hippie mafia story is a little bit like the blind man describing an elephant by touching its toe. Nick Schou recently wrote an entertaining book on the Brotherhood and he couldn’t understand why John’s widow couldn’t relate to it. The illegal part of hippie life is like the visible part of an iceberg. The heart and soul of the culture lies submerged, out-of-view. And that is the spiritual side, known to made members. We have no official ceremony for this initiation, but we know how to recognize when one gets “zapped” by this unique, non-violent form of spirituality. But to the population at large, the Brotherhood of Eternal Love remains just another “crime syndicate.”

But something really deep happened when I discovered John Griggs, founder of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love. I instantly realized John was a true hippie messiah, and like all messiahs had died at the zenith of his creative powers, a tragic loss for the world. John’s heart was immense and his love for the world boundless. James put me on the path of action, The Pranksters put me on the path of fun, Stephen put me on the path of wisdom, but John Griggs put me on the path of love. It’s strange how some of the most important figures in the history of the counterculture remain unknown and uncelebrated, and John Griggs is the prime example.

https://stevenhager420.wordpress.com/tag/brotherhood-of-eternal-love/

https://stevenhager420.wordpress.com/tag/brotherhood-of-eternal-love/

Griggs looked to Leary for guidance, revering the older man as a guru. At the time, the High Priest of LSD was urging everyone to start their own church. This seemed like an excellent idea to Griggs. The Brotherhood of Eternal Love, consisting of approximately thirty original members, was formally established as a tax-exempt entity in October 1966, ten days after LSD was made illegal in the state of California. The articles of incorporation announced the group's objective: "to bring to the world a greater awareness of God through the teachings of Jesus Christ, Buddha, Ramakrishna, Babaji, Paramahansa Yogananda, Mahatma Gandhi, and all true prophets and apostles of God, and to spread the love and wisdom of these great teachers to all men.... We believe this church to be the earthly instrument of God's will. We believe in the sacred right of each individual to commune with God in spirit and in truth as it is empirically revealed to him."

The Brothers settled in Laguna Beach, a small seaside resort thirty miles south of Los Angeles. It was the pure scene, an electric beach community tucked against a semicircle of sandstone hills rising twelve hundred feet above the Pacific. The majestic landscape attracted an artist colony, and the sun and waves brought surfers. John Griggs supplied a lot of LSD for a growing Freaktown where hippies danced barefoot across beaches and mountains murmuring, "Thank you, God." In this exquisite setting the Brothers employed acid as a communal sacrament, hoping eventually to obtain legal permission to expand their consciousness through chemicals in much the same way that the Indians of the Native American Church used peyote. To support their spiritual habit, they opened a storefont in Laguna Beach called Mystic Arts World, which sold health food, books, smoking paraphernalia and other accoutrements of the psychedelic counterculture. The headshop became a meeting place for hippies and freaks of every persuasion, and soon more people wanted to join the fledgling church.

Leary and his new wife, a young ex-model named Rosemary, had a standing invitation from John Griggs to visit Laguna Beach. He was greeted by the Brotherhood like a private heaven-sent prophet, and he acted the part, preaching to the group about love, peace, and enlightenment. Leary enjoyed the adulation as well as the town's mellow atmosphere. He and Rosemary rented a house near the ocean and spent much of their time dropping acid, lolling in the surf, and talking with the hippies on the beach. Leary was very conscious of his role as elder statesman of the town's burgeoning head colony. He tried to stay on good terms with everyone and never missed a chance to flash his trademark grin when he saw a policeman. --Acid Dreams

The Brothers settled in Laguna Beach, a small seaside resort thirty miles south of Los Angeles. It was the pure scene, an electric beach community tucked against a semicircle of sandstone hills rising twelve hundred feet above the Pacific. The majestic landscape attracted an artist colony, and the sun and waves brought surfers. John Griggs supplied a lot of LSD for a growing Freaktown where hippies danced barefoot across beaches and mountains murmuring, "Thank you, God." In this exquisite setting the Brothers employed acid as a communal sacrament, hoping eventually to obtain legal permission to expand their consciousness through chemicals in much the same way that the Indians of the Native American Church used peyote. To support their spiritual habit, they opened a storefont in Laguna Beach called Mystic Arts World, which sold health food, books, smoking paraphernalia and other accoutrements of the psychedelic counterculture. The headshop became a meeting place for hippies and freaks of every persuasion, and soon more people wanted to join the fledgling church.

Leary and his new wife, a young ex-model named Rosemary, had a standing invitation from John Griggs to visit Laguna Beach. He was greeted by the Brotherhood like a private heaven-sent prophet, and he acted the part, preaching to the group about love, peace, and enlightenment. Leary enjoyed the adulation as well as the town's mellow atmosphere. He and Rosemary rented a house near the ocean and spent much of their time dropping acid, lolling in the surf, and talking with the hippies on the beach. Leary was very conscious of his role as elder statesman of the town's burgeoning head colony. He tried to stay on good terms with everyone and never missed a chance to flash his trademark grin when he saw a policeman. --Acid Dreams

FATHER OF THE BROTHERHOOD

As a young man, John Griggs liked to fight. And he was good at it. Short, dark, wiry, and mean, his flair with a punch brought him to the leadership of a teenage gang called the Blue Jackets. These were the guys who parents worried about just before they started worrying about hippies—these guys were greasers, toughs, hoods. They trolled through town looking for trouble. They honed their skills by kicking cigarettes out of each others’ mouths. John and the Blue Jackets liked to jump the fence at Disneyland, track down guys from San Fernando Valley, and beat their asses. This was in Anaheim, California, where John Griggs had settled with his family as a kid, after they had come out from Oklahoma.

For all his roughness, John was still disciplined enough to earn a high school wrestling championship before he graduated in 1961. He got married that same year to a pretty, young brunette named Carol. They quickly had a couple of children together.

Soon, John left the Blue Jackets for the Street Sweepers, an infamous Anaheim “car club” whose members waged drug-fueled drag races while wearing German army helmets; they’d throw water balloons or eggs at people on the street. Somehow in all this, John managed to get a job with Anaheim Parks and Recreation as a trash collector. But he wasn’t the kind of guy who separated work from play. He smoked enormous joints while driving around town on trash details, occasionally rolling down the window to yell, “Hello! I love you!” at passing strangers.

The joys of civil service weren’t enough to keep John satisfied though. He disappeared into the California mountains for a while, earning the nickname “Farmer John” during his attempt to survive as a trapper. When he came down from the mountains, he fell back into old patterns. He became the leader of a south LA motorcycle gang; they smoked tons of grass and preyed on supermarkets.

At that point, John learned about LSD, hearing rumors that a famous Hollywood movie producer kept a large stash of it in the refrigerator of his Beverly Hills home. John and his gang arrived at the producer’s house, motorcycles roaring, armed to the teeth; they found a fancy Tinseltown dinner party in progress. Host and guests, initially disconcerted, felt great relief when they learned that all John and his gang wanted was the LSD. “Have a great trip, boys,” the producer is supposed to have said, as the men tore off with his entire stash. “Jesus,” he added. “I thought it was something serious.”

Around midnight, in the mountains above LA, John and his friends each took 1,000 micrograms of LSD— more than four times a normal dose. Hours later, as dawn broke, each man threw away his weapon, his gun, or his knife.

“This is it,” John said. “This is it.”

He and several members of the gang—plus some of his old friends from the Anaheim days—moved out of LA to share a couple of houses in Modjeska Canyon, east of the city. The group began dealing marijuana and LSD. Two things then happened: They started to talk about buying land together, and John Griggs met Timothy Leary.

John impressed Leary tremendously; Leary described him as “an incredible genius… although unschooled and unlettered he was an impressive person. He had this charisma, energy, that sparkle in his eye. He was good-natured, surfing the energy waves with a smile on his face.” The two men spoke of psychedelics as a form of sacrament; they thought groups who took psychedelics together were like congregations gathering to assert a new faith.

In October 1966, 10 days after California banned LSD, one of John’s followers (the only one without a criminal record) walked into a lawyer’s office and incorporated the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, an organization dedicated “to bring[ing] to the world a greater awareness of God through the teachings of Jesus Christ, Rama-Krishnam Babaji, Paramahansa Yogananda, Mahatma Gandhi, and all true prophets and apostles of God.” There was only one rule for joining: Eat as many psychedelic drugs as possible.

The Brotherhood operated out of a meditation room in the Mystic Arts World Store, a head shop across from a Mexican fast-foot stand in South Laguna Beach. They put the police chief of Tijuana on retainer at $30 a month; he looked the other way as Brothers purchased kilos of marijuana and headed back over the border, to sell the product in large markets like San Francisco and LA. The Brotherhood also bought LSD in bulk from suppliers in San Francisco and sold it to the large population of surfers and hippies who lived in Laguna Beach. Business boomed; John couldn’t contain his excitement over the Brothers’ success. “Hey, Uncle Tim,” he’d tell Leary over the phone, “we’ve just moved half a ton of grass and we’ve got some righteous acid.”

Leary sent his son, Jack, to check out John’s operation. Jack found the Brothers counting thousand-dollar bills by candlelight in rooms where the air was heavy with incense and marijuana smoke. Curious (and, probably, STOOOOOOOOOONNNNN-D), Jack lifted a grander off one of the stacks and poked it into the fire. The Brothers just watched. No one stopped him. Later, when Leary found out what Jack had done, he offered to replace the money. John wouldn’t hear it. “It was a great thing he did,” he said. “Very enlightening.”

That was the mood. John and his Brothers weren’t impressed with money. Getting rich wasn’t their goal: They did what they did to get psychedelics out to as many people as possible. But in the drug business in America in 1966–67, an outfit could achieve levels of naïveté like that—heroic levels of naïveté—and still make out like gangbusters. Flush with success, the Brotherhood made good on their original plan to buy land together and put a $50,000 down payment, in cash, on a 300-acre spread near Palm Springs. They dubbed the place Idyllwild Ranch.

The Brotherhood’s drug network expanded—into Afghanistan, Hawaii, the coast of England. At one point, the quality of LSD dipped, but they cut a deal with a chemist and got their product back up to snuff. John also played clean pool, with a hard-line policy against violence. No guns. When two dealers skipped off with $5,000 of Brotherhood money, John wouldn’t even let anyone go after them.

The universe repaid the Brothers with bewilderingly good karma. One night, for instance, John and a group of Brothers were heading home from a party in Hollywood, carrying close to seven kilos of marijuana in the trunk. They were dressed in beads and light robes, and they’d gotten thirsty. Someone spied an orange grove. They pulled off the highway and just went wild, climbing orange trees, eating oranges, having orange fights. A police car drove up.

Now, clearly, these men were all hippies; they were clearly driving on the highway in the early, early morning, and they were clearly stealing oranges.

But John just walked over to the cop and started explaining. No problem here, officer. Just a few thirsty guys out on the road in the wee morning hours, looking for a citrus fix.

Yeah, well, don’t let it happen again, the cop said. And drove away.

The high tide broke, as it must. Nixon became president, and he considered Timothy Leary, with whom the Brotherhood still had strong bonds of friendship and fellow feeling, to be “the most dangerous man in America.” Leary wasn’t trying to lay low, either. In 1969, he announced a bid for the California governorship against incumbent Ronald Reagan and took the media with him to his “mountain retreat,” the Brotherhood’s Idyllwild Ranch. Then, in July, a 17-year-old friend of Leary’s daughter died while visiting the ranch. Her autopsy revealed the presence of LSD in her system; homicide detectives arrested Leary—at at the ranch— for contributing to the delinquency of a minor. Soon afterward, drug cops arrived at Idyllwild, in pursuit of several Brothers who were attempting to smuggle Afghan hash into the ranch in hollowed-out surfboards. John Griggs watched through binoculars as his friends were arrested and taken away.

The Summer of Love had ended. Winter was coming. Where once John’s LSD had laced the minds of guys like Jimi Hendrix, it would soon be found altering the consciousness of the Manson Family, of the Hells Angels, of the deadly audience at Altamont.

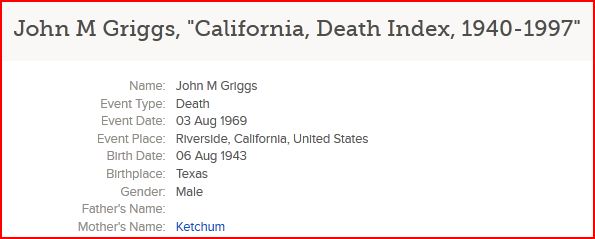

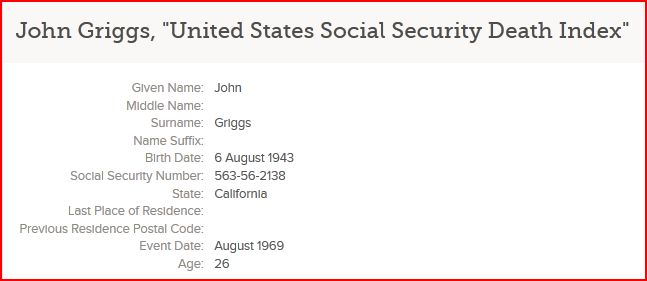

John departed just before the worst of it. On the night of August 3, 1969, he ate psilocybin crystals that a Brotherhood connection had brought back from Switzerland. In true Brotherhood fashion, he ate as much of the crystals as he could, then went into his teepee to await the results. After 20 minutes, he shouted a warning to the others: “Don’t take the psilocybin! It’s a complete overdose!” A Brother checked on him half an hour later to find John was in bad, bad shape. Still, he refused to go to the hospital. “I don’t want to go and be busted for being loaded,” he said. “It’s just between me and God, and that’s the way it’s going to be.” He grew worse and worse, and by the early morning hours his wife—that same pretty brunette John had been with since Anaheim—insisted someone take him to the hospital.

John just barely made it. He entered the emergency room in the arms of one of his Brothers, still alive. But the doors had not fully shut behind them when his body shivered, and he died.

Originally published in This Land, Vol. 4 Issue 14. July 15, 2013.

- See more at: http://thislandpress.com/07/24/2013/father-of-the-brotherhood/?read=complete#sthash.VsFt94Jp.dpuf

As a young man, John Griggs liked to fight. And he was good at it. Short, dark, wiry, and mean, his flair with a punch brought him to the leadership of a teenage gang called the Blue Jackets. These were the guys who parents worried about just before they started worrying about hippies—these guys were greasers, toughs, hoods. They trolled through town looking for trouble. They honed their skills by kicking cigarettes out of each others’ mouths. John and the Blue Jackets liked to jump the fence at Disneyland, track down guys from San Fernando Valley, and beat their asses. This was in Anaheim, California, where John Griggs had settled with his family as a kid, after they had come out from Oklahoma.

For all his roughness, John was still disciplined enough to earn a high school wrestling championship before he graduated in 1961. He got married that same year to a pretty, young brunette named Carol. They quickly had a couple of children together.

Soon, John left the Blue Jackets for the Street Sweepers, an infamous Anaheim “car club” whose members waged drug-fueled drag races while wearing German army helmets; they’d throw water balloons or eggs at people on the street. Somehow in all this, John managed to get a job with Anaheim Parks and Recreation as a trash collector. But he wasn’t the kind of guy who separated work from play. He smoked enormous joints while driving around town on trash details, occasionally rolling down the window to yell, “Hello! I love you!” at passing strangers.

The joys of civil service weren’t enough to keep John satisfied though. He disappeared into the California mountains for a while, earning the nickname “Farmer John” during his attempt to survive as a trapper. When he came down from the mountains, he fell back into old patterns. He became the leader of a south LA motorcycle gang; they smoked tons of grass and preyed on supermarkets.

At that point, John learned about LSD, hearing rumors that a famous Hollywood movie producer kept a large stash of it in the refrigerator of his Beverly Hills home. John and his gang arrived at the producer’s house, motorcycles roaring, armed to the teeth; they found a fancy Tinseltown dinner party in progress. Host and guests, initially disconcerted, felt great relief when they learned that all John and his gang wanted was the LSD. “Have a great trip, boys,” the producer is supposed to have said, as the men tore off with his entire stash. “Jesus,” he added. “I thought it was something serious.”

Around midnight, in the mountains above LA, John and his friends each took 1,000 micrograms of LSD— more than four times a normal dose. Hours later, as dawn broke, each man threw away his weapon, his gun, or his knife.

“This is it,” John said. “This is it.”

He and several members of the gang—plus some of his old friends from the Anaheim days—moved out of LA to share a couple of houses in Modjeska Canyon, east of the city. The group began dealing marijuana and LSD. Two things then happened: They started to talk about buying land together, and John Griggs met Timothy Leary.

John impressed Leary tremendously; Leary described him as “an incredible genius… although unschooled and unlettered he was an impressive person. He had this charisma, energy, that sparkle in his eye. He was good-natured, surfing the energy waves with a smile on his face.” The two men spoke of psychedelics as a form of sacrament; they thought groups who took psychedelics together were like congregations gathering to assert a new faith.

In October 1966, 10 days after California banned LSD, one of John’s followers (the only one without a criminal record) walked into a lawyer’s office and incorporated the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, an organization dedicated “to bring[ing] to the world a greater awareness of God through the teachings of Jesus Christ, Rama-Krishnam Babaji, Paramahansa Yogananda, Mahatma Gandhi, and all true prophets and apostles of God.” There was only one rule for joining: Eat as many psychedelic drugs as possible.

The Brotherhood operated out of a meditation room in the Mystic Arts World Store, a head shop across from a Mexican fast-foot stand in South Laguna Beach. They put the police chief of Tijuana on retainer at $30 a month; he looked the other way as Brothers purchased kilos of marijuana and headed back over the border, to sell the product in large markets like San Francisco and LA. The Brotherhood also bought LSD in bulk from suppliers in San Francisco and sold it to the large population of surfers and hippies who lived in Laguna Beach. Business boomed; John couldn’t contain his excitement over the Brothers’ success. “Hey, Uncle Tim,” he’d tell Leary over the phone, “we’ve just moved half a ton of grass and we’ve got some righteous acid.”

Leary sent his son, Jack, to check out John’s operation. Jack found the Brothers counting thousand-dollar bills by candlelight in rooms where the air was heavy with incense and marijuana smoke. Curious (and, probably, STOOOOOOOOOONNNNN-D), Jack lifted a grander off one of the stacks and poked it into the fire. The Brothers just watched. No one stopped him. Later, when Leary found out what Jack had done, he offered to replace the money. John wouldn’t hear it. “It was a great thing he did,” he said. “Very enlightening.”

That was the mood. John and his Brothers weren’t impressed with money. Getting rich wasn’t their goal: They did what they did to get psychedelics out to as many people as possible. But in the drug business in America in 1966–67, an outfit could achieve levels of naïveté like that—heroic levels of naïveté—and still make out like gangbusters. Flush with success, the Brotherhood made good on their original plan to buy land together and put a $50,000 down payment, in cash, on a 300-acre spread near Palm Springs. They dubbed the place Idyllwild Ranch.

The Brotherhood’s drug network expanded—into Afghanistan, Hawaii, the coast of England. At one point, the quality of LSD dipped, but they cut a deal with a chemist and got their product back up to snuff. John also played clean pool, with a hard-line policy against violence. No guns. When two dealers skipped off with $5,000 of Brotherhood money, John wouldn’t even let anyone go after them.

The universe repaid the Brothers with bewilderingly good karma. One night, for instance, John and a group of Brothers were heading home from a party in Hollywood, carrying close to seven kilos of marijuana in the trunk. They were dressed in beads and light robes, and they’d gotten thirsty. Someone spied an orange grove. They pulled off the highway and just went wild, climbing orange trees, eating oranges, having orange fights. A police car drove up.

Now, clearly, these men were all hippies; they were clearly driving on the highway in the early, early morning, and they were clearly stealing oranges.

But John just walked over to the cop and started explaining. No problem here, officer. Just a few thirsty guys out on the road in the wee morning hours, looking for a citrus fix.

Yeah, well, don’t let it happen again, the cop said. And drove away.

The high tide broke, as it must. Nixon became president, and he considered Timothy Leary, with whom the Brotherhood still had strong bonds of friendship and fellow feeling, to be “the most dangerous man in America.” Leary wasn’t trying to lay low, either. In 1969, he announced a bid for the California governorship against incumbent Ronald Reagan and took the media with him to his “mountain retreat,” the Brotherhood’s Idyllwild Ranch. Then, in July, a 17-year-old friend of Leary’s daughter died while visiting the ranch. Her autopsy revealed the presence of LSD in her system; homicide detectives arrested Leary—at at the ranch— for contributing to the delinquency of a minor. Soon afterward, drug cops arrived at Idyllwild, in pursuit of several Brothers who were attempting to smuggle Afghan hash into the ranch in hollowed-out surfboards. John Griggs watched through binoculars as his friends were arrested and taken away.

The Summer of Love had ended. Winter was coming. Where once John’s LSD had laced the minds of guys like Jimi Hendrix, it would soon be found altering the consciousness of the Manson Family, of the Hells Angels, of the deadly audience at Altamont.

John departed just before the worst of it. On the night of August 3, 1969, he ate psilocybin crystals that a Brotherhood connection had brought back from Switzerland. In true Brotherhood fashion, he ate as much of the crystals as he could, then went into his teepee to await the results. After 20 minutes, he shouted a warning to the others: “Don’t take the psilocybin! It’s a complete overdose!” A Brother checked on him half an hour later to find John was in bad, bad shape. Still, he refused to go to the hospital. “I don’t want to go and be busted for being loaded,” he said. “It’s just between me and God, and that’s the way it’s going to be.” He grew worse and worse, and by the early morning hours his wife—that same pretty brunette John had been with since Anaheim—insisted someone take him to the hospital.

John just barely made it. He entered the emergency room in the arms of one of his Brothers, still alive. But the doors had not fully shut behind them when his body shivered, and he died.

Originally published in This Land, Vol. 4 Issue 14. July 15, 2013.

- See more at: http://thislandpress.com/07/24/2013/father-of-the-brotherhood/?read=complete#sthash.VsFt94Jp.dpuf

Orange Sunshine

The Brotherhood of Eternal Love and Its Quest to Spread Peace, Love, and Acid to the WorldBy Nicholas Schou(Thomas Dunne/St. Martin's; 306 pages; $24.99)

"Don't take the brown acid" was the famous warning issued about a bad batch of LSD from the stage at the Woodstock Festival in 1969. But meanwhile, some shadowy but influential West Coasters were counseling everyone to try the orange stuff.

Orange Sunshine was a "brand" of LSD made and marketed by a band of initially idealistic young men operating out of Laguna Beach, the bucolic village ironically nestled in Orange County. Calling themselves the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, they were acid evangelists who soon became known as a "hippie mafia."

The Brotherhood's story is "the most surreal saga of the 1960s that has never been told," writes journalist Nicholas Schou, whose new book, "Orange Sunshine," is as close to an "authorized" story as there's likely to be. Much of it reads more like fiction than history.

If there was a key founder of the Brotherhood, it was John Griggs, whom Timothy Leary would call "the holiest man ever to live in this country." Griggs and a few friends began as working-class petty criminals who heard about a new drug called LSD, stole some at gunpoint from a Hollywood producer, and soon were apostles of psychedelic-induced "ego death," wherein one "realizes the insignificance of his or her petty, worldly concerns and feels for the first time a powerful and humbling connection to a greater life force in the universe."

Thus Griggs felt that if enough people took enough acid, "they could create a utopian society that would serve as a demonstration to the entire world of the healing powers of LSD." Their goal: use market forces to make LSD cheap by flooding the nation with it. In 1966 the Brotherhood drew up a legal charter, moved to Laguna Beach in search of nice beaches and pretty girls, and "helped usher in a flowering hippie scene that established the city as a Southern California version of Haight-Ashbury."

In their heyday, "Brothers" smuggled surfboards inlaid with LSD and hash worldwide. Mexican officials were paid off to allow tons of pot to cross the border. A hash-packed yacht was sailed to Hawaii by stoned non-sailors. Jimi Hendrix was enticed to make an incoherent film, and even the famously stoned guitar god found the Brothers too weird. Leary was busted in Laguna Beach, but broken out of jail using Brotherhood of Eternal Love money funneled to the Weather Underground and Black Panthers.

But soon things went sour. "Cocaine, and the greed and paranoia that came with it destroyed whatever was genuine in the Brotherhood's idealistic, spiritual origins," writes Schou. Griggs had already died of a psilocybin overdose, and rougher Brothers prevailed. Rip-offs and violence ensued. It all culminated in a 1972 bust that "yielded 53 people and two and half tons of hash, thirty gallons of hashish oil, and 1.5 million tablets of Orange Sunshine."

"The Brotherhood's dream of turning on the world had been deferred," concludes Schou. But dreams die hard, and Schou's interviews with surviving Brothers, some doing well, some penniless, illustrate the thin line between dream and delusion. "We ushered in the age we are in now, which reflects a much more open-minded, open-hearted and spiritually inspired world," reflects one Brother, who must live a very isolated life.

The Brotherhood of Eternal Love and Its Quest to Spread Peace, Love, and Acid to the WorldBy Nicholas Schou(Thomas Dunne/St. Martin's; 306 pages; $24.99)

"Don't take the brown acid" was the famous warning issued about a bad batch of LSD from the stage at the Woodstock Festival in 1969. But meanwhile, some shadowy but influential West Coasters were counseling everyone to try the orange stuff.

Orange Sunshine was a "brand" of LSD made and marketed by a band of initially idealistic young men operating out of Laguna Beach, the bucolic village ironically nestled in Orange County. Calling themselves the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, they were acid evangelists who soon became known as a "hippie mafia."

The Brotherhood's story is "the most surreal saga of the 1960s that has never been told," writes journalist Nicholas Schou, whose new book, "Orange Sunshine," is as close to an "authorized" story as there's likely to be. Much of it reads more like fiction than history.

If there was a key founder of the Brotherhood, it was John Griggs, whom Timothy Leary would call "the holiest man ever to live in this country." Griggs and a few friends began as working-class petty criminals who heard about a new drug called LSD, stole some at gunpoint from a Hollywood producer, and soon were apostles of psychedelic-induced "ego death," wherein one "realizes the insignificance of his or her petty, worldly concerns and feels for the first time a powerful and humbling connection to a greater life force in the universe."

Thus Griggs felt that if enough people took enough acid, "they could create a utopian society that would serve as a demonstration to the entire world of the healing powers of LSD." Their goal: use market forces to make LSD cheap by flooding the nation with it. In 1966 the Brotherhood drew up a legal charter, moved to Laguna Beach in search of nice beaches and pretty girls, and "helped usher in a flowering hippie scene that established the city as a Southern California version of Haight-Ashbury."

In their heyday, "Brothers" smuggled surfboards inlaid with LSD and hash worldwide. Mexican officials were paid off to allow tons of pot to cross the border. A hash-packed yacht was sailed to Hawaii by stoned non-sailors. Jimi Hendrix was enticed to make an incoherent film, and even the famously stoned guitar god found the Brothers too weird. Leary was busted in Laguna Beach, but broken out of jail using Brotherhood of Eternal Love money funneled to the Weather Underground and Black Panthers.

But soon things went sour. "Cocaine, and the greed and paranoia that came with it destroyed whatever was genuine in the Brotherhood's idealistic, spiritual origins," writes Schou. Griggs had already died of a psilocybin overdose, and rougher Brothers prevailed. Rip-offs and violence ensued. It all culminated in a 1972 bust that "yielded 53 people and two and half tons of hash, thirty gallons of hashish oil, and 1.5 million tablets of Orange Sunshine."

"The Brotherhood's dream of turning on the world had been deferred," concludes Schou. But dreams die hard, and Schou's interviews with surviving Brothers, some doing well, some penniless, illustrate the thin line between dream and delusion. "We ushered in the age we are in now, which reflects a much more open-minded, open-hearted and spiritually inspired world," reflects one Brother, who must live a very isolated life.

Excerpt 1.

The Farmer

N THE MID-1950s, Anaheim, California, a smog-choked working-class town fifteen miles from the nearest beach, was bursting with recent Mexican immigrants and a mass migration of blue-collar white Americans who had fled south from the wave of black families who began to move into Los Angeles suburbs like Watts and Compton after the Second World War.

A century after it was founded by German immigrants as a farming community in 1857, Anaheim's boundless orange groves were quickly being devoured by factories and suburban tract. In 1955, the city's most famous feature, the Disneyland Theme Park, opened its doors and, at about that time -- the exact date is unclear a tough young Okie with an awkward stutter arrived with his family to find the American dream.

Long before he became Timothy Leary's self-described spiritual guru and the leader of the secretive group of drug smugglers who literally provided the fuel for Americas psychedelic revolution, back when John Griggs was still in junior high school, his classmates knew him as an occasionally mean-spirited badass prone to picking fights. He was short but wiry and muscular a champion wrestler, to boot- and wore his dark, fine hair slicked back from his forehead in a jaunty pompadour. His piecing blue eyes seemed to be pulled downward by some force beyond gravity, giving his face a somber, almost tragic expression, even when accompanied by his perpetually crooked and mischievous-seeming shit-eating grin.

John Griggss Graduation Photo, Anaheim High School, 1961.

When Griggs spoke, he tended to stutter for the first few syllables, a speech impediment that might have been amplified by the amphetamine pills he was known to pop like candy as a teenager. He spoke fast, and the stutter would disappear a few words into each sentence. He had a quick wit and an uncanny ability to size people up. Few people who knew him ever saw Griggs actually fight. He didn't have to use his fists. Instead, Griggs would walk up to a guy he didnt like, usually someone much more muscular or who had a reputation as a bully, and start hurling insults and threats at his rival. If the guy didn't back off, Griggss buddies would suddenly appear out of nowhere, jump in, and start kicking the shit out of the offending party.

Robert Ackerly, a tall, lanky kid with stringy dark hair and an impudent smirk that never left his face, befriended Griggs at Anaheim High School. Ackerly hung out with a trio of brothers, Tommy, JC, and Freddy Tunnell, whose parents were friends with the Griggs family in Oklahoma and who had moved west together. Ackerly was a few years younger than Griggs but best friends with Tommy Tunnell, who, like his brothers, and Griggs, for that matter, was a rebellious, unruly jock.

Tunnell introduced Ackerly to Griggs at a party in 1958. Griggs and the rest of the wrestling team, decked out in blue nylon jackets with varsity letters, were drunk and angry. Griggs boasted loudly to Ackerly that they planned to crash another party and beat the shit out of the captain of a wrestling team from a rival high school. Griggs called his coterie of fellow wrestlers the Blue Jackets.

In Ackerly's telling, the gang represents the earliest incarnation of Griggss organizing abilities that would ultimately create the legendary Brotherhood of Eternal Love.

Griggs was already dating an attractive young brunette from Long Beach, Carol Horan, whom he would marry in 1961, the year he graduated from high school, a few classes behind Bobby Hatfield, half of the legendary “blue-eyed soul” duo the Righteous Brothers, whose early-1960s hits included “Unchained Melody” and “You've Lost That Loving Feeling.”

By then, Griggs had left the Blue Jackets behind and taken over the Street Sweepers, an infamous Anaheim car club; its members, who met at a Mexican grease joint called the Bean Hut, bounced back and forth between school and juvenile hall, staging impromptu drag races and cruising around in German army helmets, drunk or high on speed or pot, throwing water balloons and eggs at anyone they didnt know or didn't like.

Ackerly was something of a badass himself, but not nearly so much as his older brother Dick, a barroom brawler so notorious that fighters from as far away as Boston and Chicago would come to town specifically hoping to break his nose. Dick taught Ackerly how to box. His first fight took place just three days after he moved to Anaheim from Los Angeles in 1956, when he was just twelve years old, a freshman at Fremont Junior High School. Someone who didn't like the way Ackerly was looking at his girlfriend grabbed him by the neck and started kicking him in the nuts until his brother Dick ended the brawl by punching his attacker in the head.

“In those days it was pure fisticuffs,” Ackerly recalls. “There was no peace and love going on at that time. It was ‘Don't look at me. What are you looking at? You wanna fight?”Through his friendship with Tunnell, Ackerly began hanging out with Griggs and quickly became part of the latters entourage of street fighters. Once, at another party, they were standing in front of someones house when Griggs saw a group of older, bigger guys sitting in their car. He walked over and jabbed his finger in the face of the driver. “Get out of that fucking car,” Griggs barked. “I am going to beat your fucking ass! I am going to scratch your fucking eyes out and bite your fucking nose off, motherfucker.”

Tunnell and Ackerly stood by ready to start throwing punches. But as Griggs reached through the window to pull one of the passengers out of the car, the terrified teenagers sped off.Before long, Ackerly, Tunnell, and several of their classmates were following Griggs all over Anaheim looking for fights. Sometimes they just fought among themselves, practicing their skills by kicking cigarettes out of each others mouths, but usually they looked for anyone from outside Anaheim who was stupid enough to wander into their town.

“We'd go pile into a car and jump over the fence into Disneyland, then look for guys from the [San Fernando] Valley so we could kick their asses, because this was our turf,” Ackerly says. “We were Anaheim guys, and Johnny was the boss. Johnny took over everything. People started calling him ‘the Farmer because he gathered everyone around him like Johnny Appleseed. He just grew followers; everyone followed John.”

“John was never anyone I would follow,” insists Edward Padilla, who also befriended Griggs in high school.

“He was a sneaky, manipulative little bastard. He would usually pick a fight with someone bigger, and when the fight started, everyone would start coming out of the woodwork.”

Padilla's family moved to Orange County in the early 1950s from South Central Los Angeles. Although his mother was of German-Irish extraction, Padilla's dad, a construction contractor, was half black and half Native American and commuted back to Los Angeles for work, because, as a nonwhite, he couldnt get a single job in Orange County. “I had dark skin,” Padilla says. “Because I wasn't Mexican or white, I wasn't enough of any one color to be part of either crowd.” When he turned sixteen, Padilla, like everyone else he knew, went to Disneyland to apply for a summer job. “I was the only one not to get hired,” he says. “Anaheim was a different world back then.”

In school, Padilla established himself as the class troublemaker. One day his teacher told him to shut up and sit down. Padilla ignored him, so the teacher grabbed him by the throat and slammed him into his seat. Padilla kicked the teacher in the balls. The teacher went home for the day to nurse his wounds and Padilla ended up being expelled from Anaheim's public education system. He attended St. Boniface Parish School, a privately run Catholic institution, where he scraped with an older student who made the mistake of insulting Padillas mother.

“What are you looking at?” the kid asked. “Fuck you,” Padilla answered. “Ill fuck your mother,” the kid responded. Padilla punched him in the face until the kid was lying on the floor unconscious. “I broke his head open, so they sent me to juvenile hall.”After he got out, Padilla attended Servite High School, an allboys facility full of public school rejects taught by robe-wearing priests. “We were some rough guys,” recalls Padilla, who by now had bulked up into a muscular athlete. During his sophomore year, Padilla insulted one of his teachers, a former professional football player who promptly slapped him across the face.

“You slap like a girl,” Padilla observed. The teacher slapped him again, hard enough to send Padilla reeling from his seat. He picked up his desk and swung it at the teacher. That stunt sent Padilla to another private school in Downey, where he joined the football team and resumed fighting. When he attacked a fellow football player who wound up in the hospital with cracked cheekbones and his jaw wired together, Padilla found himself again expelled and sent back to Anaheim.

At a sock hop during his first year back at Anaheim High School, Padilla danced with a girl who happened to be dating a friend of Griggss named Mike Bias. The dance ended and Bias and about ten other angry-looking guys including John Griggs walked up to Padilla. “You fucked up,” Griggs announced. “You dont mess with our girls. Were going to kick your ass.” Padilla continued dancing with the girl. When the sock hop ended, he went outside, fists clenched, ready to rumble. Nobody was there. “I was glad,” he says. “Dont get me wrong. Ten to one didnt sound fun.”

The next day, however, Griggs approached Padilla with an olive branch, telling him that the rest of his gang was planning to ambush him. A few weeks later, Griggs told Padilla the fight would happen that evening in an orange grove outside of town. He drove Padilla to the location and pumped him with information about who was going to try to take him down. He warned Padilla to watch out for a sucker puncher named Franco who planned to wait until Padilla had been worn down fighting other contenders before he stepped in to finish him off.“

I rode out to this grassy meadow in the middle of this orange grove in Johns 1938 Cadillac,” Padilla recalls. “There were probably fifty kids there, mostly guys, standing in a circle.” Padilla cracked his knuckles and readied himself. Without warning, a couple of football players rushed him simultaneously. One of them charged into Padilla, sending him flying backward. He leaned over and sank his teeth into the guys back. As Padilla pushed him away, the next jock came flying forward.

Suddenly, one of Griggs's friends, who unbeknownst to Padilla had been appointed by Griggs to intervene, stepped forward to protect him. “Little by little, even though we had different agendas, I realized I was covered in a strange way,” Padilla says. “Johnny was always trying to have a gang of guys and that was the opposite of me. I was a loner, but John needed a lot of people to accomplish what he wanted. He was a masterful politician. He had a gift of gab, and people followed John.”

Padilla and Griggs were both fans of The Untouchables, a television show broadcast on ABC every Thursday night from 1959 to 1963. Based on the memoir by legendary G-man Eliot Ness, the show fictionalized his pursuit of the notorious Chicago mob boss Al Capone. To Padilla, it seemed to provide free lessons in how to operate a successful criminal enterprise. “Capone and his gang were so successful because they didnt use violence to achieve their aims,” he says. “I watched that show religiously, every Thursday night,” Padilla says.

“I wanted to be a successful criminal. My product was going to be pot and pills and I was going to run all of Orange County.” Inspired by the shows character Arnold “Spatz” Vincent, Padilla went to a thrift store and bought a pair of spats and black and white wing-tipped shoes, slacks, a button-down vest, and a Gant shirt with a button-down collar. Griggs and his crew were dressing up like their favorite gangsters as well. Griggs thought of himself as Capone, and his 1938 Cadillac testified to his admiration for the mob boss.

Eddie Padilla;s dream of becoming Orange County's biggest pot dealer was deferred by several jail stints, everything from indecent exposure to dealing drugs to assaulting a cop with a wrist pin, a steel bar that when gripped in a tight fist could land a deadly punch. His lawyer persuaded a judge to send him to Atascadero, a hospital for the criminally insane, where Padilla spent the next eighteen months. By now, he was eighteen years old and had knife scars up and down his arms and was missing several front teeth.

Padilla's stint in the loony bin convinced him to leave street fighting behind him. He married his high school sweetheart and rented an apartment with the money he was making selling pot, cheap weed smuggled across the border from Mexico. In those days, marijuana was divided into “lids” which referred to a whole can of Prince Albert brand rolling tobacco, and “fingers,” which was a fingers width of pot inside the can.

Soon, Padilla wasn't just dealing, he was supplying pot to other dealers, like Jack “Dark Cloud” Harrington, a street fighter from Westminster. One night, Padilla went over to Harrington's house to see if he needed any more pot to sell. Sitting in the living room was his old friend John Griggs, whom Padilla hadn't seen since high school.

Griggs was now married, working in the nearby oil fields of Yorba Linda and, like Padilla, dealing a lot of pot.“I became the biggest dealer in Anaheim, and maybe Garden Grove,” Padilla says. “I had a lot of customers and went around meticulously turning people on to pot. I believed in pot.”

One day, Padilla's pot supplier introduced him to someone who was bringing kilograms of weed across the border every weekend. Now Padilla could sell half pounds and quarter pounds of marijuana at a pop. He went back to all the people he knew, turning them on to pot and looking for the next adventure. “I was twenty years old and figured I needed to go down to Mexico and do something worthy,” he says.

“Being an adrenaline junkie, smuggling was appealing to me. I couldn't wait.”

While Padilla and Griggs conspired to dominate Orange Countys drug trade, Robert Ackerly had taken to hanging out on the beach, drinking beer, smoking pot, and surfing. He and Tommy Tunnell passed most of their time playing hooky from school and hitting the waves down in Huntington Beach. One night, police discovered Ackerly having sex with a runaway girl on the sand. “They said it was immoral for us to have our clothes off at the beach,” he says. “This was Orange County, so I did three months in juvenile hall.”

Shortly after getting out, Ackerly and Tunnell went to a movie in Los Angeles. After the show, someone looked at him the wrong way. Words were exchanged and Ackerly punched the man until blood poured from his mouth and ears. As Ackerly politely explained to the theater manager that the other guy started the fight, the police and an ambulance arrived. The cops arrested him and took him back to jail. “Because of my record, they told me I was going into the service tomorrow. It was either that or stay in jail.”The following morning,

Ackerly volunteered for the air force, then the army and marines, but was rejected each time because of his criminal record. Just when he thought his only option was more jail time, the navy accepted him. “I got busted for getting in a fight and fucking a girl on the beach. They said, ‘Fucking and fighting? You came to the right place, buddy.” After joining the navy, Ackerly sailed to the South China Sea, where he served as a navigator on the Mauna Koa, an ammunition ship. For three years, he stockpiled ammunition in the Philippines and after the war started in Vietnam, he sailed to the Tonkin Gulf.

Ackerly never saw any actual combat, other than the random fight with his shipmates and the time he crossed paths with a group of marines in Cam Ranh Bay, who jumped him and left him bloodied, with two black eyes.Ackerly visited his first opium den in Hong Kong. He met a group of mercenaries there who said they'd just returned from Burmas Shan Mountains part of the “Iron Triangle” of poppy cultivation where Chinese warlords protected the largest source of heroin in the world.

The mercenaries gave Ackerly his first hit of heroin, which he says he refused to inject, but sniffed, an experience that rewarded him with a several-hours-long, Viagra-like erection that he put to use at an adjacent whorehouse. On another leave, Ackerly returned to Orange County, looking for Tommy Tunnell and John Griggs, who had moved next door to a heroin addict named Joe Buffalo (true name, believe it or not), a fearsome fighter who had already done prison time.

While Ackerly was overseas, Griggs and Tunnell had fallen in with Buffalo and become heroin addicts, themselves. “John called me a baby killer for being in the navy,” Ackerly says. “Him and his buddies were carrying guns and dressing like gangsters, wearing brimmed hats and all this shit.”

Tunnell told Ackerly that he and Griggs had just learned about a drug more powerful and much stronger than heroin: LSD. Griggs was intrigued by the rumors, and when he found out that a flamboyant Hollywood film producer who lived in a mansion in the hills kept a big jar of it on top of his refrigerator, he set out to get it.

According to Eddie Padilla, Griggs dropped by one day, told him of his plan, and asked to borrow a gun for the mission. “I said, ‘No gun,” Padilla recalls. “‘Just walk in and slap somebody and tell them you want the acid and theyll give it to you, guaranteed.” Griggs shook his head and left. He later told Padilla that Tommys brother, JC Tunnell, found him a gun. “The two of them went up there with ski masks and stole that acid. It was still legal, but thats how John got his acid.”

That night, Griggs, Tunnell, and Buffalo dressed up in their brimmed gangster hats, donned overcoats, and armed themselves with handguns and shotguns. They drove up to the mansion, barged into a party that was taking place, and stuck their weapons in the face of the hapless producer, who promptly handed over his stash of LSD.

Chuck Mundell, an avid surfer from Hermosa Beach who hung out with Griggs at the Bean Hut and taught him how to surf, had fallen out of touch after Griggs got married and moved next door to Joe Buffalo.

“I would go to Hawaii off and on, and only saw John occasionally,” Mundell recalls. “Surfing is all I did in those days. John was shooting heroin with Joe, dealing marijuana, and committing burglaries. After he and Joe and Tunnell robbed those people in Hollywood, they brought back that LSD and took the stuff. They must have had a pretty wild experience, because John told me they went to the guy and gave it back to him.

John apologized to him and said he wanted to know where he could get more.”Griggs also confessed to Mundell that his young son, Jerry, had somehow swallowed part of a vial of the acid hed stolen at gunpoint. “John told me that Jerry got hold of that blue liquid,” Mundell says. “He was on his rocking horse all night long. He took a whole lot of stuff. He was a little kid, real little, and that was his first trip. He went far.”

Shortly after he discovered LSD, Griggs contracted hepatitis thanks to his heroin habit. He called Mundell to his hospital bed, and claimed to have just undergone a near-death experience that he told Mundell had everything to do with the acid hed stolen at gunpoint: a life-altering vision that Timothy Leary and other scholars of psychedelic drug phenomena refer to as an “ego-death” trip, where the initiate realizes the insignificance of his or her petty, worldly concerns and feels for the first time a powerful and humbling connection to a greater life force in the universe.

Mundell had already dropped acid, but he hadnt experienced anything like what Griggs described. “Something had happened to John in that hospital, and I dont know what it was,” Mundell says. “He asked me to come to the hospital and take Christ into my heart with him. I went up there and said, ‘To me, God is something that is inconceivable, so what do you mean? And he said, ‘Come with me, and Ill show you what I mean.”

As soon as Griggs recovered from his illness, he invited Mundell to drop acid with him. For several hours, Mundell sat in Griggss living room, watching what he can only describe as a “color wheel” that rotated in the air. He went into another room, still seeing the wheel, and asked Griggs to try to read his mind. Griggs described exactly the same wheel.

“We were communicating,” he said. “It was real, psychic. We went outside and sat in the car and the windshield just melted. The next time I dropped acid, I was with my brother on the beach and there was only one little cloud in the sky and it turned into the face of Jesus Christ. My brother had tears in his eyes and the sky looked like a golden ocean with perfect waves, like heaven.”

Mundell might have been the first person Griggs invited to join with him in an LSD trip, but he certainly wouldn't be the last. Soon Griggs would recruit everyone he knew—surfers, street fighters, pot dealers and petty crooks into a tribe of people who viewed acid as a sacrament, a window into God itself, a key to unlock what Aldous Huxley famously called the “doors of perception.”

Griggs told anyone who would listen that, through acid, they could create a utopian society that would serve as a demonstration to the entire world of the healing powers of LSD. Although Mundell for one wasn't sure that Griggs would be able to convince the world that acid was the living incarnation of God, he knew even before he first dropped acid with Griggs, as he watched his friend still clinging to life in his hospital bed, that Griggs would carry out his plan to the finish.

That realization had occurred just as Mundell stood ready to leave Griggss hospital room, when a couple of Griggss heroin buddies arrived to give him his next fix. “John told them to leave,” Mundell says. “I believe he was told by the higher power that he was going to do this thing turn people on to God because he was the person who had the direction to keep it all together; and we were all just part of it.”

As Mundell prepared to leave the hospital room, Griggs told him to wait a moment. He closed his eyes and smiled. For a moment, Mundell thought his friend was about to succumb to his heroin-induced hepatitis. But Griggs wasn't dead yet. His eyes were filled with love and a strange and mystic energy. He was facing Mundell as he spoke, but looking right through him. “Its God,” Griggs exclaimed.

“Its God.”Bobbing in the calm water of the channel about a hundred yards from the protected side of the jetty was the palest redneck cracker Travis Ashbrook had ever seen. The man was stretched back in an inner tube, his feet splayed out, with one hand resting behind his crew-cut head and the other gripping a Budweiser. On the other side of the jetty, twenty-foot waves crashed into the southernmost shore of Newport Beach's Balboa Peninsula, an infamous surf spot locals call the Wedge. Hundreds of people from all over Orange County had gathered at the Wedge on this sunny summer day in 1965 to watch their foolhardy friends try to ride the spectacularly violent waves, which broke too close to shore for regular surfboards --only bodyboards could handle this quick action.

Ashbrook stood on the jetty, watching bodyboarders being tossed willy-nilly in the water. Suddenly he recognized another spectator: John Griggs, the notorious leader of Anaheims Street Sweepers. “John was a legend,” says Ashbrook, who grew up in Rossmoor, a middle-class suburb a few towns away from Anaheim. “The Street Sweepers were a car club, but nowadays theyd be called a gang.

They liked to crash parties and start fights on weekend nights. They would always send John in because he was the littlest guy and someone would hassle him and then the big guys would jump in.”As Ashbrook started walking back to the beach, Griggs and his friends began hurling rocks at the pale man on the inner tube who was drifting peacefully in the channel. “This guy was mayonnaise white, what we called a ‘flatlander, a hick, some guy from godknows-where, but who definitely wasnt from the beach and wasn't from Southern California,” Ashbrook recalls.

Instead of trying to paddle away, the man ditched his beer, jumped out of the inner tube, and swam over to the jetty, rocks still pelting the water all around him. Griggs and his pals continued to hurl insults. “This guy was all by himself, but he came up to John, and John beat him up. John was real quick. That didn't take but a minute.”Ashbrook was impressed that Griggs handled the fight on his own, without any backup, even though he had friends standing nearby.

“I wasn't a fighter, but everyone did it now and then, because you didnt want to get branded a chicken,” he says. “Its better to start a fight and lose than not fight. There were only a couple of us surfers in school, so we were outcasts, and people tried to jump me and cut my hair.” Ever since junior high school, when Ashbrook started surfing and growing his hair down below his shoulders, he;d had to fight every once in a while because he stood out. “I started surfing just as I was getting ready to go to high school, and nothing mattered after that.”

Ashbrook surfed all up and down the coast, all the way north to Santa Cruz and down to Baja California, but generally it was the Trestles, a beautiful stretch of beach between San Clemente and the marine base at Camp Pendleton, widely believed to be a world-class surf spot. He repaired his boards in his mothers garage and then began shaping new ones for himself and his friends.

By the time he graduated from high school in 1963 hed rented a storefront in Sunset Beach where he made and sold surfboards and surfing gear. He also worked part-time at the Golden Bear, a trendy nightclub in Huntington Beach, and was a regular at Balboas Rendezvous Ballroom, where Dick Dale and the Del-Tones—whose hit 1963 instrumental “Miserlou” later achieved fame in Quentin Tarantino's Pulp Fiction played every weekend.

A fat guy nicknamed the Buddha whom Ashbrook met at the Rendezvous gave Ashbrook his first joint. “He hung out in Seal Beach and had this big old van and all these chicks with him all the time,” Ashbrook recalls. “I didnt like having to pay for pot. It cost ten dollars an ounce in those days, which was a lot of money.” Ashbrook surfed the beaches near Tijuana, where a kilogram of weed could be had for twenty dollars. A Mexican dishwasher who worked at the Golden Bear told Ashbrook he knew pot dealers in Tijuana, and agreed to travel south with him to arrange a deal.

The dishwasher drove Ashbrook across the border, and once they reached Tijuana, they circled around town looking for cabdrivers. “We cruised around for a while and a cabdriver scored us a kilo of weed in a big brown paper bag,” he says. Then Ashbrook and his friend drove east to Tecate, a border town in the mountains about an hours drive from Tijuana.In those days, there were no fences to demarcate remote stretches of the U.S.-Mexican border between Tijuana and Mexicali.

The crossing at Tecate consisted of a tiny hut that was unguarded at night, with only a padlocked chain stretching across the road. Ashbrook and his friend drove up to the Mexican side of the border, parked their car, and crept out about a hundred yards to the American side of the road, found a culvert, and threw the bag of weed into the ditch. Then they drove back to Tijuana, crossed the border, headed east and drove back south to Tecate, down to the culvert, grabbed the weed, and drove home.

In the next few weeks, Ashbrook repeated the journey, smuggling a few kilograms at a time from Mexico to Orange County simply by tossing a bag of weed over a fence in the middle of the desert.After he broke up with his girlfriend, she called the cops and told them about his smuggling activity. “They barged right in without a warrant,” he says. “They went right to my bedroom, found a couple of baggies, and busted me. I was in jail for eighteen days until my mom bailed me out. I ended up getting three years of probation because I was attending Orange Coast College and I had my own surf shop.”

The downside of being released so quickly, Ashbrook says, was that many of his friends assumed he was a snitch. How else could one explain his lenient treatment? But one person who didnt seem to harbor any suspicions was Griggs. After bumping into each other at the Wedge, the pair struck up a friendship. Although theyd never spoken so much as a word to each other in high school, Griggs was impressed with Ashbrooks status as one of the best surfers in Orange County. They were also both rapidly working their way up the ladder in the county's marijuana trade— and were even being supplied by the same dealer.

One day, Ashbrook gave the dealer money for a kilogram of pot. When he went to pick up his drugs, the dealer told him all he had available at the moment was LSD. Ashbrook had read a few books about psychedelics and was curious to try it. He dropped his first acid that summer after reading The Psychedelic Experience by Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert, and Ralph Metzner. According to Metzner, he and Leary got the idea to write The Psychedelic Experience during a conversation they had while in Mexico. Leary had spoken with Aldous Huxley, the author of Brave New World and a proponent of LSD who would drop acid on his deathbed, and Huxley had told him that the world needed a manual for taking psychedelics.

Leary told Metzner that the manual should be based on The Tibetan Book of the Dead. “Tim said, ‘Lets take the text of the Tibetans and strip the particular cultural and religious language and rewrite it as a manual,” Metzner now recalls. “We started working on that and tested it out, did sessions with each other, testing the model. We were exploring the whole idea of arranging a setting to enhance spiritual experiences for healthy people, not patients or criminals, but ourselves.”“That book was all mumbo jumbo to me,” says Ashbrook. “It scared the hell out of me. There was a period of time when I refused to read it because it was just too far out.

When I read that book, strange things started happening to me, intense things, bad trips. The problem with psychedelics is that the vessel can only take so much, and as your inner vessel grows, it can obtain more of the light, but if your ego is still the main focus of your life, that light will black you out and it will kill you.” Ashbrook had more important things to attend to that summer than losing his ego: his surf business and his growing side career as a pot dealer. He was also in love, and in August 1965, he got married.

Ashbrook's pot dealer attended the wedding and told Ashbrook to stop by Griggs's house in Garden Grove.“He told me that John had a present for me,” he recalls. “So on the way to our honeymoon, we stopped by. John broke out a bottle of champagne and gave me a shoebox full of a pound of weed. It was totally clean, ready to roll, and we didnt even know each other that well, but there was some kind of connection, and from there our friendship grew.” Underlying their growing friendship was Griggss amazement that Ashbrook had taken LSD but, unlike him, hadnt experienced a profoundly spiritual sense of self-awareness. He promised Ashbrook that if they dropped acid together, he'd see the light soon enough.

“Maybe I was some kind of challenge to him,” Ashbrook says. “His gangster days were behind him. He had already experienced his personal ego death, his meeting with the forces that be, and hed reconciled his path. He was sure of his mission and that I was part of it.”Unlike Ashbrook, Eddie Padilla had yet to realize he was part of John Griggss mission. The first acid he dropped was a vial of clear liquid hed obtained from a friend. “I used to take a handful of reds--speed--to hallucinate,” he says. “It was entertaining, so I couldnt wait to try acid, because everyone said it made you hallucinate.”

After drinking a vials worth of the liquid, he got in his car and drove back to his apartment along Lincoln Avenue. “I had been on Lincoln Avenue ten thousand times in my life, but it was like I had never been there before,” he says. “It was incredibly clear. I could see all these traffic lights down the road, off into infinity.” Somehow, Padilla managed to stay focused enough to drive to The Stables, Anaheims rowdiest dive bar, where he encountered Griggss friends, Gordon Sexton, Mark Stanton, and Mike Randall. “As soon as I showed up, I just started cracking up laughing. I rolled out of the door into the alley.” Everyone at the bar had already dropped acid and knew exactly what was going through Padillas mind. “They were all laughing,” Padilla says. “You took the acid! You took the acid.”

A few days later, Padilla drove over to his friend Jack Harrington's house and took another dose of LSD. He and Harrington went back to the bar. Padilla recalls that what was on his mind had little to do with spirituality. “I thought I could see through all the girls clothes,” he says. “And the band that was playing had this energy. I could feel the energy. It was like being in kindergarten.”

When Padilla dropped Harrington off at his house, Griggs came walking up to him. “Its all about God, man. Its all about the Bible. Thats where its at, man!” he declared. Padilla could hardly believe his ears. “What the fuck is he talking about?” he asked himself. “Holy crap. John Griggs talking about the Bible. This is fucking absurd.”

Padilla didnt think much of LSD at the time. It seemed like a fun trip, but he was much more interested in popping pills. Besides dealing pot, he was busy supplying amphetamine tablets to Anaheim biker gangs like the Mongols. “I was an extremely dangerous person,” he says. “Just a really rotten individual. I wouldnt piss on my own head if I were on fire. I had no scruples. I had guns. Id stabbed people in self-defense, and I wouldnt hesitate to shoot someone in the shoulder just to let it be known who I was.” Hed been married for only a year, but his wife had already left him. “She had good reason to leave me,” he allows. “I was sleeping with five other women in my apartment complex.”

Padilla asked a couple of mutual friends what had happened to Griggs. “Oh, he took some acid,” they explained. “Oh, my god,” Padilla thought. “There might be something to this.” Later that week, Padilla joined Griggs and his wife, Harrington, a firefighter named Lyle “Lyncho” German, and several other friends, in an acid-dropping session at Mount Palomar, a 6,100-foot peak in northern San Diego County. Their caravan of cars drove up the mountain at sunrise. Padilla began to feel uncomfortable. “I was a city boy and had never been to the mountains,” he says. “I hated the snow. I never went hiking in the hills.” Wanting to get back to town as soon as possible, Padilla insisted they drop their acid immediately. “We each took two capsules of white powder and kept driving up the mountain along this windy road.

Suddenly I felt this pressure to lean back. It was really different than anything I had experienced before.”As Padilla stretched back in his seat, feeling a tremendous weight upon his body, he closed his eyes. Someone read aloud from The Psychedelic Experience: “That which is called ego death is coming to you. You are about to come face to face with the clear light of reality.”

Padilla says he lost consciousness, and when he awoke, he found himself alone in a forest, surrounded by majestic trees. “Thats when I realized I was dead,” Padilla says. He wandered into the woods and encountered Griggs and the rest of the group, sitting in a circle. “I thought they were all dead, and we were all in heaven.”Padilla felt too weak to stand up. “Lyncho helped me back to the car and told me to lie down, so I laid down in the backseat and everything just really went off,” he says. “The light came on in my head.” Padilla likens the experience to a switch going off in his brain that unleashed the power of the universe, the light of the creator, the energy that ties together all living things. “It traveled through my body, into my bloodstream,” he recalls. “It was just incredible.”

It was also Padillas twenty-first birthday. He had to get back down the mountain because hed planned a big party for all his pill-popping friends. But when he walked into the door of his Anaheim apartment that evening, nothing looked familiar to him. “It was like whoever lived there wasnt me,” he says. “I had no idea who that person was.” He looked around his apartment in disgust. On the wall hung a velvet painting with a cartoonish depiction of the Devil amid a cornucopia of hypodermic needles and champagne glasses.

A stack of pornography lay next to his bed; on the coffee table sat a big salad bowl full of speed& party treats for Padilla's birthday celebration.Padilla grabbed the salad bowl and walked to his bathroom. “I dumped all the bennies, and yellows and reds in the toilet,” he says. “I kept the pot—nothing wrong with pot.” He went back to his living room, sat down on the couch, and thought about what he had just done. “I'm sitting there, just thinking, ‘Where do I go now?”

Before he could answer his own question, guests began to arrive. Padilla felt like a stranger in his own house. “‘Everybody has to leave,” he announced. “I shut down the party.” The next day, Padilla and Harrington drove around all day in Harringtons Porsche, selling pot. When Padilla got home, he sat down on his deck and started cleaning his oven grill, wondering how his life had gotten so out of control that he was sleeping with five different women. “Im fucking scum,” he told himself. “I ain't doing this shit anymore.”As he sat there scrubbing away his acid hangover, a man walked around the corner of Padillas apartment building and introduced himself.

The stranger was wearing a black leather jacket and looked like a Chicago hit man. He had a pockmarked face, stood over six feet tall, and must have weighed at least 275 pounds. “Hey, are you Eddie?” he asked. “Some friends of yours told me I could buy some weed from you.” Immediately, Padilla knew the man was trouble—either an informant or an undercover cop. “Sure,” he answered. “But I ran out. I have some coming in later this afternoon. Come back around seven P.M. and buy whatever you want.”

When the man left, Padilla telephoned Harrington and told him the cops had just been to his house and he needed to get out of town.Padillas timing couldnt have been better. Harrington told him that he and Griggs and the rest of their friends were moving out of Anaheim. Griggs had suffered a fire at his house—incense candles that had tipped over and needed a new place to live.

Anaheim was getting too hot, as Padilla's own experience with the presumed narc seemed to indicate. The next morning, Padilla and Harrington moved into a cabin in Silverado Canyon, a wooded retreat northeast of town. John and Carol Griggs relocated to a large stone building in nearby Modjeska Canyon. “We were all out in the country now,” Padilla concludes. “It was a perfect hideout.”

ORANGE SUNSHINE. Copyright & copy; 2010 by Nicholas Schou.

All rights reserved. For information, address

St. Martins Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

The Farmer

N THE MID-1950s, Anaheim, California, a smog-choked working-class town fifteen miles from the nearest beach, was bursting with recent Mexican immigrants and a mass migration of blue-collar white Americans who had fled south from the wave of black families who began to move into Los Angeles suburbs like Watts and Compton after the Second World War.

A century after it was founded by German immigrants as a farming community in 1857, Anaheim's boundless orange groves were quickly being devoured by factories and suburban tract. In 1955, the city's most famous feature, the Disneyland Theme Park, opened its doors and, at about that time -- the exact date is unclear a tough young Okie with an awkward stutter arrived with his family to find the American dream.

Long before he became Timothy Leary's self-described spiritual guru and the leader of the secretive group of drug smugglers who literally provided the fuel for Americas psychedelic revolution, back when John Griggs was still in junior high school, his classmates knew him as an occasionally mean-spirited badass prone to picking fights. He was short but wiry and muscular a champion wrestler, to boot- and wore his dark, fine hair slicked back from his forehead in a jaunty pompadour. His piecing blue eyes seemed to be pulled downward by some force beyond gravity, giving his face a somber, almost tragic expression, even when accompanied by his perpetually crooked and mischievous-seeming shit-eating grin.

John Griggss Graduation Photo, Anaheim High School, 1961.

When Griggs spoke, he tended to stutter for the first few syllables, a speech impediment that might have been amplified by the amphetamine pills he was known to pop like candy as a teenager. He spoke fast, and the stutter would disappear a few words into each sentence. He had a quick wit and an uncanny ability to size people up. Few people who knew him ever saw Griggs actually fight. He didn't have to use his fists. Instead, Griggs would walk up to a guy he didnt like, usually someone much more muscular or who had a reputation as a bully, and start hurling insults and threats at his rival. If the guy didn't back off, Griggss buddies would suddenly appear out of nowhere, jump in, and start kicking the shit out of the offending party.

Robert Ackerly, a tall, lanky kid with stringy dark hair and an impudent smirk that never left his face, befriended Griggs at Anaheim High School. Ackerly hung out with a trio of brothers, Tommy, JC, and Freddy Tunnell, whose parents were friends with the Griggs family in Oklahoma and who had moved west together. Ackerly was a few years younger than Griggs but best friends with Tommy Tunnell, who, like his brothers, and Griggs, for that matter, was a rebellious, unruly jock.

Tunnell introduced Ackerly to Griggs at a party in 1958. Griggs and the rest of the wrestling team, decked out in blue nylon jackets with varsity letters, were drunk and angry. Griggs boasted loudly to Ackerly that they planned to crash another party and beat the shit out of the captain of a wrestling team from a rival high school. Griggs called his coterie of fellow wrestlers the Blue Jackets.

In Ackerly's telling, the gang represents the earliest incarnation of Griggss organizing abilities that would ultimately create the legendary Brotherhood of Eternal Love.

Griggs was already dating an attractive young brunette from Long Beach, Carol Horan, whom he would marry in 1961, the year he graduated from high school, a few classes behind Bobby Hatfield, half of the legendary “blue-eyed soul” duo the Righteous Brothers, whose early-1960s hits included “Unchained Melody” and “You've Lost That Loving Feeling.”

By then, Griggs had left the Blue Jackets behind and taken over the Street Sweepers, an infamous Anaheim car club; its members, who met at a Mexican grease joint called the Bean Hut, bounced back and forth between school and juvenile hall, staging impromptu drag races and cruising around in German army helmets, drunk or high on speed or pot, throwing water balloons and eggs at anyone they didnt know or didn't like.

Ackerly was something of a badass himself, but not nearly so much as his older brother Dick, a barroom brawler so notorious that fighters from as far away as Boston and Chicago would come to town specifically hoping to break his nose. Dick taught Ackerly how to box. His first fight took place just three days after he moved to Anaheim from Los Angeles in 1956, when he was just twelve years old, a freshman at Fremont Junior High School. Someone who didn't like the way Ackerly was looking at his girlfriend grabbed him by the neck and started kicking him in the nuts until his brother Dick ended the brawl by punching his attacker in the head.