The History Channel Is Finally Telling

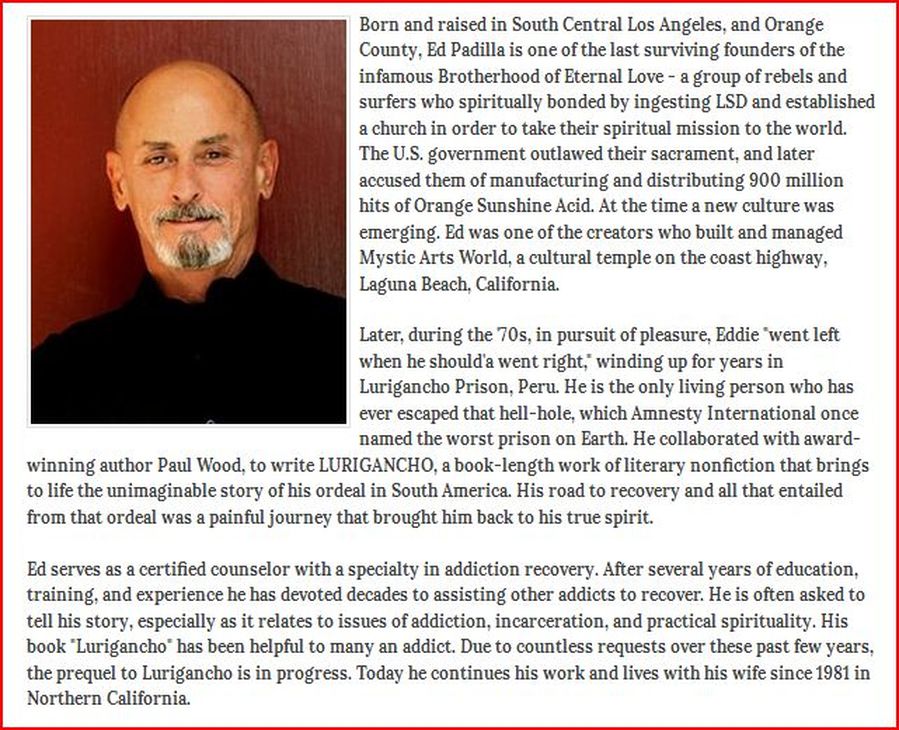

the Stunning Secret Story of the War on Drugs

Jon Schwarz

June 18 2017

https://theintercept.com/2017/06/18/the-history-channel-is-finally-telling-the-stunning-secret-story-of-the-war-on-drugs/

Sunday night and running through Wednesday the History Channel is showing a new four-part series called “America’s War on Drugs.” Not only is it an important contribution to recent American history, it’s also the first time U.S. television has ever told the core truth about one of the most important issues of the past 50 years.That core truth is: The war on drugs has always been a pointless sham.

For decades the federal government has engaged in a shifting series of alliances of convenience with some of the world’s largest drug cartels. So while the U.S. incarceration rate has quintupled since President Richard Nixon first declared the war on drugs in 1971, top narcotics dealers have simultaneously enjoyed protection at the highest levels of power in America.

On the one hand, this shouldn’t be surprising. The voluminous documentation of this fact in dozens of books has long been available to anyone with curiosity and a library card.

Yet somehow, despite the fact the U.S. has no formal system of censorship, this monumental scandal has never before been presented in a comprehensive way in the medium where most Americans get their information: TV.

That’s why “America’s War on Drugs” is a genuine milestone. We’ve recently seen how ideas that once seemed absolutely preposterous and taboo — for instance, that the Catholic Church was consciously safeguarding priests who sexually abused children, or that Bill Cosby may not have been the best choice for America’s Dad — can after years of silence finally break through into popular consciousness and exact real consequences. The series could be a watershed in doing the same for the reality behind one of the most cynical and cruel policies in U.S. history.

The series, executive produced by Julian P. Hobbs, Elli Hakami, and Anthony Lappé, is a standard TV documentary; there’s the amalgam of interviews, file footage, and dramatic recreations. What’s not standard is the story told on camera by former Drug Enforcement Administration operatives as well as journalists and drug dealers themselves. (One of the reporters is Ryan Grim, The Intercept’s Washington bureau chief and author of “This Is Your Country on Drugs: The Secret History of Getting High in America.”)

There’s no mealy mouthed truckling about what happened. The first episode opens with the voice of Lindsay Moran, a one-time clandestine CIA officer, declaring, “The agency was elbow deep with drug traffickers.”

Then Richard Stratton, a marijuana smuggler turned writer and television producer, explains, “Most Americans would be utterly shocked if they knew the depth of involvement that the Central Intelligence Agency has had in the international drug trade.”

Next, New York University professor Christian Parenti tells viewers, “The CIA is from its very beginning collaborating with mafiosas who are involved in the drug trade because these mafiosas will serve the larger agenda of fighting communism.”

For the next eight hours, the series sprints through history that’s largely the greatest hits of the U.S. government’s partnership with heroin, hallucinogen, and cocaine dealers. That these greatest hits can fill up most of four two-hour episodes demonstrates how extraordinarily deep and ugly the story is.

First we learn about the CIA working with Florida mob boss Santo Trafficante Jr. in the early 1960s. The CIA wanted Fidel Castro dead and, in return for Trafficante’s help in various assassination plots, was willing to turn a blind eye to the extensive drug trafficking by Trafficante and his allied Cuban exiles.

Then there’s the extremely odd tale of how the CIA imported significant amounts of LSD from its Swiss manufacturer in hopes that it could be used for successful mind control. Instead, by dosing thousands of young volunteers including Ken Kesey, Whitey Bulger, and Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter, the agency accidentally helped popularize acid and generate the 1960s counterculture of psychedelia.

During the Vietnam War, the U.S. allied with anti-communist forces in Laos that leveraged our support to become some of the largest suppliers of opium on earth. Air America, a CIA front, flew supplies for the guerrillas into Laos and then flew drugs out, all with the knowledge and protection of U.S. operatives.

The same dynamic developed in the 1980s as the Reagan administration tried to overthrow the Sandinista government in Nicaragua. The planes that secretly brought arms to the contras turned around and brought cocaine back to America, again shielded from U.S. law enforcement by the CIA.

Most recently, there’s our 16-year-long war in Afghanistan. While less has been uncovered about the CIA’s machinations here, it’s hard not to notice that we installed Hamid Karzai as president while his brother apparently was on the CIA payroll and, simultaneously, one of the country’s biggest opium dealers. Afghanistan now supplies about 90 percent of the world’s heroin.

To its credit, the series makes clear that this is not part of a secret government plot to turn Americans into drug addicts.

But, as Moran puts it, “When the CIA is focused on a mission, on a particular end, they’re not going to sit down and pontificate about ‘What are the long-term, global consequences of our actions going to be?’” Winning their secret wars will always be their top priority, and if that requires cooperation with drug cartels that are flooding the U.S. with their product, so be it. “A lot of these patterns that have their origins in the 1960s become cyclical,” Moran adds. “Those relationships develop again and again throughout the war on drugs.”

What makes this history so grotesque is the government’s mind-breaking levels of hypocrisy. It’s like Donald Trump declaring a War on Real Estate Developers that fills prisons with people who occasionally rent out their spare bedroom on Airbnb.

That brings us back to Charles Grassley. Grassley is now chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, a longtime committed drug warrior and — during the 1980s — a supporter of the contras.

Yet even Grassley is showing signs that he realizes there may have been some flaws in the war on drugs since the beginning. He recently has co-sponsored a bill that would reduce minimum sentences for drug offenses.

So now that the History Channel has granted Grassley his wish and is broadcasting this extraordinarily important history, it’s our job to make sure he and everyone like him sits down and watches it. That this series exists at all shows that we’re at a tipping point with this brazen, catastrophic lie. We have to push hard enough to knock it over.

the Stunning Secret Story of the War on Drugs

Jon Schwarz

June 18 2017

https://theintercept.com/2017/06/18/the-history-channel-is-finally-telling-the-stunning-secret-story-of-the-war-on-drugs/

Sunday night and running through Wednesday the History Channel is showing a new four-part series called “America’s War on Drugs.” Not only is it an important contribution to recent American history, it’s also the first time U.S. television has ever told the core truth about one of the most important issues of the past 50 years.That core truth is: The war on drugs has always been a pointless sham.

For decades the federal government has engaged in a shifting series of alliances of convenience with some of the world’s largest drug cartels. So while the U.S. incarceration rate has quintupled since President Richard Nixon first declared the war on drugs in 1971, top narcotics dealers have simultaneously enjoyed protection at the highest levels of power in America.

On the one hand, this shouldn’t be surprising. The voluminous documentation of this fact in dozens of books has long been available to anyone with curiosity and a library card.

Yet somehow, despite the fact the U.S. has no formal system of censorship, this monumental scandal has never before been presented in a comprehensive way in the medium where most Americans get their information: TV.

That’s why “America’s War on Drugs” is a genuine milestone. We’ve recently seen how ideas that once seemed absolutely preposterous and taboo — for instance, that the Catholic Church was consciously safeguarding priests who sexually abused children, or that Bill Cosby may not have been the best choice for America’s Dad — can after years of silence finally break through into popular consciousness and exact real consequences. The series could be a watershed in doing the same for the reality behind one of the most cynical and cruel policies in U.S. history.

The series, executive produced by Julian P. Hobbs, Elli Hakami, and Anthony Lappé, is a standard TV documentary; there’s the amalgam of interviews, file footage, and dramatic recreations. What’s not standard is the story told on camera by former Drug Enforcement Administration operatives as well as journalists and drug dealers themselves. (One of the reporters is Ryan Grim, The Intercept’s Washington bureau chief and author of “This Is Your Country on Drugs: The Secret History of Getting High in America.”)

There’s no mealy mouthed truckling about what happened. The first episode opens with the voice of Lindsay Moran, a one-time clandestine CIA officer, declaring, “The agency was elbow deep with drug traffickers.”

Then Richard Stratton, a marijuana smuggler turned writer and television producer, explains, “Most Americans would be utterly shocked if they knew the depth of involvement that the Central Intelligence Agency has had in the international drug trade.”

Next, New York University professor Christian Parenti tells viewers, “The CIA is from its very beginning collaborating with mafiosas who are involved in the drug trade because these mafiosas will serve the larger agenda of fighting communism.”

For the next eight hours, the series sprints through history that’s largely the greatest hits of the U.S. government’s partnership with heroin, hallucinogen, and cocaine dealers. That these greatest hits can fill up most of four two-hour episodes demonstrates how extraordinarily deep and ugly the story is.

First we learn about the CIA working with Florida mob boss Santo Trafficante Jr. in the early 1960s. The CIA wanted Fidel Castro dead and, in return for Trafficante’s help in various assassination plots, was willing to turn a blind eye to the extensive drug trafficking by Trafficante and his allied Cuban exiles.

Then there’s the extremely odd tale of how the CIA imported significant amounts of LSD from its Swiss manufacturer in hopes that it could be used for successful mind control. Instead, by dosing thousands of young volunteers including Ken Kesey, Whitey Bulger, and Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter, the agency accidentally helped popularize acid and generate the 1960s counterculture of psychedelia.

During the Vietnam War, the U.S. allied with anti-communist forces in Laos that leveraged our support to become some of the largest suppliers of opium on earth. Air America, a CIA front, flew supplies for the guerrillas into Laos and then flew drugs out, all with the knowledge and protection of U.S. operatives.

The same dynamic developed in the 1980s as the Reagan administration tried to overthrow the Sandinista government in Nicaragua. The planes that secretly brought arms to the contras turned around and brought cocaine back to America, again shielded from U.S. law enforcement by the CIA.

Most recently, there’s our 16-year-long war in Afghanistan. While less has been uncovered about the CIA’s machinations here, it’s hard not to notice that we installed Hamid Karzai as president while his brother apparently was on the CIA payroll and, simultaneously, one of the country’s biggest opium dealers. Afghanistan now supplies about 90 percent of the world’s heroin.

To its credit, the series makes clear that this is not part of a secret government plot to turn Americans into drug addicts.

But, as Moran puts it, “When the CIA is focused on a mission, on a particular end, they’re not going to sit down and pontificate about ‘What are the long-term, global consequences of our actions going to be?’” Winning their secret wars will always be their top priority, and if that requires cooperation with drug cartels that are flooding the U.S. with their product, so be it. “A lot of these patterns that have their origins in the 1960s become cyclical,” Moran adds. “Those relationships develop again and again throughout the war on drugs.”

What makes this history so grotesque is the government’s mind-breaking levels of hypocrisy. It’s like Donald Trump declaring a War on Real Estate Developers that fills prisons with people who occasionally rent out their spare bedroom on Airbnb.

That brings us back to Charles Grassley. Grassley is now chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, a longtime committed drug warrior and — during the 1980s — a supporter of the contras.

Yet even Grassley is showing signs that he realizes there may have been some flaws in the war on drugs since the beginning. He recently has co-sponsored a bill that would reduce minimum sentences for drug offenses.

So now that the History Channel has granted Grassley his wish and is broadcasting this extraordinarily important history, it’s our job to make sure he and everyone like him sits down and watches it. That this series exists at all shows that we’re at a tipping point with this brazen, catastrophic lie. We have to push hard enough to knock it over.

S 1 E 1

HISTORY CHANNEL:

Acid, Spies, & Secret Experiments

tv-14 v,s,l,dThe roots of America’s War on Drugs reveals secret assassination attempts, the CIA’s bizarre experiments with LSD and support of heroin traffickers, LSD parachuting from the sky, and how it led to a five decade war.

Aired on:

Jun 18, 2017

Available Until:

Jul 24, 2017

Duration:

1h 24m 3s

HISTORY CHANNEL:

Acid, Spies, & Secret Experiments

tv-14 v,s,l,dThe roots of America’s War on Drugs reveals secret assassination attempts, the CIA’s bizarre experiments with LSD and support of heroin traffickers, LSD parachuting from the sky, and how it led to a five decade war.

Aired on:

Jun 18, 2017

Available Until:

Jul 24, 2017

Duration:

1h 24m 3s

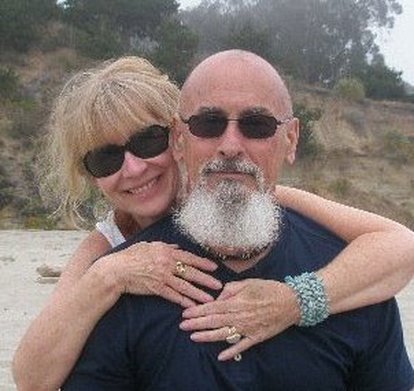

The Brotherhood of Eternal Love is alive and well in the Hearts of All the true Brother's. I stepped off the Spiritual Path for a minute and experienced the "Dark Side" and today I walk my talk and live my life according to what The Brotherhood is All about. Sure as Hell was never about Drugs or the ego building greatest smuggler's or even who made the most acid.

Love, Light, Life. All God All the Time. Om Mani Padme Hum

https://www.amazon.com/Lurigancho-Mr-Edward-Padilla/dp/0970620055

Love, Light, Life. All God All the Time. Om Mani Padme Hum

https://www.amazon.com/Lurigancho-Mr-Edward-Padilla/dp/0970620055

"Pirate of Penance"

Before Johnny Depp's Capt. Jack Sparrow,

Eddie "Spaghetti" Padilla Gave Pirates and Love a Bad Name

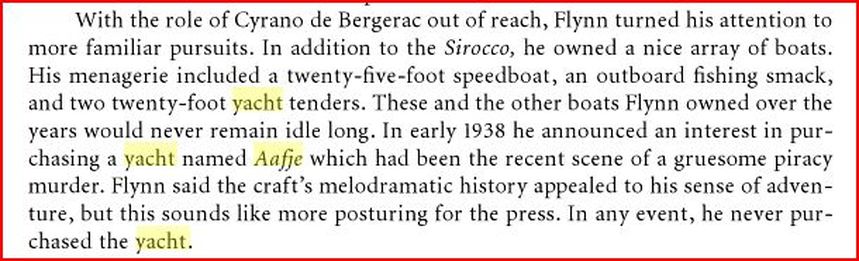

The Aafje met up with Eddie Padilla at Manzanillo in early 1970. It had been sailed from St. Thomas, and it was now crewed by a half dozen other Brotherhood of Eternal Love members – who had never sailed before in their lives. Eddie had been working for the last year or so, with “Papa” – Pedro Aviles Perez. “Papa” was the Sinaloan marijuana supplier of the Brotherhood. It had been Eddie’s dream to purchase a boat, which he planned to use to smuggle hashish from Pakistan back to the States. Eddie referred to himself as a “spiritual warrior” and the purchase of the boat signified, to him, a fulfilling of a dream. That dream, apparently began with loading up the Aafje with over 1500 kilograms of the best Sinaloan marijuana, while it stood anchor just outside the twelve mile limit. Motor launch after motor launch disgorged their loads to the stately old Aafje, and then, with Eddie and all that “Maui Wowie” material now aboard – they set sail for Maui. -- Eddie Padilla

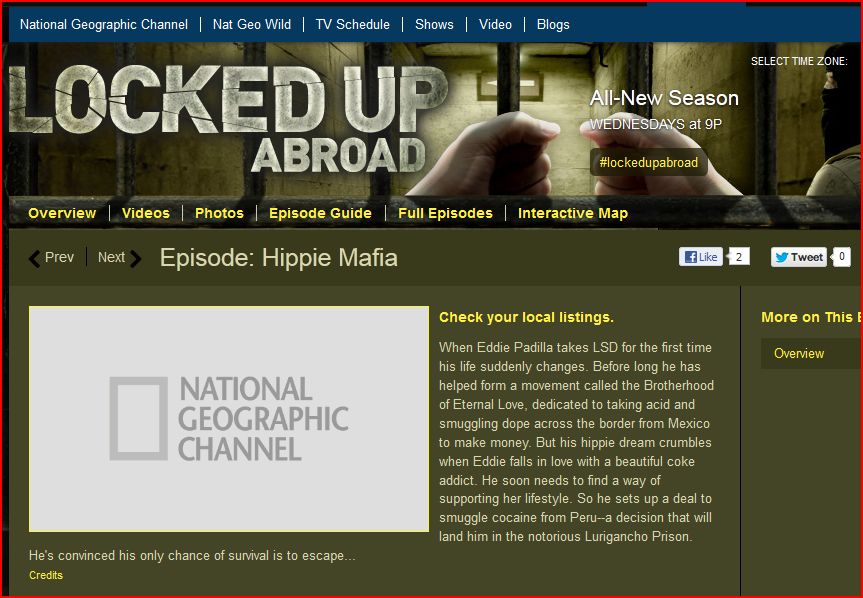

VIDEO: LOCKED UP ABROAD - HIPPIE MAFIA

http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x1t3ps4_locked-up-abroad-hippy-mafia_shortfilms

http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x1t3ps4_locked-up-abroad-hippy-mafia_shortfilms

|

"Edward Padilla's gritty street prose takes the reader into a desperate Heart of Darkness from which not many could ever emerge. But this gripping narrative turns emergence into a transcendent awakening and genuine rebirth. This is the real stuff, no modifiers required."

John Kent Harrison screenwriter/director "Eddie Padilla embodies so much of the promise and peril of post-War Southern California that it makes your head spin: a multiracial child of the New West; schooled by surfers, street fighters, and smugglers; turned on as a '60s seeker; turned out as a '70s nihilist. In Lurigancho Prison, Peru, a Dante-esque catalog of horrors, Padilla paid for California's broken dreams as much as his own. His brave escape and ongoing recovery offer a dagger of redemption and hope in the fight against 21st century cynicism and apathy." Joe Donnelly co-editor/founder Slake: Los Angeles, author of "The Pirate of Penance" |

https://www.createspace.com/4245678

by Mr. Edward Padilla with Mr. Paul Wood BUY: http://www.amazon.com/Lurigancho-Mr-Edward-Padilla/dp/0970620055 A sensational-and true-prison escape story in the tradition of Papillon and Midnight Express. Edward Padilla, an American, is the only living person ever to escape from the world's foulest prison-Lurigancho Prison in Peru. Here is the true story of his four-year ordeal and his miraculous flight to freedom. A founding member of the now notorious "hippie" church called The Brotherhood of Eternal Love, Ed is one of the few surviving core members of that group, the only one to come forward with brutal honesty in the telling of this story. "A wonderfully gritty story of transcendence of the physical and the spiritual. Serve time with Ed and discover hell and heaven. Unique and extraordinary." Jeremy Tarcher publisher, Tarcher Books and Seven Years in Tibet "A harrowing account of one of the most infamous hell-holes on earth, and a thrilling tale of betrayed ideals, adventure, escape and redemption." Nicholas Schou author of Kill the Messenger, Orange Sunshine, and The Weed Runners (forthcoming) "An astonishing true story that has every twist and turn you could imagine. Eddie's is a story that plunges to the bleakest depths and soars to the greatest heights. Guns, drugs, girls, South American hell-holes-it has it all...." Nick Green director of the National Geographic documentary "The Hippie Mafia" Publication Date:May 17 2013ISBN/EAN13:0970620055 / 9780970620057Page Count:410Binding Type:US Trade PaperTrim Size:5.5" x 8.5"Language:EnglishColor:Black and WhiteRelated Categories:Biography & Autobiography / Personal Memoirs |

Eddie Padilla's Escape From Lurigancho

The onetime OC man is the only man still alive who escaped from Peru's most notorious prison

By Nick Schou Thursday, Jun 20 2013

http://www.ocweekly.com/2013-06-20/news/eddie-padilla-lurigancho-peru-brotherhood-of-eternal-love/

When Eddie Padilla first learned he was headed to Peru's San Juan de Lurigancho Prison, he was happy.

It was the winter of 1975, and he had just spent the past few weeks locked up in a closet in an ex-drug dealer's mansion in Peru's capital, Lima, a building that Peruvian Internal Police had seized and converted into a detention center and torture chamber. But the corrupt cops who had busted him and his friends for a cocaine-smuggling venture gone awry had a plan. In return for a large chunk of change, they'd fabricate a story that would clear the trio of the crime. All Padilla and his pals had to do was wait six months in Lurigancho. It would be easy, the cops said, a vacation. It wasn't so much a prison as a country club, with tennis courts and a swimming pool. . .

The onetime OC man is the only man still alive who escaped from Peru's most notorious prison

By Nick Schou Thursday, Jun 20 2013

http://www.ocweekly.com/2013-06-20/news/eddie-padilla-lurigancho-peru-brotherhood-of-eternal-love/

When Eddie Padilla first learned he was headed to Peru's San Juan de Lurigancho Prison, he was happy.

It was the winter of 1975, and he had just spent the past few weeks locked up in a closet in an ex-drug dealer's mansion in Peru's capital, Lima, a building that Peruvian Internal Police had seized and converted into a detention center and torture chamber. But the corrupt cops who had busted him and his friends for a cocaine-smuggling venture gone awry had a plan. In return for a large chunk of change, they'd fabricate a story that would clear the trio of the crime. All Padilla and his pals had to do was wait six months in Lurigancho. It would be easy, the cops said, a vacation. It wasn't so much a prison as a country club, with tennis courts and a swimming pool. . .

May 22, 2013; Don't miss Eddie Padilla's untold story on

Locked Up Abroad & His New BOOK on Amazon

http://channel.nationalgeographic.com/channel/locked-up-abroad/episodes/hippie-mafia/

Locked Up Abroad & His New BOOK on Amazon

http://channel.nationalgeographic.com/channel/locked-up-abroad/episodes/hippie-mafia/

https://www.facebook.com/orangesunshinemovie/timeline

by Joe Donnelly

“John was never anyone I would follow,” insists Edward Padilla, who also befriended Griggs in high school. “He was a sneaky, manipulative little bastard. He would usually pick a fight with someone bigger, and when the fight started, everyone would start coming out of the woodwork.” Padilla’s family moved to Orange County in the early 1950s from South Central Los Angeles. Although his mother was of German-Irish extraction, Padilla’s dad, a construction contractor, was half black and half Native American and commuted back to Los Angeles for work, because, as a nonwhite, he couldn’t get a single job in Orange County. “I had dark skin,” Padilla says. “Because I wasn’t Mexican or white, I wasn’t enough of any one color to be part of either crowd.”

When he turned sixteen, Padilla, like everyone else he knew, went to Disneyland to apply for a summer job. “I was the only one not to get hired,” he says. “Anaheim was a different world back then.”In school, Padilla established himself as the class troublemaker. One day his teacher told him to shut up and sit down. Padilla ignored him, so the teacher grabbed him by the throat and slammed him into his seat. Padilla kicked the teacher in the balls. The teacher went home for the day to nurse his wounds and Padilla ended up being expelled from Anaheim’s public education system.

He attended St. Boniface Parish School, a privately run Catholic institution, where he scraped with an older student who made the mistake of insulting Padilla’s mother. “What are you looking at?” the kid asked. “Fuck you,” Padilla answered. “I’ll fuck your mother,” the kid responded. Padilla punched him in the face until the kid was lying on the floor unconscious. “I broke his head open, so they sent me to juvenile hall.

”After he got out, Padilla attended Servite High School, an all-boys facility full of public school rejects taught by robe-wearing priests. “We were some rough guys,” recalls Padilla, who by now had bulked up into a muscular athlete. During his sophomore year, Padilla insulted one of his teachers, a former professional football player who promptly slapped him across the face. “You slap like a girl,” Padilla observed. The teacher slapped him again, hard enough to send Padilla reeling from his seat. He picked up his desk and swung it at the teacher.

That stunt sent Padilla to another private school in Downey, where he joined the football team and resumed fighting. When he attacked a fellow football player who wound up in the hospital with cracked cheekbones and his jaw wired together, Padilla found himself again expelled and sent back to Anaheim.At a sock hop during his first year back at Anaheim High School, Padilla danced with a girl who happened to be dating a friend of Griggs’s named Mike Bias.

The dance ended and Bias and about ten other angry-looking guys including John Griggs walked up to Padilla. “You fucked up,” Griggs announced. “You don’t mess with our girls. We’re going to kick your ass.” Padilla continued dancing with the girl. When the sock hop ended, he went outside, fists clenched, ready to rumble. Nobody was there. “I was glad,” he says. “Don’t get me wrong. Ten to one didn’t sound fun.” The next day, however, Griggs approached Padilla with an olive branch, telling him that the rest of his gang was planning to ambush him.

A few weeks later, Griggs told Padilla the fight would happen that evening in an orange grove outside of town. He drove Padilla to the location and pumped him with information about who was going to try to take him down. He warned Padilla to watch out for a sucker puncher named Franco who planned to wait until Padilla had been worn down fighting other contenders before he stepped in to finish him off.“I rode out to this grassy meadow in the middle of this orange grove in John’s 1938 Cadillac,” Padilla recalls. “There were probably fifty kids there, mostly guys, standing in a circle.”

Padilla cracked his knuckles and readied himself. Without warning, a couple of football players rushed him simultaneously. One of them charged into Padilla, sending him flying backward. He leaned over and sank his teeth into the guy’s back. As Padilla pushed him away, the next jock came flying forward. Suddenly, one of Griggs’s friends, who unbeknownst to Padilla had been appointed by Griggs to intervene, stepped forward to protect him. “Little by little, even though we had different agendas, I realized I was covered in a strange way,” Padilla says. “Johnny was always trying to have a gang of guys and that was the opposite of me. I was a loner, but John needed a lot of people to accomplish what he wanted. He was a masterful politician. He had a gift of gab, and people followed John.

”Padilla and Griggs were both fans of The Untouchables, a television show broadcast on ABC every Thursday night from 1959 to 1963. Based on the memoir by legendary G-man Eliot Ness, the show fictionalized his pursuit of the notorious Chicago mob boss Al Capone. To Padilla, it seemed to provide free lessons in how to operate a successful criminal enterprise. “Capone and his gang were so successful because they didn’t use violence to achieve their aims,” he says. “I watched that show religiously, every Thursday night,” Padilla says. “I wanted to be a successful criminal. My product was going to be pot and pills and I was going to run all of Orange County.” Inspired by the show’s character Arnold “Spatz” Vincent, Padilla went to a thrift store and bought a pair of spats and black and white wing-tipped shoes, slacks, a button-down vest, and a Gant shirt with a button-down collar.

Griggs and his crew were dressing up like their favorite gangsters as well. Griggs thought of himself as Capone, and his 1938 Cadillac testified to his admiration for the mob boss.Eddie Padilla’s dream of becoming Orange County’s biggest pot dealer was deferred by several jail stints, everything from indecent exposure to dealing drugs to assaulting a cop with a wrist pin, a steel bar that when gripped in a tight fist could land a deadly punch. His lawyer persuaded a judge to send him to Atascadero, a hospital for the criminally insane, where Padilla spent the next eighteen months. By now, he was eighteen years old and had knife scars up and down his arms and was missing several front teeth.

Padilla’s stint in the loony bin convinced him to leave street fighting behind him. He married his high school sweetheart and rented an apartment with the money he was making selling pot, cheap weed smuggled across the border from Mexico. In those days, marijuana was divided into “lids” which referred to a whole can of Prince Albert brand rolling tobacco, and “fingers,” which was a finger’s width of pot inside the can.Soon, Padilla wasn’t just dealing, he was supplying pot to other dealers, like Jack “Dark Cloud” Harrington, a street fighter from Westminster.

One night, Padilla went over to Harrington’s house to see if he needed any more pot to sell. Sitting in the living room was his old friend John Griggs, whom Padilla hadn’t seen since high school. Griggs was now married, working in the nearby oil fields of Yorba Linda and, like Padilla, dealing a lot of pot.“I became the biggest dealer in Anaheim, and maybe Garden Grove,” Padilla says. “I had a lot of customers and went around meticulously turning people on to pot. I believed in pot.”

One day, Padilla’s pot supplier introduced him to someone who was bringing kilograms of weed across the border every weekend. Now Padilla could sell half pounds and quarter pounds of marijuana at a pop. He went back to all the people he knew, turning them on to pot and looking for the next adventure. “I was twenty years old and figured I needed to go down to Mexico and do something worthy,” he says. “Being an adrenaline junkie, smuggling was appealing to me. I couldn’t wait.”

http://us.macmillan.com/BookCustomPage_New.aspx?isbn=9780312607173&isprint=true

“John was never anyone I would follow,” insists Edward Padilla, who also befriended Griggs in high school. “He was a sneaky, manipulative little bastard. He would usually pick a fight with someone bigger, and when the fight started, everyone would start coming out of the woodwork.” Padilla’s family moved to Orange County in the early 1950s from South Central Los Angeles. Although his mother was of German-Irish extraction, Padilla’s dad, a construction contractor, was half black and half Native American and commuted back to Los Angeles for work, because, as a nonwhite, he couldn’t get a single job in Orange County. “I had dark skin,” Padilla says. “Because I wasn’t Mexican or white, I wasn’t enough of any one color to be part of either crowd.”

When he turned sixteen, Padilla, like everyone else he knew, went to Disneyland to apply for a summer job. “I was the only one not to get hired,” he says. “Anaheim was a different world back then.”In school, Padilla established himself as the class troublemaker. One day his teacher told him to shut up and sit down. Padilla ignored him, so the teacher grabbed him by the throat and slammed him into his seat. Padilla kicked the teacher in the balls. The teacher went home for the day to nurse his wounds and Padilla ended up being expelled from Anaheim’s public education system.

He attended St. Boniface Parish School, a privately run Catholic institution, where he scraped with an older student who made the mistake of insulting Padilla’s mother. “What are you looking at?” the kid asked. “Fuck you,” Padilla answered. “I’ll fuck your mother,” the kid responded. Padilla punched him in the face until the kid was lying on the floor unconscious. “I broke his head open, so they sent me to juvenile hall.

”After he got out, Padilla attended Servite High School, an all-boys facility full of public school rejects taught by robe-wearing priests. “We were some rough guys,” recalls Padilla, who by now had bulked up into a muscular athlete. During his sophomore year, Padilla insulted one of his teachers, a former professional football player who promptly slapped him across the face. “You slap like a girl,” Padilla observed. The teacher slapped him again, hard enough to send Padilla reeling from his seat. He picked up his desk and swung it at the teacher.

That stunt sent Padilla to another private school in Downey, where he joined the football team and resumed fighting. When he attacked a fellow football player who wound up in the hospital with cracked cheekbones and his jaw wired together, Padilla found himself again expelled and sent back to Anaheim.At a sock hop during his first year back at Anaheim High School, Padilla danced with a girl who happened to be dating a friend of Griggs’s named Mike Bias.

The dance ended and Bias and about ten other angry-looking guys including John Griggs walked up to Padilla. “You fucked up,” Griggs announced. “You don’t mess with our girls. We’re going to kick your ass.” Padilla continued dancing with the girl. When the sock hop ended, he went outside, fists clenched, ready to rumble. Nobody was there. “I was glad,” he says. “Don’t get me wrong. Ten to one didn’t sound fun.” The next day, however, Griggs approached Padilla with an olive branch, telling him that the rest of his gang was planning to ambush him.

A few weeks later, Griggs told Padilla the fight would happen that evening in an orange grove outside of town. He drove Padilla to the location and pumped him with information about who was going to try to take him down. He warned Padilla to watch out for a sucker puncher named Franco who planned to wait until Padilla had been worn down fighting other contenders before he stepped in to finish him off.“I rode out to this grassy meadow in the middle of this orange grove in John’s 1938 Cadillac,” Padilla recalls. “There were probably fifty kids there, mostly guys, standing in a circle.”

Padilla cracked his knuckles and readied himself. Without warning, a couple of football players rushed him simultaneously. One of them charged into Padilla, sending him flying backward. He leaned over and sank his teeth into the guy’s back. As Padilla pushed him away, the next jock came flying forward. Suddenly, one of Griggs’s friends, who unbeknownst to Padilla had been appointed by Griggs to intervene, stepped forward to protect him. “Little by little, even though we had different agendas, I realized I was covered in a strange way,” Padilla says. “Johnny was always trying to have a gang of guys and that was the opposite of me. I was a loner, but John needed a lot of people to accomplish what he wanted. He was a masterful politician. He had a gift of gab, and people followed John.

”Padilla and Griggs were both fans of The Untouchables, a television show broadcast on ABC every Thursday night from 1959 to 1963. Based on the memoir by legendary G-man Eliot Ness, the show fictionalized his pursuit of the notorious Chicago mob boss Al Capone. To Padilla, it seemed to provide free lessons in how to operate a successful criminal enterprise. “Capone and his gang were so successful because they didn’t use violence to achieve their aims,” he says. “I watched that show religiously, every Thursday night,” Padilla says. “I wanted to be a successful criminal. My product was going to be pot and pills and I was going to run all of Orange County.” Inspired by the show’s character Arnold “Spatz” Vincent, Padilla went to a thrift store and bought a pair of spats and black and white wing-tipped shoes, slacks, a button-down vest, and a Gant shirt with a button-down collar.

Griggs and his crew were dressing up like their favorite gangsters as well. Griggs thought of himself as Capone, and his 1938 Cadillac testified to his admiration for the mob boss.Eddie Padilla’s dream of becoming Orange County’s biggest pot dealer was deferred by several jail stints, everything from indecent exposure to dealing drugs to assaulting a cop with a wrist pin, a steel bar that when gripped in a tight fist could land a deadly punch. His lawyer persuaded a judge to send him to Atascadero, a hospital for the criminally insane, where Padilla spent the next eighteen months. By now, he was eighteen years old and had knife scars up and down his arms and was missing several front teeth.

Padilla’s stint in the loony bin convinced him to leave street fighting behind him. He married his high school sweetheart and rented an apartment with the money he was making selling pot, cheap weed smuggled across the border from Mexico. In those days, marijuana was divided into “lids” which referred to a whole can of Prince Albert brand rolling tobacco, and “fingers,” which was a finger’s width of pot inside the can.Soon, Padilla wasn’t just dealing, he was supplying pot to other dealers, like Jack “Dark Cloud” Harrington, a street fighter from Westminster.

One night, Padilla went over to Harrington’s house to see if he needed any more pot to sell. Sitting in the living room was his old friend John Griggs, whom Padilla hadn’t seen since high school. Griggs was now married, working in the nearby oil fields of Yorba Linda and, like Padilla, dealing a lot of pot.“I became the biggest dealer in Anaheim, and maybe Garden Grove,” Padilla says. “I had a lot of customers and went around meticulously turning people on to pot. I believed in pot.”

One day, Padilla’s pot supplier introduced him to someone who was bringing kilograms of weed across the border every weekend. Now Padilla could sell half pounds and quarter pounds of marijuana at a pop. He went back to all the people he knew, turning them on to pot and looking for the next adventure. “I was twenty years old and figured I needed to go down to Mexico and do something worthy,” he says. “Being an adrenaline junkie, smuggling was appealing to me. I couldn’t wait.”

http://us.macmillan.com/BookCustomPage_New.aspx?isbn=9780312607173&isprint=true

Mystic Beginnings

When Lorey Smith was 12 years old, her father loaded her and her brother into his black 1965 Mustang and drove them down the Pacific Coast Highway to this cool little shop called Mystic Arts World. The store sold arts and crafts, organic food and clothing, books about Eastern philosophy, and other things, too. Lorey’s father knew some of the guys who ran Mystic Arts and he thought the outing would be a nice diversion for the kids. It was a short drive from Huntington Beach but an exotic destination, at least for the girl in the back seat.

The year was 1969, and Laguna Beach, once the sleepy refuge of surfers, artists, and bohemians of little consequence, was a center of counterculture foment after a band of outlaws and outcasts went up a mountain with LSD and came down as messengers of love, peace and the transformational qualities of acid and hash. They called themselves the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, and Mystic Arts World was their public face, a hippie hangout where vegetarianism, Buddhism, meditation and all sorts of Aquarian ideals spread like gospel.

Lorey says she felt like Alice in Wonderland when she crossed the threshold and entered Mystic Arts. “It was like walking into a different world,” she tells me 40 years later. “Everything from what was on the walls to the way people were dressed gave off this feeling of love, and, like, freedom.”

Her father bought the kids some beads to keep them busy and Lorey fashioned a necklace. She walked up to a big, handsome guy with long hair and handed it to him.

“He opened up his hands, took the beads and had this big, beaming smile,” she recalls, “and I just felt like, love, and I thought, Someday I want to marry someone like that.”

Into the Gran Azul

Security guards armed with machine guns patrol the grounds of the Gran Azul resort in Lima, Peru. It’s the kind of place you have to know someone to even get close. But on an early winter day in 1975, Eddie Padilla, one of the founders of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, has no trouble booking a room. He is a familiar face on a familiar errand.

Checking in with Padilla are Richard Brewer, a Brother from way back, and their friend James Thomason. “I chose Richard because he’s a good guy,” Padilla remembers. “He’ll get your back. He’s not going to run away. That played out in a way that I never, ever expected.” Thomason is along for the ride—to party and taste some first-class Peruvian flake.

As the manager walks the men to their bungalow, he delivers a strange message. “Your friend is here,” he says.

“Friend?” Padilla asks. “What friend?”

As soon as the manager says the name Fastie, Padilla curses. He’s known the guy since high school where Fastie earned his nickname because he always knew the shortest distance to a quick buck. As far as Padilla is concerned, Fastie is a flashy, loud-mouthed whoremonger—the worst kind of smuggler. Padilla told him not to come to Lima while he was there. To make matters worse, Fastie’s girlfriend is with him, and she has a crush on Padilla. When they run into her, she complains that Fastie has been taking off and leaving her at the hotel.

“She knows he’s been going to see whores and coking out,” Padilla says. “We’re like, Oh, god.” Prostitutes and police are thick as thieves in places like Lima, Peru.

Still, there’s no reason to be paranoid. “All I have to do is spend the night, pick up the coke, give it to a few people, and peel out in 24 hours,” Padilla remembers thinking. Everything was set up ahead of time; the deal should be an in-and-out affair.

Though they had agreed to keep a low profile, Padilla, Brewer, and Thomason decide to go to the compound’s bar that night. It’s an upscale place and they get all dressed up. Fastie is there. Things are tense and Padilla knows better than to dance with Fastie’s girlfriend. But when she asks, something won’t let him say no. Maybe he just wants to rub Fastie’s face in it. Maybe he’s the guy who has to let everyone know he can have the girl. Whatever it is, when they get off the floor, Fastie isn’t amused.

“All of a sudden, in a jealous rage, he gets up, scrapes everyone’s drinks off the bar, and throws a drink on [his girlfriend],” Padilla says. “The bouncer, some Jamaican dude, kicks him out.”

Fastie returns to his room and tosses his girlfriend’s belongings out the window. She ends up spending the night in Padilla’s bungalow.

The next morning, the girlfriend leaves to retrieve her belongings. She never comes back. Fastie isn’t anywhere to be seen either.

If they’d been reading the signs, they might have waited until things settled down to pick up the coke. Instead, Padilla and Brewer stay on schedule and head to a nearby safe house for their load—25 kilos of cocaine worth nearly $200,000—and return to the bungalow without a hitch. Things seem to be back on track.

“It’s so fresh, it’s still damp,” Padilla says. “So I’ve got it on these big, silver serving trays, sitting on a table. James is making a paper of coke [think to-go cup]. Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks is playing. Richard’s doing something … I don’t know what. And I’m writing down numbers. All of the sudden, the door opens. I look and all I see is a chrome-plated .32. Oh, shit. I just thought, wow, my life just ended.”

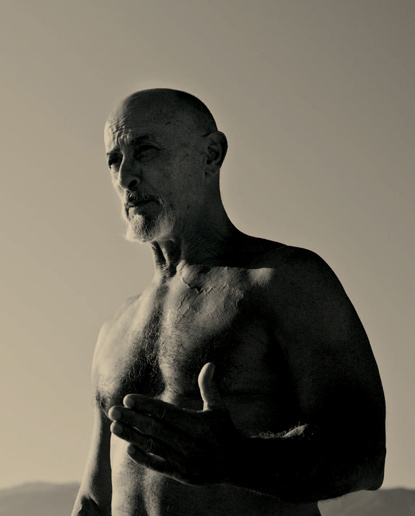

The Making of Eddie Padilla

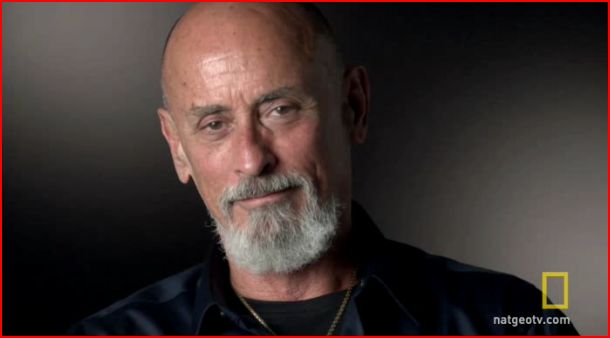

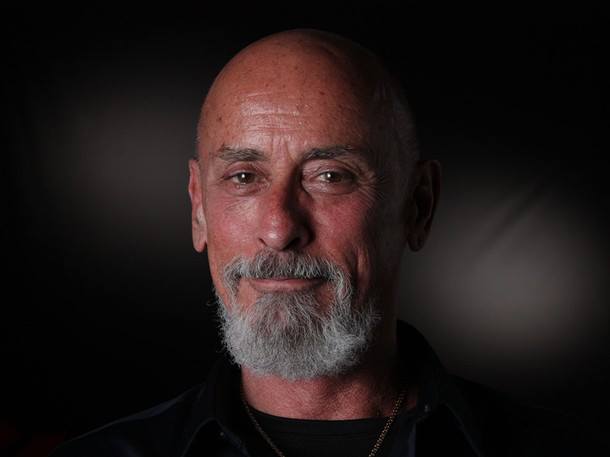

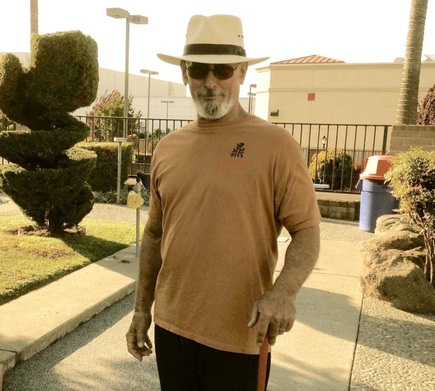

Thirty-four years later, Eddie Padilla emerges from Burbank’s Bob Hope Airport into a balmy Los Angeles autumn night. He has a well-groomed goatee, a shiny, bald dome, and a nose that clearly hasn’t dodged every punch. Wearing a black jacket and tidy slacks, Padilla is muscular and sturdy at 64. He walks like a slightly wounded panther and offers a knuckle-crushing handshake. “Hey, man, thanks for coming to get me,” he says with a lingering SoCal-hippie-surfer accent.

We grab a coffee. Padilla speaks softly, with an economy that could be taken for either circumspection or shyness. The circumspection would be mutual. I had been approached about Padilla through his literary agents; they’d been unsuccessfully shopping his memoir. Right away, I was skeptical. Padilla’s story was epic, harrowing, and hard to believe. Aggravating my suspicions was the memoir’s aggrandizing tone. Plus, I’m not a fan of hippies and their justifications for what often seems like plain irresponsibility or selfishness. Still, I have to admit, if even half of his story is true, Eddie Padilla would be the real-life Zelig of America’s late 20th-century drug history. And, as is apparent from his first handshake, he has Clint Eastwood charisma to go with his tale.

I drop Padilla off at one of those high-gloss condo complexes in Woodland Hills that seem designed especially for mid-level rappers, porn stars, and athletes. His son, Eric, manages the place. Though Padilla lives a short flight away in Northern California, he has never been here before. Tonight marks the first time in nine years that he will see his son. For 20 years now, Padilla has been literally and figuratively working on reclaiming his narrative. Reuniting with his son is part of that effort. I may be too, and I’m not sure how I feel about it.

As we approach, Padilla falls silent, unsure of what to expect. Eric is waiting outside the lobby when we pull up. He looks like a younger, slightly smaller version of Padilla. They greet each other with wide smiles and nervous hugs. I leave them to it.

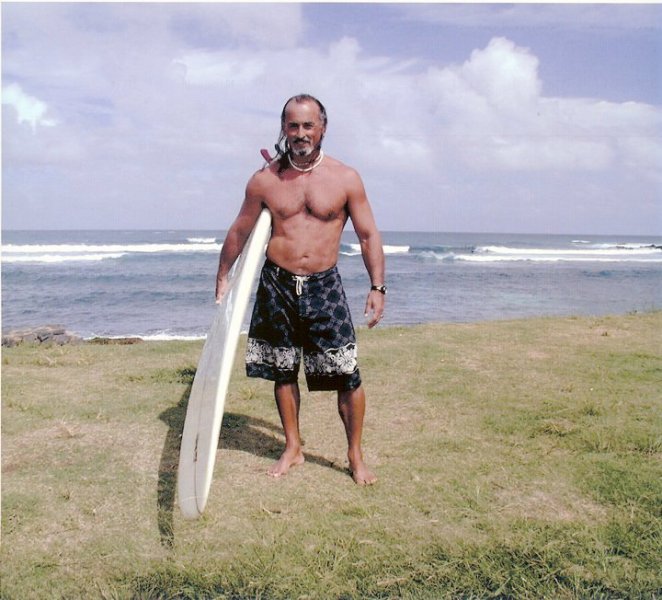

I pick Padilla up the next morning to go surfing. He’s in good spirits. The reunion with his son went well. Plus, he hasn’t been in the water for a while and surfing is one of the few passions left from his earlier days.

Out at County Line, it’s a crystalline day with offshore winds and a decent swell kicking in. For Padilla, I’ve brought my spare board, a big, fancy log that would be cumbersome for most on a head-high day at County Line. Padilla inspects the long board like it’s a foreign object.

“I don’t know about this,” he says. “How about if I take your board and you use this one?” Worried about the danger I’d pose to others and myself, I refuse. “Okay, then,” he smiles, and we paddle out.

Padilla’s reservations disappear as soon as the first set rolls in. He digs for the first wave, a fat, beautifully shaped A-frame. He deftly drops in, stays high on the shoulder, slips into the pocket and makes his way down the line, chewing up every ounce of the wave. It’s one of the best rides I see all day. But he’s not done. Padilla catches wave after wave, surfing with a fluidity and grace that puts most of us out here to shame.

Exhausted after a couple hours, I get out of the water. When Padilla finally comes in, he is grinning ear to ear. “Who’d have thought I’d have to go from Santa Cruz to Los Angeles to find some good waves?” he jokes.

Buoyed by the return to his natural habitat, Padilla lets his guard down and begins to tell me about his life, over lunch at an upscale chain restaurant in Santa Monica. Though Padilla is forty years her senior, the attractive waitress is definitely flirting with him. Whatever it is that makes women melt, Padilla has it. He’s magnetic and likeable. As for his story, it could stand as a metaphor for the past few turbulent decades—the naïve idealism of flower power, the hedonism of the 1970s and ’80s, the psychosis and cynicism of the war on drugs, and the recovery culture of more recent times. It’s a story that’s hard to imagine beginning anywhere but in Southern California

Edward James Padilla was born in 1944 in the same Compton house where his father, Joe Padilla, was raised. Joe, a dashing Navy guy of Hispanic, Native American, and African-American ancestry, married Helen Ruth McClesky, a Scots-Irish beauty from a rough clan of Texas ranch hands who moved to Southern California, near Turlock, during the Dust Bowl.

Both family trees have their troubled histories. Joe’s mother killed herself when Joe was 12. The family broke apart after that and Joe had to fend for himself through the Depression. “He had no idea what it was even like to have a mother,” Padilla says.

Helen’s father turned to moonshining and bootlegging in California. Padilla recalls how his grandfather liked to show off the hole in his leg. As the story goes, Federal agents shot him during a car chase. Padilla raises his leg and imitates his grandfather’s crotchety voice: “That goddamn bullet went through this leg and into that one.”

When his grandfather finally ended up in prison, the family moved down to South Los Angeles where work could be found in the nearby shipyards. Padilla says his mother and father met in high school, “fell desperately in love,” and got married. This didn’t please the old man, who didn’t want his daughter mixing with “Mexicans and niggers.” Helen found both in one.

As the son of a mixed-race couple before such things were in vogue, Padilla got it from all sides. He wasn’t Mexican enough for the Mexicans, white enough for the whites, or black enough for the blacks. He was also a frail kid who spent nine months with polio in a children’s ward.

Padilla would get beaten up at school, and for consolation his father would make him put on boxing gloves and head out to the garage for lessons with dad, a Golden Glove boxer and light heavyweight in the Navy.

“If I turned my back, he’d kick me,” Padilla says about his father, who died in 2001. “He was trying to teach me how to fight the world. My dad was a different kind of guy.”

The family moved to Anaheim when Padilla was 12. There, he says, he became aware of the sort of prejudice that you can’t solve with fists, the sort that keeps a kid from getting a job at Disneyland like the rest of his friends.

“That’s when I started really getting ahold of the idea that, hey, I’m not being treated like everybody else. I’m sure I had a chip on my shoulder.”

Padilla got into a lot of fights, got kicked out of schools and wound up in juvenile hall where he received an education in selling speed, downers, and pot. By the time he was 17, Padilla was making enough as a dealer to afford his own apartment and car. But it wasn’t exactly the good life. He was doing a lot of speed, and one day he got arrested for what must have been an adolescent speed freak’s idea of seduction.

“I started taking handfuls of speed and I got so crazy. I mean, I got arrested for exposing myself to older women because just do that and we’ll have sex. That’s how psychotic I was.”

To make matters worse, he got in a fight with the arresting officer. The incident landed him 13 months at Atascadero State Hospital in San Luis Obispo. He came out feeling like he needed some stability in his life, or at least an 18-year-old’s version of it.

“I need to get married and settle down and be a pot dealer. I remember clearly thinking that. So, I married my friend, Eileen.”

Padilla and Eileen were 18 when they married on August 22, 1962. Marriage, though, didn’t solve certain problems—like how to get a job, which was now even tougher with a stint in a psych ward added to his résumé.

“It would have been really cool if I could walk in somewhere and get a job that actually paid enough to pay rent and live, but from where I was coming from, I’d be lucky to get a job sweeping floors,” he says. “I tried everything. So, it was easy to start selling pot.”

He turned out to be good at it.

Mountain High

Eddie Padilla turned 21 in 1965. Cultural historians wouldn’t declare the arrival of the Summer of Love for a couple of years, but for Padilla and a group of trailblazing friends, it was already in full swing.

He figures he was already the biggest pot dealer in Anaheim by this time. For a kid who grew up watching The Untouchables and dreaming of being a mobster, this might be considered an achievement. But something else was going on, too. The drugs he was selling were getting harder and his lifestyle coarser.

He started sleeping with several women from the apartment complex where he and his wife lived. He spent a lot of time in a notorious tough-guy bar called The Stables. “That’s where I started being comfortable,” Padilla says. “This is where I belonged. Social outcasts for sure.”

Eileen eventually had enough and took off for her mother’s. But it wasn’t just the philandering. Padilla also had an aura of escalating violence about him.

“I had a gun. I felt like I was going down the road to shooting someone, just like hitting someone is a big step for some people. So, that’s kind of insane. I was going to shoot someone just to get it over with. It doesn’t matter who, either.”

Then, early on the morning of his 21st birthday, one of his friends picked him up and drove him to the top of Mount Palomar. Joining them was John Griggs, a Laguna Beach pot dealer and the leader of a biker gang whose introduction to LSD had come when his gang raided a Hollywood producer’s party and took the acid. On the mountain with them were several others who would soon embark on one of the 1960s’ most influential and least understood counterculture experiments, the Brotherhood of Eternal Love. They climbed to the mountaintop and dropped the acid. Padilla says he was changed immediately.

“I was completely convinced that I’d died on that mountain,” he remembers. “It was crystal-clear air, perfect for taking acid. I came down a different person. It was what’s called an ego death. I saw the light. I can’t ever explain it.”

A birthday party was already set with a lot of his old friends for later that night. Back home, in the middle of the celebration Padilla says he looked around at the guests, some of the hardest-partying, toughest folks around, and realized he didn’t ever want to see those people again. He took the velvet painting of the devil off his wall and threw it in the dumpster. He dumped the bowls of reds and bennies laid out like chips and salsa down the toilet. He kept his pot.

“I went up the mountain with no morals or scruples, a very dangerous and violent person,” he says, “and came down with morals and scruples.”

Airs May 22, 2013 - An American hippie turns cocaine smuggler to save his relationship and ends up in a Peruvian hell.

From that day on, a core group of hustlers, dealers, bikers, and surfers, who at best could be said to have lived on the margins of polite society, started convening to take acid together.

“Every time we’d go and take LSD out in nature or out in the desert or up on the mountain, it would be just this incredible wonderful day,” Padilla says. They were transformed, he claims, from tough cases, many of them doing hard drugs, to people with love in their hearts.

Things moved fast back then. The Vietnam War was raging; revolution was in the air, and the group that first started tripping on mountaintops wanted to be a part of it. Under the guidance of John Griggs, by most accounts the spiritual leader of the Brotherhood, they decided they needed to spread their acid-fueled revelations. In the foothills of the Santa Ana Mountains, they took over a Modjeska Canyon house that used to be a church and started having meetings. Soon, they were talking about co-ops and organic living; they were worshipping nature and preaching the gospel of finding peace and love through LSD.

The Brotherhood of Eternal Love incorporated as a church in October 1966, ten days after California banned LSD. The Brothers petitioned the state for the legal use of pot, acid, psilocybin and mescaline as their sacraments. They started a vegan restaurant and gave away free meals. They opened Mystic Arts World, which quickly became the unofficial headquarters for the counterculture movement crystallizing among the surfers and artists of Laguna Beach.

The Brotherhood proved both industrious and ambitious. Soon, they were developing laboratories to cook up a new, better brand of LSD, and opening up unprecedented networks to smuggle tons of hash out of Afghanistan. They were also canny; they carved out the bellies of surfboards and loaded them with pot and hash. They made passport fraud an art form, and became adept at clearing border weigh stations loaded down with surf gear and other disposable weight, which they’d dump on the other side so they could return with the same weight in pot stuffed into hollowed-out VW panel trucks. In their own way, they were the underground rock stars of the psychedelic revolution.

Soon, their skills and chutzpah attracted the attention of another psychedelic revolutionary. By 1967, Timothy Leary was living up in the canyons around Laguna Beach carrying on a symbiotic, some would say parasitic, relationship with Griggs. Leary called Griggs “the holiest man in America,” And more than anyone else, the Brothers implemented Leary’s message to turn on, tune in, drop out.

“The Brotherhood were the folks who actually put that command into action and tried to carry it out,” says Nick Schou, author of Orange Sunshine: The Brotherhood of Eternal Love and Its Quest to Spread Peace, Love, and Acid to the World. “Their home-grown acid, Orange Sunshine, was about three times more powerful than anything the hippies were using. They were responsible for distributing more acid than anyone in America. In the beginning, at least, they had the best of intentions.”

The group, Schou says, was heavily influenced by the utopian ideals of Aldous Huxley’s Island.

“There was a definite plan to move to an island,” Padilla says. “We were going to grow pot on the island and we were going to import it. We need a yacht and we need to learn how to grow food and farm, and we need to learn how to deliver babies . . . We were just little kids from Anaheim. God, these were big thoughts, big thoughts.”

The End of Eternal Love

Around the time Leary was setting up camp in Laguna Beach, the island ideal took on a new urgency for Padilla. No longer just a local dealer, he’d made serious connections in Mexico and was moving large quantities around the region. In one deal, Padilla drove to San Francisco in dense fog with 500 pounds of Mexican weed. But something didn’t feel right. Padilla thought someone might have tipped off the cops. He was right: He was arrested the next day. It was the largest pot bust in San Francisco history to that point. In 1967, Padilla was sentenced to five to fifteen in San Quentin. With his son Eric on the way, Padilla was granted a 30-day stay of execution to get his affairs in order.

“On the thirtieth day, I just left and went to Mexico, went to work for some syndicate guys,” he says. “I bailed.”

Padilla’s flight was also precipitated by a schism within the Brotherhood that some trace to its ultimate demise. Acting on Leary’s advice, Griggs took the profits from a marijuana deal, funds that some Brothers thought should go toward the eventual island purchase, and bought a 400-acre ranch in Idyllwild near Palm Springs.

Padilla never cared much for Leary, nor for his influence over Griggs and the Brotherhood. “He was a glitter freak,” Padilla says. “A guy named Richard Alpert, who became Ram Das, told us, ‘You guys got a good thing going, don’t get mixed up with Leary.’ ”

Padilla saw the Idyllwild incident as a turning point for the Brotherhood. “This is betrayal. This is incredibly stupid. You’re going to move the Brotherhood to a ranch in Idyllwild? To me, it was like becoming a target.”

The Brotherhood split over it. Many of those facing federal indictments or arrest warrants took off for Hawaii. Others moved up to the ranch with Griggs and Leary. As the Brotherhood’s smuggling operations grew increasingly complex and international, revolution started looking increasingly like mercenary capitalism. Any chance the Brotherhood had to retain its cohesion and its gospel probably died in 1969 with John Griggs, who overdosed on psilocybin up at the Ranch.

“That was John,” Padilla says, smiling, “take more than anybody else.”

Not long after, Mystic Arts burned down under mysterious circumstances. It seemed to signal an end, though the Brotherhood would continue to leave its mark on the era. The group masterminded Timothy Leary’s escape from minimum-security Lompoc state prison following his arrest for possession of two kilos of hash and marijuana. Funded by the Brotherhood, the Weather Underground sprung Leary and spirited him and his wife off to Algeria with fake passports.

To facilitate his escape to Mexico, Padilla raised funds from various Brothers and other associates to gain entree with a Mexican pot syndicate run by a kingpin called Papa. His Mexican escapades—busting partners from jail and other adventures—could make their own movie.

One time he drove his truck to the hospital to visit his newborn son, Eric, who was sick with dysentery. On the way, he noticed a woman with a toddler by the side of the road. The kid was foaming at the mouth, the victim of a scorpion bite. Padilla says he threw the boy in the back of his truck and rushed him to the hospital. The doctors told him the kid would have died in another five minutes. They gave him an ambulance sticker for his efforts.

“I put it on my window,” he tells me. “I was driving thousands of pounds of marijuana around in that panel truck. When I’d come to an intersection there would be a cop directing traffic. He’d stop everybody—I’d have a thousand pounds of weed in the back and he’d wave me through because of that ambulance sticker.”

In Mexico, Padilla ran a hacienda for Papa, overseeing the processing and distribution of the pot brought in by local farmers. For more than a year, he skimmed off the best bud and seeds. Meanwhile, he kept alive his dream of sailing to an island.

The dream came true when he and a few associates from the Brotherhood bought a 70-foot yacht in St. Thomas called the Jafje. The Jafje met Padilla in the summer of 1970 in the busy port of Manzanillo. From there, it set sail for Maui.

“It was five guys who had never sailed in their lives,” says Padilla. On board was a ton of the Mexican weed.

The trip should have taken less than two weeks. A month into it, one of the guys onboard, a smuggler with Brotherhood roots named Joe Angeline, noticed the stars weren’t right.

“He said, ‘Eddie, Orion’s belt should be right over our heads.’ But Orion’s belt was way, way south of us. We could barely make it out.”

When confronted, the captain confessed he didn’t know where the hell they were, but had been afraid to tell them. “There’s a hoist that hoists you all the way up to the top of the main mast and we hauled him up there and made him sit there for a day,” says Padilla. “That was funny.”

Eventually, they flagged down a freighter and learned they were more than a 1000 miles off course, dangerously close to the Japanese current. The freighter gave them 300 gallons of fuel and put them back on track to Maui. He’d made it to his island with a load of the finest Mexican marijuana.

“The seeds of that,” Padilla says, “became Maui Wowie.”

Spiritual Warrior

Maui Wowie? The holy grail of my pot-smoking youth, one of the most famous strains of marijuana in history? When Padilla tells me he played a major role in its advent, my already-strained credulity nears the breaking point. I spend months looking into Padilla’s stories, tracking down survivors, digging up what corroborative evidence I can. And, well, he basically checks out. But there are his stories and there is his narrative—how an acid trip on Mount Palomar transformed a 21-year-old borderline sociopath into a man with a purpose, a messenger of peace and love.That one’s harder to swallow. While sitting over coffee at the dining room table in his son’s apartment, Padilla finally tells a couple stories that beg me to challenge him.

Back in the mid-‘60s, he and John Griggs make a deal to purchase a few kilos of pot from a source in Pacoima. They drive out in a station wagon with 18 grand to make the buy. But the sellers burn them and take off with their money in a black Cadillac. The next day, Padilla and spiritual leader Griggs go back armed with a .38 and a .32. Padilla goes into the apartment where the deal was supposed to go down and finds one of the men sleeping on the couch. The guy wakes up and makes for a Winchester rifle sitting near the sink. Padilla runs up behind him and sticks the barrel of his gun in the guy’s ear and says, “Dude, please don’t make me fucking shoot you.” Griggs and Padilla get their money back.

“So, that stuff went on. I’ve been shot at. People have tried to kill me. I’ve had bullets whizzing by my ear,” he says. “But I’ve never had to shoot anybody.”

Padilla tells me of similar episodes in Maui where the locals, understandably, see the influx of the hippie mafia as encroachment on their turf. They set about intimidating the haoles from Laguna, often violently. One newcomer is shot in the head while he sleeps next to his son.

At his house on the Haleakala Crater one night, Padilla opens the door to let in his barking puppy only to find “there’s a guy standing there with a pillow case over his head and holes cut out and the guy behind him was taller and had a pager bag with the holes cut out.”

One of the men has a handgun. Padilla manages to slam the gunman’s hand in the door and chase off the invaders. “I’m going to kill both of you,” he yells after them. “I’m going to find out who you are and kill you.”

Padilla discovers the men work for a hood he knew back in Huntington Beach called Fast Eddie. Like a scene out of a gangster movie, Padilla and Fast Eddie have a showdown when Fast Eddie, in a car full of local muscle, tries to run Padilla and his passenger off the road. They all end up in Lahaina, where Fast Eddie’s henchmen beat up Padilla pretty good before the cops break up the brawl.

“Hey, bra, you no run. Good man,” Padilla recalls the Hawaiians saying to him. When Fast Eddie emerges from the chaos, Padilla points at him and tells the Hawaiians, “I want him. Let me have him.

“I worked him real good and that was that. People robbing and intimidating was over.”

I tell him it doesn’t seem like his life had changed very much since that day on Mount Palomar.

“You know, don’t get the wrong idea,” he laughs. “I’m still who I am. We’re still kind of dangerous people. Just because we were hippies with long hair and preaching love and peace doesn’t mean we became wusses.”

“It doesn’t sound like you had a spiritual awakening to me,” I say.

“I was very spiritual,” he replies. “I thought I was making a life for myself.”

“As what?”

“A warrior. A spiritual warrior.”

“What was your spiritual warring doing? What were you fighting for?”

He falls silent. “I never thought about it before. . . . Remember, I grew up in South Central. I already had an attitude from a young age. So, by the time I got to Maui, it was like, here’s your job, dealing with these people.

“The warrior part was, like, we want to live in Hawaii. We’re not going to accept you guys running our lives. This is what we were trying to get away from. So, my job as a self-motivated warrior was pretty clear, but it’s really difficult to explain.”

“So, your job was protection?” I offer.

“I was never paid.”

It occurs to me that Padilla really wanted to live beyond rules, institutions, and hierarchy, like some romaticized ideal of a pirate. “So why,” I ask, “feel the need to color it with this patina of spirituality? Why not just call it what it was—living young and fast, making money, getting the girls, fucking off authority?”

“Uh, wow . . . I mean, you’re right; it was about all that. It was living fast and really enjoying the lifestyle to the max.”

“Why the need to justify it?”

“Well, it just seemed to me that was what was moving me.”

“It seems that way to you now?”

“Now, yeah now. But then, I felt more, and this sounds really self-righteous, that we were the people who should be in charge, not the ones who were beating people up and taking their stuff and shooting them. So, spiritual warrior, maybe it doesn’t look like that to anyone else, but it sure as hell looks like that to me now.” His voice is soft and intense. “I didn’t have a sign on my head that said spiritual warrior but I definitely felt that’s what was going on . . . . Nobody else was standing up to them. Nobody else would pick up a gun, but I sure as hell would.”

“You have a massive ego,” I suggest.

“Massive.”

“And that’s been your greatness and downfall all along?”

“Sure, yeah, I see that.”

I ask again, amid all the chaos, how his life had improved since his supposed awakening on Mount Palomar.

“My life was incredibly better. I was surfing, sailing, living life. All this other stuff was just, you know . . . I’m not in San Quentin,” he says. “That was the healthiest and clearest time of my life.”

Then, he met Diane Pinnix.

Pinnix was a tall, beautiful girl from Beach Haven, New Jersey, who came of age when Gidget sparked a national surf-culture craze. It’s not surprising that a headstrong girl from New Jersey would catch the bug, and she became one of the original East Coast surfer girls. Legend has it that when Pinnix decided she wanted to get away from New Jersey, she entered a beauty contest on a whim. First prize was a luggage set and a trip to Hawaii. Pinnix, then 18, won.

Pinnix’s mother, Lois, still lives in Beach Haven. When I call her, she has a simple explanation for her daughter’s flight to Hawaii, and her subsequent plight. “It was the times, it was the times. She wanted to spread her wings. Drugs were a part of the thing, but I was very naïve. I was a young mother and in the dark.”

Padilla first ran into Pinnix when he went with a friend looking to score some coke from a local kingpin. Pinnix was the kingpin’s girlfriend. “I looked at Diane and she looked at me and the attraction was so strong,” Padilla recalls. “That was it.”

He started making a point of showing up wherever Pinnix was.

“We’re traveling in the same pack and we started talking and flirting,” says Padilla. “It came to the point of ridiculousness . . . and my own friends were saying, ‘Why don’t you just fuck her and get it over with?’ But that wasn’t it, you know. I wanted her. It was an obsession. A massive ego trip, for sure, but at the same time there was an attraction unlike anything I’d ever experienced before.”

By all accounts, Diane Pinnix, a stunning surfer girl/gun moll, with a nice cutback and blond hair to her ass, was the sort of woman who could make a man do things he hadn’t bargained for.

“One day, we’re getting ready to paddle out, waxing our boards, and I say, ‘So, you want to be my old lady?’ And she says, ‘You have a wife and kids.’ And I say, ‘Okay.’ I was willing to let it go right there and I start to paddle out and she says, ‘But wait a minute.’ And that was it. It was all over. And that’s pretty much when I lost my mind.”

Pinnix was a committed party girl, and Padilla started doing coke and drinking excessively to keep up. After getting iced out of a big deal by a new crew on Maui who claimed Brotherhood status, Padilla decided to go out on his own. He made connections in Colombia and was on his way to becoming a coke smuggler.

“There was no more spiritual warrior,” he says. “This was a guy on his way to hell. I had gone against everything that was precious to me. I left my wife and kids. I wasn’t living the spiritual life I was back when we had the church and it was the Brotherhood of Eternal Love.”

“Why did you do it?” I ask.

“Money. For Diane and me. I probably knew deep inside that if I didn’t have enough money and coke, that she wouldn’t stay with me . . . whether that’s true or not, I’ll never know. The bottom line is I became a coke addict, plain and simple.”

Paradise Lost

A few days before he’s supposed to arrive at Peru’s Gran Azul with Richard Brewer and James Thomason, Eddie Padilla is thousands of miles away on a beach in Tahiti. He sits and looks out at the ocean, contemplating how far things have degenerated, both for him and for the Brotherhood. He thinks about the messages of love, the utopian ideals, and the notion that they could change the world. All that is gone. What is left are the 1970s in all their nihilistic glory. The drugs, money, women, and warring, spiritual or otherwise, are taking their toll, and damn if he isn’t feeling beat already at just 30.

In Tahiti, Padilla at last finds the island paradise that eluded him in Maui. And with Pinnix set up in style on the mainland, it’s a rare moment of peace in his increasingly out-of-control life. He wants more of that.

“It was incredible,” he says. “The best surfing and living, the best food on the planet. While I was in Tahiti, I really got sober and all of the sudden, I was looking at what I’d been doing and I didn’t want to go back.”

Smuggling coke isn’t about peace and love; it’s about money, greed, and power. He suddenly sees his life as a betrayal of his ideals, and he wants out. Feeling something like a premonition, Padilla decides that this next trip to Peru will be his last. Decades later, he remembers the conversation he had with a friend on that Tahitian beach.

“She says to me, ‘What are you doing, how did you get into coke?’ And I just look at her and say, ‘I don’t even know, but I know right now that I don’t want to go back there.” He’s trapped, though. Too much money has already been invested in the deal. “I’m totally responsible and there’s a whole bunch of people involved. But I’ll be back,’ I told her. That was the plan. ‘I’ll be back.’” He books a return flight to Tahiti. He never makes it.

Back at the Gran Azul, just hours before Padilla and his crew are scheduled to leave the country, quasi-military police agents storm the bungalow. One slams Padilla to the floor, another kicks Brewer in the stomach, and quickly Padilla, Brewer, and Thomason are all in cuffs.

“At least 10 or 12 of them come in through the door and they all have guns drawn. I didn’t have a chance,” says Padilla.

A man they will come to know as Sergeant Delgado takes a hollow-point bullet from his gun, starts tapping it against Thomason’s chest, and says, “Tell me everything.”

In some ways, Padilla is a victim of his own success. While he’s been hopping between Hawaii, Tahiti, Colombia, and Peru building his résumé as a coke-smuggling pirate, Richard Nixon has been marshaling his forces for the soon-to-be declared War on Drugs. It’s the beginning of the national hysteria that will see Nixon pronounce the fugitive Timothy Leary “the most dangerous man in America,” and today has more than 2.3 million Americans in prison, a vast majority of them for drug offenses.

Nixon’s strategy in the drug war is announced with his Reorganization Plan No. 2. It calls for the consolidation of the government’s various drug-fighting bureaucracies into the Drug Enforcement Agency. The DEA is formed, at least in part, to do something with Nixon’s boner for the Brotherhood’s members and associates, dubbed “the hippie mafia” in a 1972 Rolling Stone article. Congress holds months of hearings on the need for this new agency in the spring and summer of 1973. One is titled “Hashish Smuggling and Passport Fraud, The Brotherhood of Eternal Love.”

After the DEA starts putting too much heat on his Colombian connections, Padilla sets up shop in Peru. But the DEA’s budget shoots up from $75 to $141 million between 1973 and 1975, and Peru, the world’s largest cocaine-producing country at the time, quickly becomes a client state in the drug war. Some of that DEA money goes to fund and train the notorious Peruvian Investigative Police, or PIP (now called the Peruvian National Police). The PIP operates with near immunity and is expected to get results in the war on drugs.

Sergeant Delgado heads the force. A mean-spirited thug with dead, black eyes, he is one of the most powerful men in Peru. An Interpol agent known as Rubio is with Delgado.

Before the DEA put Peru in its crosshairs, Padilla would have been able to buy out of the arrest. Naturally, his first reaction is to offer up the $58,000 in cash he has with him.

“Don’t worry,” he remembers Rubio telling him. “Don’t say anything about this and when we get to the police station, we’ll work something out.”

The three Americans are taken to the notorious PIP headquarters, known as the Pink Panther, a pink mansion that the police confiscated (they are rumored to have executed the owners). With no tradition of case building, Peruvian detective work at the time pretty much consists of coerced confessions and snitching.

The PIP is famously brutal. During the two weeks the guys are held at Pink Panther, Padilla says they’re surrounded by the sounds of women being raped and men being tortured.

The country’s shaky institutions are rife with corruption, and there is little to no history in Peruvian jurisprudence of due process or jury trials. Prisoners wait for years to have their cases heard before a three-judge tribunal, only to see their fates determined in a matter of minutes. Their arrest immediately throws Padilla, Brewer and Thomason into this Kafkaesque quagmire.

In a 1982 Life magazine story that details the horrors of the Peruvian prison system, and two men who tried to escape it, a survivor tells of his time in the Pink Panther.

My god, I was in tears after they went at me,” Robert B. Holland, a Special Forces Vietnam vet recounts. “I did a couple things in ’Nam I might go to hell for. But Peru was a whole new day.”

When their escape attempt fails, the two primary subjects of the Life story commit suicide by overdosing on sleeping pills. In a final letter to his wife, one of the men, David Treacly, writes, “I have no confidence in either their concept of justice, their methods of interrogation and inconceivable brutality, or in the bumbling incompetence and indifference of our embassy . . . . So, I’m going out tonight . . . . John not only accepts and understands, but has decided he wants to go with me . . . . Given the circumstances, I cannot think of anyone I’d rather go with.”

In this atmosphere of brutality and corruption, Padilla and his friends strike a deal with Delgado. The deal is Delgado will keep the money and the cocaine, probably to resell, and Padilla, Brewer and Thomason will say nothing to the DEA about the drugs or cash—it’s their only leverage. When they go to trial, Delgado is supposed to testify that he never saw the coke on display until he opened a black travel bag. The story will be that a jealous Fastie planted the bag as revenge for Padilla flirting with his girlfriend. With Delgado’s testimony, they are assured, they will be home in six months. In the meantime, though they will have to go to San Juan de Lurigancho prison.

“‘Don’t worry,’” Padilla remembers being told. “‘You’ll be out in four to six months. And the prison is nice. There’s basketball, soccer, a great pool.’”

La Casa Del Diablo

There are, of course, no pools or athletic facilities at Lurigancho. There aren’t even working toilets. Built in the 1960s to house 1,500 inmates, Lurigancho has more than 6,000 by the time Padilla is processed. (Today some estimates put the number of prisoners there at more than 10,000.) Going in, though, Padilla still has an outlaw’s cocky sense of exemption. Besides, he’s paid off his captors.

“It’s just like an adventure,” he remembers thinking. “I’d been in prison. I’d been in jails.”