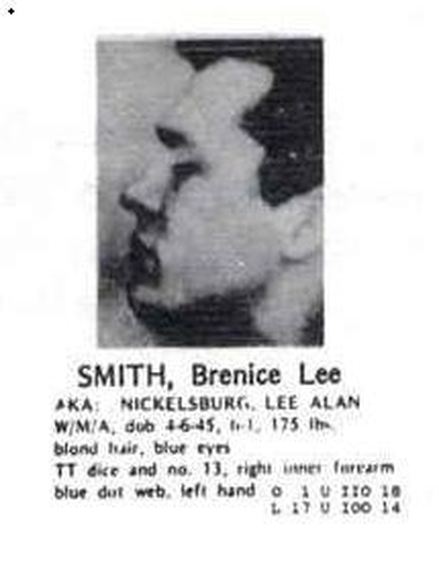

Brenice Smith

Lama On the Lamb - Case Closed

On September 26, 2009 Brenice Lee Smith, a suspected member of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love was arrested in California after nearly four decades on the lam. The 64-year-old Smith was taken into custody at San Francisco International Airport after arriving from Nepal. He was arrested on two, nearly 40-year-old warrants issued in Orange County related to the sale and possession of drugs. On November 20 Smith, after serving two months in jail, pleaded guilty to a single charge of smuggling hashish. Released the next morning, he immediately got back on a plane to live with his wife and daughter in Nepal.

A man accused of of membership in the so-called "Hippie Mafia"--and who has spent the past three decades living a peaceful, possession-free life in a Nepalese monastery--has now been languishing in jail for more than a month.

Brenice Lee Smith was arrested at San Francisco International Airport on Sept. 26 after four decades on the run. A founding member of the Orange County-based Brotherhood of Eternal Love, which formed in 1966 with the intention of promoting peaceful transformation of self and society through consciousness expanding drug experimentation, Smith now stands charged with smuggling 100 pounds of hashish from Afghanistan to California in 1968. After returning from overseas with the intention of moving his Nepalese wife and daughter to the United States, he was extradited from the Bay Area to Orange County's Main Jail.

Many observers who commented on the Weekly's initial blog post, which was picked up by the OC Register, Associated Press and UPI, have expressed shock and amazement that authorities have the time and resources to punish a man who clearly returned to US soil voluntarily and who by all accounts has dedicated himself to peace. Part of the explanation may be that the prosecutor handling the case, Jim Hicks, is the son of DA Cecil Hicks, who presided over the 1972 conspiracy case against the Brotherhood, and who is said to be retiring next March, meaning this case could be his last hurrah.

In the latest developments, Smith had an October 23 hearing in front of Orange County Superior Court Judge William Froeberg, who happens to be married to the chief of the District Attorney's sex crimes unit. Froeberg denied a request by Gerardo Gutierrez, Smith's Chicago-based attorney, to reduce Smith's bail from $1.1 million to $50,000, thus ensuring that his client will remain behind bars for the time being. The next hearings in the case are set for November 7 and December 7. The latter date, Gutierrez said, represents his "drop-dead" deadline for filing a motion to have the case dismissed in the interest of justice.

"Come hell or high water, by December 7, I am going to push this for trial," Gutierrez said. "It will become very apparent that they can't play a shell game anymore." Gutierrez added that the original conspiracy indictment against the Brotherhood was "immaturely drafted," noting that one of the counts actually charged Smith and other Brotherhood members with the supposed crime of living in Laguna Beach. Although Gutierrez has yet to file a motion to dismiss the case, his unsuccessful motion to reduce bail lays out a detailed argument for why that should happen.

First there's the question of whether Smith poses any threat to society.

Here's the answer:

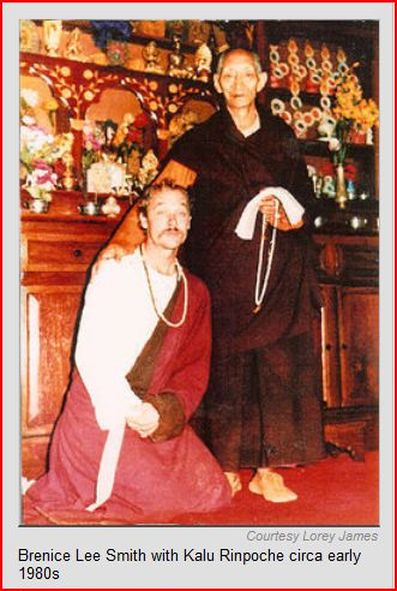

"During his years in exile from these charges, Mr. Smith has lived a sedentary life in the mountainous terrain of Kathmandu, Nepal, where he was carrying on a meager existence as a practicing Buddhist monk, under the tutelage of Kalu Rinpoche, a meditation master, scholar and teacher, one of the first Tibet masters to teach in the West," the motion states. "Smith, remaining in Kathmandu for the petter part of the 80s, 90s, and the first decade of the 21st century, lived a monastic existence where he learned the teachings of Vishnu, the Buddhist practice of philosophical actualization and thee teachings of the Bodhisvatta path, became reborn as a spritual Yogi, or teacher of the path of enlightenment. For our purposes, he became a different person, making correct decisions about his life, marrying a Nepalese woman and fathering a child who is now in her 20s and more importantly, prompting him to return to his home town in California, where authorities were waiting to arrest him."

Second, there's the question of how serious Smith's alleged crimes really were.

On that note, consider the fact that, at the time, smuggling hash could actually get you a life sentence in prison. Possessing merely a joint or two could get you a year in jail. As Gutierrez argues, however, things have changed a bit since then. Nowadays, you can be busted with up to an ounce of marijuana and face no stiffer penalty than a $100 fine--and that's assuming you're one of the dwindling numbers of people who don't have a doctor's note and a state ID card telling the cops to keep their hands off your weed.

Finally there's the question of whether justice would actually be served by punishing Smith, who is now 64 years old.

"Mr. Smith has no ties to any drug activity or any former members in this case," Gutierrez wrote. "Indeed, of the 29 other defendants named in the indictment, ore more precisely the 12 or so individuals specifically alleged to have directly participated with Mr. Smith, all of [them] had their cases dismissed--with prejudice," meaning they can never be recharged.

For his part, Smith had this to say at his Oct. 23 hearing, speaking over the objections of Gutierrez, directly to the judge, apparently hoping he could somehow break the spell of inanity that has pervaded this case since it escaped from the ashbin of history a month ago. "Well," he said. "I've been living in a monastery for the past 30 years. Ten years with in the Lama's house and 20 years in the monastery...I just can't wait to get back to my family."

A man accused of of membership in the so-called "Hippie Mafia"--and who has spent the past three decades living a peaceful, possession-free life in a Nepalese monastery--has now been languishing in jail for more than a month.

Brenice Lee Smith was arrested at San Francisco International Airport on Sept. 26 after four decades on the run. A founding member of the Orange County-based Brotherhood of Eternal Love, which formed in 1966 with the intention of promoting peaceful transformation of self and society through consciousness expanding drug experimentation, Smith now stands charged with smuggling 100 pounds of hashish from Afghanistan to California in 1968. After returning from overseas with the intention of moving his Nepalese wife and daughter to the United States, he was extradited from the Bay Area to Orange County's Main Jail.

Many observers who commented on the Weekly's initial blog post, which was picked up by the OC Register, Associated Press and UPI, have expressed shock and amazement that authorities have the time and resources to punish a man who clearly returned to US soil voluntarily and who by all accounts has dedicated himself to peace. Part of the explanation may be that the prosecutor handling the case, Jim Hicks, is the son of DA Cecil Hicks, who presided over the 1972 conspiracy case against the Brotherhood, and who is said to be retiring next March, meaning this case could be his last hurrah.

In the latest developments, Smith had an October 23 hearing in front of Orange County Superior Court Judge William Froeberg, who happens to be married to the chief of the District Attorney's sex crimes unit. Froeberg denied a request by Gerardo Gutierrez, Smith's Chicago-based attorney, to reduce Smith's bail from $1.1 million to $50,000, thus ensuring that his client will remain behind bars for the time being. The next hearings in the case are set for November 7 and December 7. The latter date, Gutierrez said, represents his "drop-dead" deadline for filing a motion to have the case dismissed in the interest of justice.

"Come hell or high water, by December 7, I am going to push this for trial," Gutierrez said. "It will become very apparent that they can't play a shell game anymore." Gutierrez added that the original conspiracy indictment against the Brotherhood was "immaturely drafted," noting that one of the counts actually charged Smith and other Brotherhood members with the supposed crime of living in Laguna Beach. Although Gutierrez has yet to file a motion to dismiss the case, his unsuccessful motion to reduce bail lays out a detailed argument for why that should happen.

First there's the question of whether Smith poses any threat to society.

Here's the answer:

"During his years in exile from these charges, Mr. Smith has lived a sedentary life in the mountainous terrain of Kathmandu, Nepal, where he was carrying on a meager existence as a practicing Buddhist monk, under the tutelage of Kalu Rinpoche, a meditation master, scholar and teacher, one of the first Tibet masters to teach in the West," the motion states. "Smith, remaining in Kathmandu for the petter part of the 80s, 90s, and the first decade of the 21st century, lived a monastic existence where he learned the teachings of Vishnu, the Buddhist practice of philosophical actualization and thee teachings of the Bodhisvatta path, became reborn as a spritual Yogi, or teacher of the path of enlightenment. For our purposes, he became a different person, making correct decisions about his life, marrying a Nepalese woman and fathering a child who is now in her 20s and more importantly, prompting him to return to his home town in California, where authorities were waiting to arrest him."

Second, there's the question of how serious Smith's alleged crimes really were.

On that note, consider the fact that, at the time, smuggling hash could actually get you a life sentence in prison. Possessing merely a joint or two could get you a year in jail. As Gutierrez argues, however, things have changed a bit since then. Nowadays, you can be busted with up to an ounce of marijuana and face no stiffer penalty than a $100 fine--and that's assuming you're one of the dwindling numbers of people who don't have a doctor's note and a state ID card telling the cops to keep their hands off your weed.

Finally there's the question of whether justice would actually be served by punishing Smith, who is now 64 years old.

"Mr. Smith has no ties to any drug activity or any former members in this case," Gutierrez wrote. "Indeed, of the 29 other defendants named in the indictment, ore more precisely the 12 or so individuals specifically alleged to have directly participated with Mr. Smith, all of [them] had their cases dismissed--with prejudice," meaning they can never be recharged.

For his part, Smith had this to say at his Oct. 23 hearing, speaking over the objections of Gutierrez, directly to the judge, apparently hoping he could somehow break the spell of inanity that has pervaded this case since it escaped from the ashbin of history a month ago. "Well," he said. "I've been living in a monastery for the past 30 years. Ten years with in the Lama's house and 20 years in the monastery...I just can't wait to get back to my family."

Case Closed on Hippie Mafia Smugglers Thu Dec 03, 2009

By Nick Schou

The strange case of the so-called “Hippie Mafia,” the longest, most surreal saga in the annals of American counterculture, is finally over.

On November 20, Brenice Lee Smith, the last remaining fugitive from the legendary band of outlaws known as the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, pleaded guilty to a single charge of smuggling hashish from Afghanistan to Orange County. In return, the Orange County District Attorney's office, which had originally charged Smith with smuggling hash in 1972, dropped all other charges against him. After having spent the previous two months behind bars, Smith left jail a free man early the next morning. He has now returned to his wife and daughter in Nepal, where he has spent the past 30 years.

In an interview shortly after being released, Smith said he returned to California after four decades on the run to be interviewed by a documentary crew making a film about Buddhism. He claimed he spent six years in isolation during his time at a monastery in Darjeeling, India, alongside his guru, the Lama Kalu Rinpoche. Smith's tenure at the monastery ended in the mid-1980s thanks to civil strife at the hands of ethnic Nepalese who were demanding an independent “Gurkaland” state.

Denying that he's had anything to do with drugs since the early 1970s, Smith says that he instead has dedicated his life to constant prayer. “I practice my religion day and night, all the time,” he said. “I sleep very little, maybe three or four hours a day and other than that I sit and pray for the benefit of the world and the people who live in it and my own karma that follows me like a shadow in everything I do. What goes around comes around.”

For his part, Deputy District Attorney Jim Hicks, whose father Cecil Hicks presided over the original Brotherhood conspiracy case, confirmed in an interview outside the courtroom that the Hippie Mafia case is now closed. “That's it,” he said. “We've concluded it.” Hicks added that he had been prepared to go to trial with testimony by former Brotherhood member Travis Ashbrook, who was recently released from prison for growing marijuana, that Smith was "one of the original 13 members of the Brotherhood." According to Hicks, Ashbrook had spoken voluntarily about Smith's involvement with hash smuggling, but had stated that this involvement was minimal.

Reached by telephone at his house near San Diego, however, Ashbrook expressed amazement that Hicks had claimed he'd agreed to testify. "Absolutely not," he said. "I can't believe they said that. There is no way I would have taken the stand. They asked me about Brennie and all I said was that Brennie didn't do anything in the Brotherhood, he wasn't any kind of kingpin and how come you haven't let him out of jail yet?"

"It's clear he wasn't the biggest player," Hicks said of Smith. "If anyone was, it was probably Ashbrook. What he said helped us determine a plea that would adequately describe his conduct and that's what we have."

The Brotherhood was formed in Modjeska Canyon, California in 1966 by a group of mostly high school friends from Anaheim, including Ashbrook and Smith. Many of them were street thugs or heroin addicts but who after dropping acid, found a new sense of spiritual purpose, adopted Eastern religious teachings, became vegetarians, and swore themselves off violence. At the behest of the group's leader, John Griggs, they befriended Timothy Leary with the aim of transforming the world into a peaceful utopia by promoting consciousness-expanding drug experimentation through LSD, including their famous homemade acid, Orange Sunshine.

To finance that goal – becoming America's biggest acid distribution network in the late 1960s and early 1970s – the Brotherhood also became the nation's largest hashish smuggling ring, with a direct pipeline between Kandahar, Afghanistan and Laguna Beach. By the time police finally cracked down on the Brotherhood in 1972, the group was in disarray, a downward spiral that began when Griggs perished of an overdose of synthetic psilocybin in August 1969, an event that Smith witnessed. He says that Griggs immediately realized he'd taken too much and retreated to his teepee with instructions that he not be taken to the hospital, no matter what happened. “He knew he was going to leave his body that night,” Smith says. “He went into convulsions and we put him in the car and by the time he got to the hospital they pronounced him dead.”

Although law enforcement declared victory over the Brotherhood in August 1972 when the largest drug raid in California's history at the time took place, new evidence reveals the group continued to smuggle hashish from Afghanistan for several more years. One of the arrest warrants used to jail Smith when he was arrested at the airport in San Francisco pertained to a smuggling case from 1979, just weeks before the Soviet invasion. Grand jury transcripts from that case show that several Brotherhood members, including Smith, were charged with shipping hashish from the Kandahar-based Tokhi brothers – who had been supplying the Brotherhood since 1967 – after a load was captured by police in the Bay Area. The government's main witness in the case, however, testified that Smith had played virtually no role in that operation, however, other than flying to Kabul, Afghanistan to “build a tennis court” and “visit his goofy guru,” an apparent reference to Rinpoche.

Smith refused to answer any questions about that case or the charges against him, or to talk in detail about the Brotherhood of Eternal Love. “It's all in the past,” he said. “It was not about drugs or LSD or anything like that. We wanted people to be happy and free and not like what society conditioned you to want to be. Basically we loved everyone and wanted everyone to find love and happiness. We wanted to change the world in five years but in five years it changed us. It was an illusion.”

Nick Schou is the author of the [link|http://www.amazon.com/Orange-Sunshine-Brotherhood-Eternal-Spread/dp/0312...|forthcoming book] "Orange Sunshine: The Brotherhood of Eternal Love and Its Quest to Spread Peace, Love and Acid to the World." To read Schou's previous coverage of the Brotherhood, visit [link|http://www.ocweekly.com/|www.ocweekly.com]

By Nick Schou

The strange case of the so-called “Hippie Mafia,” the longest, most surreal saga in the annals of American counterculture, is finally over.

On November 20, Brenice Lee Smith, the last remaining fugitive from the legendary band of outlaws known as the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, pleaded guilty to a single charge of smuggling hashish from Afghanistan to Orange County. In return, the Orange County District Attorney's office, which had originally charged Smith with smuggling hash in 1972, dropped all other charges against him. After having spent the previous two months behind bars, Smith left jail a free man early the next morning. He has now returned to his wife and daughter in Nepal, where he has spent the past 30 years.

In an interview shortly after being released, Smith said he returned to California after four decades on the run to be interviewed by a documentary crew making a film about Buddhism. He claimed he spent six years in isolation during his time at a monastery in Darjeeling, India, alongside his guru, the Lama Kalu Rinpoche. Smith's tenure at the monastery ended in the mid-1980s thanks to civil strife at the hands of ethnic Nepalese who were demanding an independent “Gurkaland” state.

Denying that he's had anything to do with drugs since the early 1970s, Smith says that he instead has dedicated his life to constant prayer. “I practice my religion day and night, all the time,” he said. “I sleep very little, maybe three or four hours a day and other than that I sit and pray for the benefit of the world and the people who live in it and my own karma that follows me like a shadow in everything I do. What goes around comes around.”

For his part, Deputy District Attorney Jim Hicks, whose father Cecil Hicks presided over the original Brotherhood conspiracy case, confirmed in an interview outside the courtroom that the Hippie Mafia case is now closed. “That's it,” he said. “We've concluded it.” Hicks added that he had been prepared to go to trial with testimony by former Brotherhood member Travis Ashbrook, who was recently released from prison for growing marijuana, that Smith was "one of the original 13 members of the Brotherhood." According to Hicks, Ashbrook had spoken voluntarily about Smith's involvement with hash smuggling, but had stated that this involvement was minimal.

Reached by telephone at his house near San Diego, however, Ashbrook expressed amazement that Hicks had claimed he'd agreed to testify. "Absolutely not," he said. "I can't believe they said that. There is no way I would have taken the stand. They asked me about Brennie and all I said was that Brennie didn't do anything in the Brotherhood, he wasn't any kind of kingpin and how come you haven't let him out of jail yet?"

"It's clear he wasn't the biggest player," Hicks said of Smith. "If anyone was, it was probably Ashbrook. What he said helped us determine a plea that would adequately describe his conduct and that's what we have."

The Brotherhood was formed in Modjeska Canyon, California in 1966 by a group of mostly high school friends from Anaheim, including Ashbrook and Smith. Many of them were street thugs or heroin addicts but who after dropping acid, found a new sense of spiritual purpose, adopted Eastern religious teachings, became vegetarians, and swore themselves off violence. At the behest of the group's leader, John Griggs, they befriended Timothy Leary with the aim of transforming the world into a peaceful utopia by promoting consciousness-expanding drug experimentation through LSD, including their famous homemade acid, Orange Sunshine.

To finance that goal – becoming America's biggest acid distribution network in the late 1960s and early 1970s – the Brotherhood also became the nation's largest hashish smuggling ring, with a direct pipeline between Kandahar, Afghanistan and Laguna Beach. By the time police finally cracked down on the Brotherhood in 1972, the group was in disarray, a downward spiral that began when Griggs perished of an overdose of synthetic psilocybin in August 1969, an event that Smith witnessed. He says that Griggs immediately realized he'd taken too much and retreated to his teepee with instructions that he not be taken to the hospital, no matter what happened. “He knew he was going to leave his body that night,” Smith says. “He went into convulsions and we put him in the car and by the time he got to the hospital they pronounced him dead.”

Although law enforcement declared victory over the Brotherhood in August 1972 when the largest drug raid in California's history at the time took place, new evidence reveals the group continued to smuggle hashish from Afghanistan for several more years. One of the arrest warrants used to jail Smith when he was arrested at the airport in San Francisco pertained to a smuggling case from 1979, just weeks before the Soviet invasion. Grand jury transcripts from that case show that several Brotherhood members, including Smith, were charged with shipping hashish from the Kandahar-based Tokhi brothers – who had been supplying the Brotherhood since 1967 – after a load was captured by police in the Bay Area. The government's main witness in the case, however, testified that Smith had played virtually no role in that operation, however, other than flying to Kabul, Afghanistan to “build a tennis court” and “visit his goofy guru,” an apparent reference to Rinpoche.

Smith refused to answer any questions about that case or the charges against him, or to talk in detail about the Brotherhood of Eternal Love. “It's all in the past,” he said. “It was not about drugs or LSD or anything like that. We wanted people to be happy and free and not like what society conditioned you to want to be. Basically we loved everyone and wanted everyone to find love and happiness. We wanted to change the world in five years but in five years it changed us. It was an illusion.”

Nick Schou is the author of the [link|http://www.amazon.com/Orange-Sunshine-Brotherhood-Eternal-Spread/dp/0312...|forthcoming book] "Orange Sunshine: The Brotherhood of Eternal Love and Its Quest to Spread Peace, Love and Acid to the World." To read Schou's previous coverage of the Brotherhood, visit [link|http://www.ocweekly.com/|www.ocweekly.com]

Lawyer for Jailed Brotherhood Figure Demands Dismissal of Case

By Nick Schou Thu., Oct. 29 2009

Wow, that was fast.

Yesterday I blogged that a judge denied a request by Gerardo Gutierrez, the lawyer for Brenice Lee Smith, the onetime member of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love who has spent the past three decades living in a Nepalese monastery, to reduce his client's bail from $1.1 million to $50,000. Smith has now been behind bars for a month, apparently awaiting trial on 40-year-old charges that he conspired to smuggle a bunch of hashish from Afghanistan. In the post I mentioned that Gutierrez hadn't filed a motion to have the charges dismissed but that he planned to do so no later than Dec. 7. I also outlined some common-sense reasons why Smith should be set free immediately.

Today, Gutierrez emailed me a copy of that very motion, which essentially argues that the 1972 conspiracy indictment against Smith and more than two dozen other Brotherhood defendants failed to convincingly charge anybody with any specific crimes, instead simply stating that all of the defendants had conspired to form a church, live in Laguna Beach, deal acid and smuggle hash. (And yes, one of the charges in that indictment really was living in Laguna Beach, and yes, every single person charged in that indictment either pled guilty to lesser charges or had the charges dismissed with prejudice, meaning they can never be refiled).

"Brenice Smith respectfully submits that both of his indictments and all charges thereof should be dismissed with prejudice," the motion states. "In the indictment...there is not any allegation or specifics provided concerning the alleged 'importation, transportation, ale of marijuana (in all its forms) poessession of marijuana for sale, furnish(ing) marijuana to [a] minor, possession of marijuana, sale, transportation, furnishing, manufacturing, administering drugs without prescription, unlawful possession of drugs for sale, possession of drugs without prescription, using a minor as agent or inducing violation by furnishing to a minor, maintaining places for the unlawful disposal of narcotics, possession for purposes of sale of narcotics other than marijuana, transportation, importation, sale, etc., of narcotics other than marijuana, and to commit acts injurious to the public health, to public morals, and to pervert and obstruct justice and due administration of laws."

Whew. Back to Guitierrez' motion.

"Simply stating that someone is involved in in a conspiracy, without more, is exactly the evil that needs to be avoided by at least requiring an assembling of defendants to form a conspiratorial agreement."

In fact, the closest the original Brotherhood indictment now being used to jail Smith actually comes to alleging a specific 'conspiratorial agreement' is when it cites the group's October 1966 articles of incorporation, which were filed in Sacramento about two weeks after the California Legislature banned LSD, becoming the first state to prohibit the drug, and unwittingly turning the Brotherhood of Eternal Love from a (relatively) law abiding group of acid heads into the biggest group of outlaws in the Golden State.

By the way, this is what the Brotherhood of Eternal Love set out to do in those articles of incorporation cited in the indictment in question: "[to] bring the world a greater awareness of God through the teachings of Jesus Christ, Buddha, Ramakrishna, Babaji, Parahamansa Yogananda , Mahatma Gandhi, and all true prophets and apostles of God, and to spread the love and wisdom of these great teachers to all men irrespective of race, color or circumstances."

Thank god the cops put a stop to that.

By Nick Schou Thu., Oct. 29 2009

Wow, that was fast.

Yesterday I blogged that a judge denied a request by Gerardo Gutierrez, the lawyer for Brenice Lee Smith, the onetime member of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love who has spent the past three decades living in a Nepalese monastery, to reduce his client's bail from $1.1 million to $50,000. Smith has now been behind bars for a month, apparently awaiting trial on 40-year-old charges that he conspired to smuggle a bunch of hashish from Afghanistan. In the post I mentioned that Gutierrez hadn't filed a motion to have the charges dismissed but that he planned to do so no later than Dec. 7. I also outlined some common-sense reasons why Smith should be set free immediately.

Today, Gutierrez emailed me a copy of that very motion, which essentially argues that the 1972 conspiracy indictment against Smith and more than two dozen other Brotherhood defendants failed to convincingly charge anybody with any specific crimes, instead simply stating that all of the defendants had conspired to form a church, live in Laguna Beach, deal acid and smuggle hash. (And yes, one of the charges in that indictment really was living in Laguna Beach, and yes, every single person charged in that indictment either pled guilty to lesser charges or had the charges dismissed with prejudice, meaning they can never be refiled).

"Brenice Smith respectfully submits that both of his indictments and all charges thereof should be dismissed with prejudice," the motion states. "In the indictment...there is not any allegation or specifics provided concerning the alleged 'importation, transportation, ale of marijuana (in all its forms) poessession of marijuana for sale, furnish(ing) marijuana to [a] minor, possession of marijuana, sale, transportation, furnishing, manufacturing, administering drugs without prescription, unlawful possession of drugs for sale, possession of drugs without prescription, using a minor as agent or inducing violation by furnishing to a minor, maintaining places for the unlawful disposal of narcotics, possession for purposes of sale of narcotics other than marijuana, transportation, importation, sale, etc., of narcotics other than marijuana, and to commit acts injurious to the public health, to public morals, and to pervert and obstruct justice and due administration of laws."

Whew. Back to Guitierrez' motion.

"Simply stating that someone is involved in in a conspiracy, without more, is exactly the evil that needs to be avoided by at least requiring an assembling of defendants to form a conspiratorial agreement."

In fact, the closest the original Brotherhood indictment now being used to jail Smith actually comes to alleging a specific 'conspiratorial agreement' is when it cites the group's October 1966 articles of incorporation, which were filed in Sacramento about two weeks after the California Legislature banned LSD, becoming the first state to prohibit the drug, and unwittingly turning the Brotherhood of Eternal Love from a (relatively) law abiding group of acid heads into the biggest group of outlaws in the Golden State.

By the way, this is what the Brotherhood of Eternal Love set out to do in those articles of incorporation cited in the indictment in question: "[to] bring the world a greater awareness of God through the teachings of Jesus Christ, Buddha, Ramakrishna, Babaji, Parahamansa Yogananda , Mahatma Gandhi, and all true prophets and apostles of God, and to spread the love and wisdom of these great teachers to all men irrespective of race, color or circumstances."

Thank god the cops put a stop to that.

Brennie with his Nepalese wife and daughter.

Brennie Smith

Was Brotherhood Member Brenice Lee Smith a Felonious Monk?

By NICK SCHOU Thursday, Oct 22 2009 Felonious Monk?

After three decades in Nepal, a fugitive in a hippie-era hash-smuggling case returns to OC in handcuffs

He spent decades on the run, but the last member of the so-called “Hippie Mafia” to evade the long arm of the law, has finally been captured and is now in custody at the Orange County Jail, having pleaded not guilty to 40-year-old charges of hash smuggling and LSD peddling.

Brenice Lee Smith, who grew up in Anaheim, was one of the founding members of the Laguna Beach-based Brotherhood of Eternal Love, a group of hash-smuggling hippies who befriended Timothy Leary and sought to turn on the entire world through their trademark acid, Orange Sunshine (see “Lords of Acid,” July 8, 2005). As the Weekly first reported on our Navel Gazing blog, he was arrested by U.S. Customs agents at San Francisco International Airport on Sept. 26 around 9 p.m., just minutes after arriving from Hong Kong on the second leg of a trip that started a day earlier in Kathmandu, Nepal.

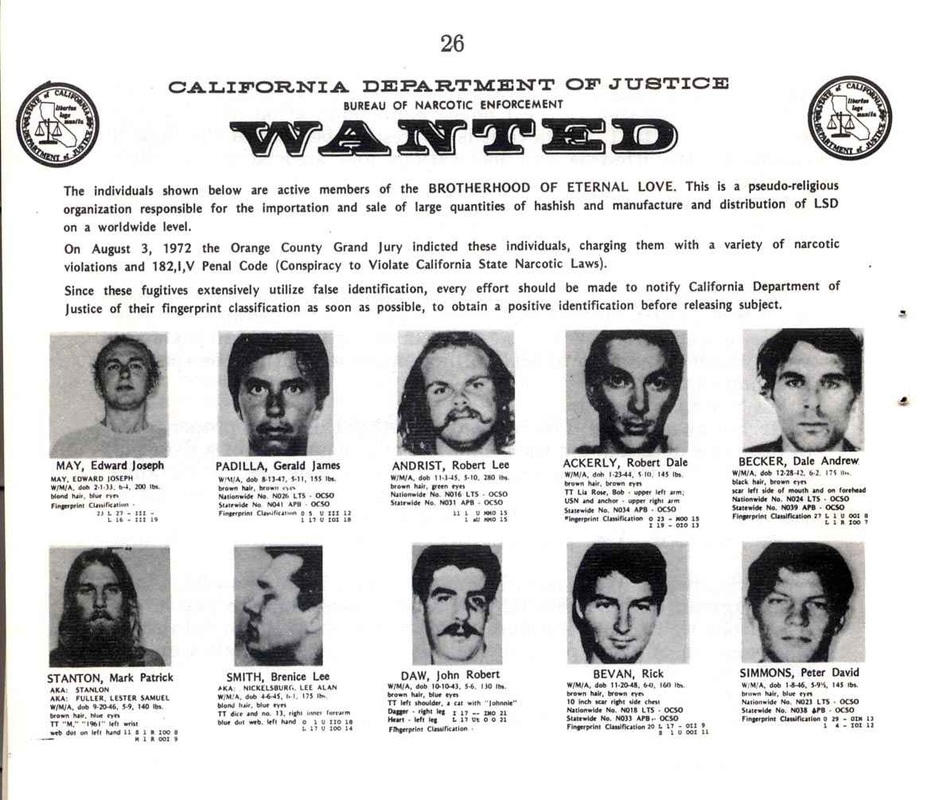

Along with many other members of the Brotherhood, Smith, better-known as “Brennie” among family and friends, allegedly traveled to Kandahar, Afghanistan, in the late 1960s and smuggled hashish back to California inside Volkswagen buses, mobile homes and other vehicles. The Brotherhood distributed more LSD throughout the world than anyone else and famously raised cash with acid sales to bust Leary out of prison and help him escape to Afghanistan, where he was arrested in 1973. Smith was indicted for his role in the group but was among about a dozen members who managed to evade arrest in August 1972 when a task force made up of federal, state and local cops raided Brotherhood houses from Laguna Beach to Oregon to Maui—where many members of the group had fled after OC became too hot—and arrested some 50 people.

The last Brotherhood fugitive to be captured was Orange Sunshine chemist Nicholas Sand, who was arrested in British Columbia in 1996. Sand spent several years in prison for manufacturing LSD. Two years earlier, a friend of Smith’s named Russell Harrigan was arrested by police near Lake Tahoe, California, after they learned his real identity. However, an Orange County judge dismissed the charges against Harrigan because he’d lived a crime-free life while quietly raising a family.

Despite that fact, Deputy District Attorney Jim Hicks says dropping charges against Smith “wasn’t something [he is] considering.” Hicks says the DA’s office is still investigating Smith’s involvement with the Brotherhood, as well as his activities during the past four decades, including his reasons for returning to the United States. “We’re interested in a fair resolution,” Hicks told the Weekly on Oct. 16, just minutes after he told Judge Thomas M. Goethals that he imagined Smith’s trial would take “at least” a month.

Details now emerging about Smith’s life in the past 40 years suggest he has a strong case for having his own charges dismissed. After living underground in California for several years, Smith fled for Nepal in 1981. “He absolutely wanted to go,” says Eddie Padilla, a founding Brotherhood member who is married to Smith’s niece, Lorey James. “He was tired of running around, trying not to get arrested here in the U.S. Then he left and went over to India, then Nepal and lived in the mountains 8,000 feet up in this monastery for five, six, seven or eight years as a shaved-head monk. He fell in love with this guru, Kalu Rinpoche.”

According to Padilla and James, Smith kept in touch with them in frequent letters from Kathmandu, where he moved after Maoist guerrillas began attacking monasteries in the Himalayan foothills. In Kathmandu, Smith—who took the name Dorje with the blessing of Rinpoche—married a Nepalese woman, Rukumani, and fathered a daughter, Anjana, who is now 21 years old.

Recently, James says, her uncle seemed worried about both the mounting political violence in Nepal and his daughter’s future there. “He was starting to get concerned about Anjana,” James says. “He wanted her to be here because the opportunities for her are so vast here compared to any kind of life she could have in Nepal.” So Smith went to the U.S. Embassy in Nepal and applied for a passport under his real name—something he hadn’t done since before smuggling hash in the late 1960s. “He got the passport, and I think he was thinking—and so were we—that if they [the cops] wanted him, that would be the time to get him.”

Both James and Padilla were waiting at the airport to greet Smith, as were William Kirkley, a filmmaker who is working on a documentary about the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, and his co-producer and cinematographer, Rudiger Barth. The filmmakers planned to interview Smith in the Bay Area. Kirkley says he still hopes to interview Smith soon and that the interview won’t be through the bars of a jail cell. “I am hoping they see that [Smith] completely changed his life around, became a Buddhist monk and is much more rehabilitated than he would have been if he had gone to prison,” he says. “We’re all hoping for the best outcome.”

By NICK SCHOU Thursday, Oct 22 2009 Felonious Monk?

After three decades in Nepal, a fugitive in a hippie-era hash-smuggling case returns to OC in handcuffs

He spent decades on the run, but the last member of the so-called “Hippie Mafia” to evade the long arm of the law, has finally been captured and is now in custody at the Orange County Jail, having pleaded not guilty to 40-year-old charges of hash smuggling and LSD peddling.

Brenice Lee Smith, who grew up in Anaheim, was one of the founding members of the Laguna Beach-based Brotherhood of Eternal Love, a group of hash-smuggling hippies who befriended Timothy Leary and sought to turn on the entire world through their trademark acid, Orange Sunshine (see “Lords of Acid,” July 8, 2005). As the Weekly first reported on our Navel Gazing blog, he was arrested by U.S. Customs agents at San Francisco International Airport on Sept. 26 around 9 p.m., just minutes after arriving from Hong Kong on the second leg of a trip that started a day earlier in Kathmandu, Nepal.

Along with many other members of the Brotherhood, Smith, better-known as “Brennie” among family and friends, allegedly traveled to Kandahar, Afghanistan, in the late 1960s and smuggled hashish back to California inside Volkswagen buses, mobile homes and other vehicles. The Brotherhood distributed more LSD throughout the world than anyone else and famously raised cash with acid sales to bust Leary out of prison and help him escape to Afghanistan, where he was arrested in 1973. Smith was indicted for his role in the group but was among about a dozen members who managed to evade arrest in August 1972 when a task force made up of federal, state and local cops raided Brotherhood houses from Laguna Beach to Oregon to Maui—where many members of the group had fled after OC became too hot—and arrested some 50 people.

The last Brotherhood fugitive to be captured was Orange Sunshine chemist Nicholas Sand, who was arrested in British Columbia in 1996. Sand spent several years in prison for manufacturing LSD. Two years earlier, a friend of Smith’s named Russell Harrigan was arrested by police near Lake Tahoe, California, after they learned his real identity. However, an Orange County judge dismissed the charges against Harrigan because he’d lived a crime-free life while quietly raising a family.

Despite that fact, Deputy District Attorney Jim Hicks says dropping charges against Smith “wasn’t something [he is] considering.” Hicks says the DA’s office is still investigating Smith’s involvement with the Brotherhood, as well as his activities during the past four decades, including his reasons for returning to the United States. “We’re interested in a fair resolution,” Hicks told the Weekly on Oct. 16, just minutes after he told Judge Thomas M. Goethals that he imagined Smith’s trial would take “at least” a month.

Details now emerging about Smith’s life in the past 40 years suggest he has a strong case for having his own charges dismissed. After living underground in California for several years, Smith fled for Nepal in 1981. “He absolutely wanted to go,” says Eddie Padilla, a founding Brotherhood member who is married to Smith’s niece, Lorey James. “He was tired of running around, trying not to get arrested here in the U.S. Then he left and went over to India, then Nepal and lived in the mountains 8,000 feet up in this monastery for five, six, seven or eight years as a shaved-head monk. He fell in love with this guru, Kalu Rinpoche.”

According to Padilla and James, Smith kept in touch with them in frequent letters from Kathmandu, where he moved after Maoist guerrillas began attacking monasteries in the Himalayan foothills. In Kathmandu, Smith—who took the name Dorje with the blessing of Rinpoche—married a Nepalese woman, Rukumani, and fathered a daughter, Anjana, who is now 21 years old.

Recently, James says, her uncle seemed worried about both the mounting political violence in Nepal and his daughter’s future there. “He was starting to get concerned about Anjana,” James says. “He wanted her to be here because the opportunities for her are so vast here compared to any kind of life she could have in Nepal.” So Smith went to the U.S. Embassy in Nepal and applied for a passport under his real name—something he hadn’t done since before smuggling hash in the late 1960s. “He got the passport, and I think he was thinking—and so were we—that if they [the cops] wanted him, that would be the time to get him.”

Both James and Padilla were waiting at the airport to greet Smith, as were William Kirkley, a filmmaker who is working on a documentary about the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, and his co-producer and cinematographer, Rudiger Barth. The filmmakers planned to interview Smith in the Bay Area. Kirkley says he still hopes to interview Smith soon and that the interview won’t be through the bars of a jail cell. “I am hoping they see that [Smith] completely changed his life around, became a Buddhist monk and is much more rehabilitated than he would have been if he had gone to prison,” he says. “We’re all hoping for the best outcome.”

Distant Karma Catches Up With the Brotherhood's Brenice Lee Smith

By NICK SCHOU Thursday, Dec 10 2009 Distant Karma

The wheel of life brings Brotherhood of Eternal Love member Brenice Lee Smith back to OC for a brief stay in jail

My passenger for the day walks out of the Best Western Hotel on Pacific Coast Highway in Long Beach. It’s just after 8 a.m. on Nov. 23, the sun is glaring blindingly over the roof of the building, and I have to hold my hand up to shield my eyes. Brenice Lee Smith, 64, closely resembles George Carlin in his later years. He has the same prominent eyebrows and high forehead, and his thin white hair is pulled into a short ponytail. But there the similarity ends: Smith is wearing a yellow smock, a bright-orange cotton jacket and a maroon robe, all of which, I gather, constitute the standard attire of a practicing Buddhist from Nepal.

Smith shakes my hand and introduces himself as “Dorje,” the name given to him by his Tibetan guru, the great Lama Kalu Rinpoche, many years ago at a monastery in Darjeeling, India, in the foothills of the Himalayas. Dorje means “diamond” or “thunderbolt” in Tibetan—the word also can refer to the ceremonial scepter held in their right hand by lamas—and the moniker is clearly a great honor for Smith, whose somewhat unusual first name rhymes with Dennis and who is better known by his friends and family simply as Brennie.

This morning, I am acting as chauffeur for Smith, who does not drive. He has to be at John Wayne Airport by 12:30 p.m., and before that, he has a date at the Orange County Superior Courthouse. Specifically, Smith must present himself at the DNA collection room on the second floor to provide the court with a sample of his genetic makeup by swabbing the inside of his cheek with a plastic scraper.

As he sits down in the front passenger seat of my four-door sedan, his niece, Lorey James, who is sitting in the back seat, reminds him to put on his seat belt. “It’s the law,” she adds.

“Ah, yes,” Smith says. “Seat belts.”

A puzzled expression forms on his face as he cocks his head from one angle to another, struggling to figure out how to work the device. Helplessly, he lifts his right arm up in the air while his other hand pulls in vain on the buckle clasp on the left side of his seat, the part of the assemblage that doesn’t stretch because it’s anchored to the floor. “I really don’t understand these things,” he finally says. “How does this work?”

* * *

This is only the third time that Smith has ever worn a seat belt. As a kid growing up in Buena Park in the 1950s and later, as a member of the Laguna Beach-based band of acid-dropping hippie drug smugglers known as the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, he never wore one, he says, and by the time they became mandatory for automobile passengers in California in the mid-1980s, he was long gone, a fugitive of the first major skirmish in America’s seemingly eternal so-called “War On Drugs.” The last time he set foot in Orange County, Jimmy Carter was in the White House and the Bee Gees topped the charts. He only came home a few months ago, and he’s already eager to get out of the country.

The last time Smith wore a seat belt was a few nights before I met him, shortly after midnight, when he got a ride from Theo Lacy Men’s Jail to his Long Beach hotel room, with a quick detour to a fast-food restaurant in Newport Beach. After decades away from Southern California, the first meal Smith wanted when he got out of jail was a cheeseburger. Driving the car that night was William Kirkley, a filmmaker working on a documentary about the Brotherhood of Eternal Love called Orange Sunshine, and his director of photography Rudiger Barth, both of whom were more than happy to oblige Smith’s request by driving him to an In-N-Out.

“You really ought to get the double-double,” Kirkley had suggested as they sat in the drive-through lane. (Full disclosure: I’ve provided research assistance for Orange Sunshine.) Smith, not knowing what the hell that meant, gruffly insisted he just wanted a simple cheeseburger. They drove to the beach at the end of the Balboa Peninsula for an impromptu, celebratory picnic. After he wolfed down his burger, Smith, still hungry, sighed with wistful resignation. “You’re right,” he muttered. “I should have gotten the double-double.”

Before that night, the only other time in his life that Smith had worn a seat belt was two months ago when, along with a pair of prostitutes and another male prisoner, he sat handcuffed in the back of a police van on a several-hours-long journey from the San Mateo County Jail to the Orange County Men’s Jail. Three days earlier, at about 9 p.m. on Sept. 26, he had been arrested at the San Francisco International Airport after arriving on a flight from his home in Kathmandu, setting foot on American soil for the first time since 1979.

By NICK SCHOU Thursday, Dec 10 2009 Distant Karma

The wheel of life brings Brotherhood of Eternal Love member Brenice Lee Smith back to OC for a brief stay in jail

My passenger for the day walks out of the Best Western Hotel on Pacific Coast Highway in Long Beach. It’s just after 8 a.m. on Nov. 23, the sun is glaring blindingly over the roof of the building, and I have to hold my hand up to shield my eyes. Brenice Lee Smith, 64, closely resembles George Carlin in his later years. He has the same prominent eyebrows and high forehead, and his thin white hair is pulled into a short ponytail. But there the similarity ends: Smith is wearing a yellow smock, a bright-orange cotton jacket and a maroon robe, all of which, I gather, constitute the standard attire of a practicing Buddhist from Nepal.

Smith shakes my hand and introduces himself as “Dorje,” the name given to him by his Tibetan guru, the great Lama Kalu Rinpoche, many years ago at a monastery in Darjeeling, India, in the foothills of the Himalayas. Dorje means “diamond” or “thunderbolt” in Tibetan—the word also can refer to the ceremonial scepter held in their right hand by lamas—and the moniker is clearly a great honor for Smith, whose somewhat unusual first name rhymes with Dennis and who is better known by his friends and family simply as Brennie.

This morning, I am acting as chauffeur for Smith, who does not drive. He has to be at John Wayne Airport by 12:30 p.m., and before that, he has a date at the Orange County Superior Courthouse. Specifically, Smith must present himself at the DNA collection room on the second floor to provide the court with a sample of his genetic makeup by swabbing the inside of his cheek with a plastic scraper.

As he sits down in the front passenger seat of my four-door sedan, his niece, Lorey James, who is sitting in the back seat, reminds him to put on his seat belt. “It’s the law,” she adds.

“Ah, yes,” Smith says. “Seat belts.”

A puzzled expression forms on his face as he cocks his head from one angle to another, struggling to figure out how to work the device. Helplessly, he lifts his right arm up in the air while his other hand pulls in vain on the buckle clasp on the left side of his seat, the part of the assemblage that doesn’t stretch because it’s anchored to the floor. “I really don’t understand these things,” he finally says. “How does this work?”

* * *

This is only the third time that Smith has ever worn a seat belt. As a kid growing up in Buena Park in the 1950s and later, as a member of the Laguna Beach-based band of acid-dropping hippie drug smugglers known as the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, he never wore one, he says, and by the time they became mandatory for automobile passengers in California in the mid-1980s, he was long gone, a fugitive of the first major skirmish in America’s seemingly eternal so-called “War On Drugs.” The last time he set foot in Orange County, Jimmy Carter was in the White House and the Bee Gees topped the charts. He only came home a few months ago, and he’s already eager to get out of the country.

The last time Smith wore a seat belt was a few nights before I met him, shortly after midnight, when he got a ride from Theo Lacy Men’s Jail to his Long Beach hotel room, with a quick detour to a fast-food restaurant in Newport Beach. After decades away from Southern California, the first meal Smith wanted when he got out of jail was a cheeseburger. Driving the car that night was William Kirkley, a filmmaker working on a documentary about the Brotherhood of Eternal Love called Orange Sunshine, and his director of photography Rudiger Barth, both of whom were more than happy to oblige Smith’s request by driving him to an In-N-Out.

“You really ought to get the double-double,” Kirkley had suggested as they sat in the drive-through lane. (Full disclosure: I’ve provided research assistance for Orange Sunshine.) Smith, not knowing what the hell that meant, gruffly insisted he just wanted a simple cheeseburger. They drove to the beach at the end of the Balboa Peninsula for an impromptu, celebratory picnic. After he wolfed down his burger, Smith, still hungry, sighed with wistful resignation. “You’re right,” he muttered. “I should have gotten the double-double.”

Before that night, the only other time in his life that Smith had worn a seat belt was two months ago when, along with a pair of prostitutes and another male prisoner, he sat handcuffed in the back of a police van on a several-hours-long journey from the San Mateo County Jail to the Orange County Men’s Jail. Three days earlier, at about 9 p.m. on Sept. 26, he had been arrested at the San Francisco International Airport after arriving on a flight from his home in Kathmandu, setting foot on American soil for the first time since 1979.

The first indication that Smith’s return from decades-long exile wouldn’t be so simple materialized in the form of a pair of uniformed San Francisco police officers who were waiting just outside the airplane. As the two passengers in front of him walked past the officers, one of the cops motioned toward Smith. “Come with us, please,” he said. “You’re under arrest.”

The cops informed Smith he was wanted on two charges of smuggling hashish from Afghanistan to Orange County nearly 40 years ago. Smith refused to answer any questions, except to say he had returned home to be interviewed for a documentary about Buddhism. During the next two months Smith spent behind bars, first at the Orange County Jail and then at Theo Lacy, he maintained his silence. All the other inmates appeared to know he was once part of the so-called “Hippie Mafia,” and they were cool with that. Nobody gave him a hard time. In fact, as Smith tells it, all the inmates appeared to regard him with great esteem.Occasionally, a guard would ask him if he knew Timothy Leary. “You know that’s why you’re here, right?” they’d joke.

“Oh, I knew Timothy 40 years ago,” Smith would respond.

One night, a mysterious stranger visited Smith at the Orange County Jail and asked him about Leary as well.

“Yes, I knew Timothy Leary, but that was 40 years ago,” Smith recited.

Undeterred, the man asked Smith whether he knew someone named John Griggs.

“John Griggs? Who’s that?” Smith responded.

“He was the leader of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love,” the agent replied. “Weren’t you in the Brotherhood?”

Smith recalls pondering the broad, philosophical dimension of that question for a few moments. “Well, everyone is part of the Brotherhood as far as I know,” he finally answered. “It’s a world of Brotherhood: Everybody’s been our father and mother, and everyone’s been our uncles and aunts.” He refused to answer any more questions.

The agent, whoever he was—the Orange County Sheriff’s Department put a black line across the name of his employer before releasing Smith’s visitor log to the Weekly—left empty-handed.

* * *

Brenice Lee Smith’s long, strange trip from Orange County to the Far East and back began 43 years ago in a stone building on the steep slope of a heavily wooded property nestled in Modjeska Canyon. Renting the house was the aforementioned John Griggs, a 21-year-old recovering heroin addict and petty crook who had moved there with his young wife, Carol, from Anaheim. The stone house was known as “the church,” and it was there, in October 1966, on the screened upstairs back porch, that Smith (who was also 21 years old at the time), Griggs and about a dozen of their closest friends formed a church called the Brotherhood of Eternal Love.

The purpose of the church, according to legal paperwork the group filed in Sacramento, was to “bring the world a greater awareness of God through the teachings of Jesus Christ, Buddha, Ramakrishna, Babaji, Paramahansa Yogananda, Mahatma Gandhi, and all true prophets and apostles of God, and to spread the love and wisdom of these great teachers to all men irrespective of race, color or circumstances.” The Brotherhood’s sacrament of choice, lysergic acid diethylamide—or LSD, also known as acid—had just been made illegal in California. The fortuitous timing of this prohibition helped steer Griggs and his cohorts into the most organized and evangelical band of outlaws in the state.

Dubbed the “Hippie Mafia” by police and, later, Rolling Stone Magazine, the Brotherhood was famous for its headquarters, Mystic Arts World, a head shop, clothing boutique, art gallery and psychedelic reading room on PCH across the street from a Taco Bell. The street corner became infamous as the center of Southern California’s drug scene, where teenagers from as far away as Pasadena and San Diego knew they could find acid, marijuana or hashish (see “Lords of Acid,” July 7, 2005). The group lived nearby in a warren of clapboard shacks on Woodland Drive in Laguna Canyon, just a stone’s throw from the current location of the Sawdust Festival, in a neighborhood known as “Dodge City” for the density of drug dealers who lived there and the frequent raids by all manner of law-enforcement agencies.

The Brotherhood even lured Leary, who had famously commanded the world to “turn on, tune in and drop out,” to Laguna Beach, where he became something of a high priest for the group, even though he considered Griggs to be his guru and the “holiest man who has ever lived in this country.” Although the Brotherhood had talked about buying a tropical island where they could create an experimental utopia, Leary had no interest in abandoning civilization, and Griggs ended up hosting Leary at a more modest commune in the mountains above Idyllwild, near Palm Springs. There, several members of the Brotherhood, including Smith, lived in tepees, grew their own vegetables, delivered their own babies and dropped a lot of acid.

The cops informed Smith he was wanted on two charges of smuggling hashish from Afghanistan to Orange County nearly 40 years ago. Smith refused to answer any questions, except to say he had returned home to be interviewed for a documentary about Buddhism. During the next two months Smith spent behind bars, first at the Orange County Jail and then at Theo Lacy, he maintained his silence. All the other inmates appeared to know he was once part of the so-called “Hippie Mafia,” and they were cool with that. Nobody gave him a hard time. In fact, as Smith tells it, all the inmates appeared to regard him with great esteem.Occasionally, a guard would ask him if he knew Timothy Leary. “You know that’s why you’re here, right?” they’d joke.

“Oh, I knew Timothy 40 years ago,” Smith would respond.

One night, a mysterious stranger visited Smith at the Orange County Jail and asked him about Leary as well.

“Yes, I knew Timothy Leary, but that was 40 years ago,” Smith recited.

Undeterred, the man asked Smith whether he knew someone named John Griggs.

“John Griggs? Who’s that?” Smith responded.

“He was the leader of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love,” the agent replied. “Weren’t you in the Brotherhood?”

Smith recalls pondering the broad, philosophical dimension of that question for a few moments. “Well, everyone is part of the Brotherhood as far as I know,” he finally answered. “It’s a world of Brotherhood: Everybody’s been our father and mother, and everyone’s been our uncles and aunts.” He refused to answer any more questions.

The agent, whoever he was—the Orange County Sheriff’s Department put a black line across the name of his employer before releasing Smith’s visitor log to the Weekly—left empty-handed.

* * *

Brenice Lee Smith’s long, strange trip from Orange County to the Far East and back began 43 years ago in a stone building on the steep slope of a heavily wooded property nestled in Modjeska Canyon. Renting the house was the aforementioned John Griggs, a 21-year-old recovering heroin addict and petty crook who had moved there with his young wife, Carol, from Anaheim. The stone house was known as “the church,” and it was there, in October 1966, on the screened upstairs back porch, that Smith (who was also 21 years old at the time), Griggs and about a dozen of their closest friends formed a church called the Brotherhood of Eternal Love.

The purpose of the church, according to legal paperwork the group filed in Sacramento, was to “bring the world a greater awareness of God through the teachings of Jesus Christ, Buddha, Ramakrishna, Babaji, Paramahansa Yogananda, Mahatma Gandhi, and all true prophets and apostles of God, and to spread the love and wisdom of these great teachers to all men irrespective of race, color or circumstances.” The Brotherhood’s sacrament of choice, lysergic acid diethylamide—or LSD, also known as acid—had just been made illegal in California. The fortuitous timing of this prohibition helped steer Griggs and his cohorts into the most organized and evangelical band of outlaws in the state.

Dubbed the “Hippie Mafia” by police and, later, Rolling Stone Magazine, the Brotherhood was famous for its headquarters, Mystic Arts World, a head shop, clothing boutique, art gallery and psychedelic reading room on PCH across the street from a Taco Bell. The street corner became infamous as the center of Southern California’s drug scene, where teenagers from as far away as Pasadena and San Diego knew they could find acid, marijuana or hashish (see “Lords of Acid,” July 7, 2005). The group lived nearby in a warren of clapboard shacks on Woodland Drive in Laguna Canyon, just a stone’s throw from the current location of the Sawdust Festival, in a neighborhood known as “Dodge City” for the density of drug dealers who lived there and the frequent raids by all manner of law-enforcement agencies.

The Brotherhood even lured Leary, who had famously commanded the world to “turn on, tune in and drop out,” to Laguna Beach, where he became something of a high priest for the group, even though he considered Griggs to be his guru and the “holiest man who has ever lived in this country.” Although the Brotherhood had talked about buying a tropical island where they could create an experimental utopia, Leary had no interest in abandoning civilization, and Griggs ended up hosting Leary at a more modest commune in the mountains above Idyllwild, near Palm Springs. There, several members of the Brotherhood, including Smith, lived in tepees, grew their own vegetables, delivered their own babies and dropped a lot of acid.

Meanwhile, beginning in 1967 and expanding over the course of the next several years, the Brotherhood became not only America’s biggest acid distribution network, complete with its own brand of legendarily intense LSD, Orange Sunshine, but also the nation’s most prodigious group of hashish smugglers. Brotherhood smugglers flew to Europe; purchased Volkswagen buses, Land Rovers and other vehicles; drove them overland to Kandahar, Afghanistan—later to become the birthplace of the Taliban—and then shipped them home to California from Karachi, Pakistan.

It all came crashing to a halt at dawn on Aug. 5, 1972. In the largest narcotics raid that had ever taken place in California, police from Laguna Beach to Oregon to Maui to Kabul, Afghanistan, raided dozens of houses and arrested 53 people. One of them was founding Brotherhood member Glenn Lynd, who’d lived at the ranch with Leary, Griggs and Smith, but had fallen out with the group. After moving to Grants Pass, Oregon, Lynd had boasted about the Brotherhood’s exploits to his brother-in-law, Robert Ramsey, who, unbeknownst to Lynd, had been busted for selling speed and become an undercover informant for the Josephine County Sheriff’s Department.

To the surprise of everyone who knew him, including Smith, Lynd agreed to cooperate against the Brotherhood. Over the course of several days, Lynd told members of the Orange County grand jury everything he knew about the group—how it had formed, how acid had been viewed as a tool of cosmic mind-expansion that could bring peace and love to the world, how Leary had come into their orbit, and, more to the point, how they’d smuggled all that hashish into the country.

Lynd had been on only one smuggling trip to Afghanistan in 1968. His partner in the adventure: Brenice Lee Smith.

* * *

Testifying under oath, Lynd described how he and Smith had flown to Germany, purchased a Volkswagen van and driven it to Kandahar, where they met up with two merchants who a year earlier had procured hashish for the first Brotherhood smugglers to reach Afghanistan, Rick Bevan and Travis Ashbrook. By the time they met the merchants, however, Lynd was sick with dysentery, and the pair were flat-broke. To save the deal, Ashbrook flew to Kandahar, sent Lynd home wearing a jacket lined with hash and instructions to sell the drug to a trusted friend and wire the proceeds to Karachi, where Ashbrook used the cash to ship the Volkswagen to Los Angeles.

Lynd did as instructed, and shortly after Ashbrook and Smith flew home, the Volkswagen, along with a few hundred pounds of hash, arrived safely at the Port of Los Angeles. According to Lynd, he and Smith drove to the port to pick up the vehicle. After filling out some forms and getting the keys to the bus, they were directed to another building for an impromptu inspection. Terrified, they drove the Volkswagen toward the inspection site, but before they reached it, they noticed an unguarded gate with a freeway on-ramp just beyond it. They left the port and drove straight to a safe house in the desert where they unloaded the hash.

By the time Lynd betrayed the Brotherhood four years later, the group had already imploded, at least in part thanks to the rise of cocaine, which had turned several members into addicts and perverted the idealism of the group’s spiritual origins. The Brotherhood had also suffered the loss of its most charismatic member, Griggs, who in August 1969 died of an overdose of synthetic psilocybin at the ranch near Idyllwild. In 1970, Leary, who had been jailed in a Laguna Beach pot-possession case, escaped from prison with the Brotherhood’s help. He made his way to Kabul, where he was arrested several months after Lynd spilled the beans (see “OC’s Brotherly Connection With the Weathermen,” Sept. 16, 2009).

The last Brotherhood fugitives were captured 15 years ago. Police found smuggler Russell Harrigan near Lake Tahoe, living under an assumed name; a judge promptly dismissed all charges against him. Two years later, the cops nabbed Orange Sunshine chemist Nick Sand, who was still operating a clandestine laboratory in British Columbia. Sand spent the next six years behind bars.

Nobody in the Brotherhood of Eternal Love lived on the run nearly as long as Smith. Because he was indicted in 1972 but never arrested or jailed, Smith still had two warrants out for his arrest when he returned to California nearly 40 years later.

After Smith had spent two months behind bars awaiting trial, the Orange County district attorney’s office seemed to have realized it didn’t have much of a case against him. Lynd, the main witness in the 1972 conspiracy case, died of cancer in 2002 and was therefore unavailable to testify. Their next-best hope was Travis Ashbrook, who had just been released from prison after serving nearly a year behind bars for a large marijuana-growing operation at his house near Temecula. (After living on the run for several years, Ashbrook was caught in 1980; he spent the next decade in prison for smuggling hash from Lebanon.)

It all came crashing to a halt at dawn on Aug. 5, 1972. In the largest narcotics raid that had ever taken place in California, police from Laguna Beach to Oregon to Maui to Kabul, Afghanistan, raided dozens of houses and arrested 53 people. One of them was founding Brotherhood member Glenn Lynd, who’d lived at the ranch with Leary, Griggs and Smith, but had fallen out with the group. After moving to Grants Pass, Oregon, Lynd had boasted about the Brotherhood’s exploits to his brother-in-law, Robert Ramsey, who, unbeknownst to Lynd, had been busted for selling speed and become an undercover informant for the Josephine County Sheriff’s Department.

To the surprise of everyone who knew him, including Smith, Lynd agreed to cooperate against the Brotherhood. Over the course of several days, Lynd told members of the Orange County grand jury everything he knew about the group—how it had formed, how acid had been viewed as a tool of cosmic mind-expansion that could bring peace and love to the world, how Leary had come into their orbit, and, more to the point, how they’d smuggled all that hashish into the country.

Lynd had been on only one smuggling trip to Afghanistan in 1968. His partner in the adventure: Brenice Lee Smith.

* * *

Testifying under oath, Lynd described how he and Smith had flown to Germany, purchased a Volkswagen van and driven it to Kandahar, where they met up with two merchants who a year earlier had procured hashish for the first Brotherhood smugglers to reach Afghanistan, Rick Bevan and Travis Ashbrook. By the time they met the merchants, however, Lynd was sick with dysentery, and the pair were flat-broke. To save the deal, Ashbrook flew to Kandahar, sent Lynd home wearing a jacket lined with hash and instructions to sell the drug to a trusted friend and wire the proceeds to Karachi, where Ashbrook used the cash to ship the Volkswagen to Los Angeles.

Lynd did as instructed, and shortly after Ashbrook and Smith flew home, the Volkswagen, along with a few hundred pounds of hash, arrived safely at the Port of Los Angeles. According to Lynd, he and Smith drove to the port to pick up the vehicle. After filling out some forms and getting the keys to the bus, they were directed to another building for an impromptu inspection. Terrified, they drove the Volkswagen toward the inspection site, but before they reached it, they noticed an unguarded gate with a freeway on-ramp just beyond it. They left the port and drove straight to a safe house in the desert where they unloaded the hash.

By the time Lynd betrayed the Brotherhood four years later, the group had already imploded, at least in part thanks to the rise of cocaine, which had turned several members into addicts and perverted the idealism of the group’s spiritual origins. The Brotherhood had also suffered the loss of its most charismatic member, Griggs, who in August 1969 died of an overdose of synthetic psilocybin at the ranch near Idyllwild. In 1970, Leary, who had been jailed in a Laguna Beach pot-possession case, escaped from prison with the Brotherhood’s help. He made his way to Kabul, where he was arrested several months after Lynd spilled the beans (see “OC’s Brotherly Connection With the Weathermen,” Sept. 16, 2009).

The last Brotherhood fugitives were captured 15 years ago. Police found smuggler Russell Harrigan near Lake Tahoe, living under an assumed name; a judge promptly dismissed all charges against him. Two years later, the cops nabbed Orange Sunshine chemist Nick Sand, who was still operating a clandestine laboratory in British Columbia. Sand spent the next six years behind bars.

Nobody in the Brotherhood of Eternal Love lived on the run nearly as long as Smith. Because he was indicted in 1972 but never arrested or jailed, Smith still had two warrants out for his arrest when he returned to California nearly 40 years later.

After Smith had spent two months behind bars awaiting trial, the Orange County district attorney’s office seemed to have realized it didn’t have much of a case against him. Lynd, the main witness in the 1972 conspiracy case, died of cancer in 2002 and was therefore unavailable to testify. Their next-best hope was Travis Ashbrook, who had just been released from prison after serving nearly a year behind bars for a large marijuana-growing operation at his house near Temecula. (After living on the run for several years, Ashbrook was caught in 1980; he spent the next decade in prison for smuggling hash from Lebanon.)

As we walk out of the courthouse 15 minutes and a few DNA-carrying cells later, I ask Smith how he feels now that it’s all over, now that his life on the run has officially come to a close. Until now, I hadn’t been sure he’d agree to answer any of my questions on the record, but because I’d helped him avoid wasting even more time in the courthouse, Smith allows me to turn on my tape recorder.

“I feel basically the same,” he says. “Not any better, not any worse, just an ordinary day, coming and going, in one door and out the other.” We get in my car for the drive to the airport, and I hand my tape recorder to Smith so I can steer with two hands. He hands it back as he resigns himself to the challenge of buckling his seat belt again. “I really am not used to these safety belts,” he admits.

I try to ask Smith about the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, but he balks. “That’s all in the past,” he says as we leave the courthouse parking structure. “I live in the present.” Finally, Smith agrees to tell me what the Brotherhood tried to accomplish. “It was not about drugs or LSD or anything like that,” he says. “We wanted people to be happy and free and not like what society conditioned you to want to be. Basically, we loved everyone and wanted everyone to find love and happiness. We wanted to change the world in five years, but in five years, it changed us. It was an illusion.”

He still recalls the night Griggs died from his overdose of psilocybin. “He just took some, and as soon as he took it, he realized he had taken too much.” Griggs wandered back into his tepee and asked his wife not to take him to the hospital. “He knew he was going to leave his body that night,” Smith says. “He went into convulsions, and we put him in the car, and by the time he got to the hospital, they pronounced him dead.”

Happier memories include the time the Moody Blues showed up at the ranch to meet Leary, but they dropped so much acid they never got around to it, and how he and another Brotherhood member visited Mick Jagger and Keith Richards in their hotel room in Hollywood. “We smoked and hung out with them that evening and never saw them again,” he says. “They were aware of the Brotherhood but didn’t want to go to the ranch. Mick Jagger was nervous and thought we’d bring them trouble, and he was in enough trouble as it was with the different police departments all over the United States and Europe that wanted to bust him.”

As we reach the airport, Smith rushes to finish telling me how he spent the past 30 years of his life. He met his guru, Lama Kalu Rinpoche, at a Buddhist retreat in Palm Springs, about five years after becoming a fugitive. He followed Rinpoche from California to Maui to Darjeeling, India, where he spent the next 11 years living at Rinpoche’s monastery. Half that time, he lived in isolation, praying, “om mani padme hum” 100 million times. He befriended a quiet Norwegian, a fellow devotee of Rinpoche, who turned out to be extremely wealthy and who offered to sponsor Smith for the rest of his life if he continued to pray for the betterment of humankind.

In the mid-1980s, just as Smith wrapped up his prayers, civil war erupted in Darjeeling as the ethnic Nepali population sought to secede from India. He slipped across the border to Nepal, married a Nepalese woman and raised a daughter, who is now 21 years old. Besides spending time with his family and passing a few unpleasant months in Orange County, he says, he’s led a very quiet life. He says he just wants to give his interview to the documentary crew making their movie about Buddhism, and then go back to Nepal.

I stop the car in front of the terminal where Smith is to board his flight. He shakes my hand and thanks me for my help. “Have a great life,” he says. “This may have been a short interview, but I am a simple man leading a simple life and don’t have much to give. I practice my religion day and night, all the time. I sleep very little, maybe three or four hours a day, and other than that, I sit and pray for the benefit of the world and the people who live in it and my own karma that follows me like a shadow in everything I do. What goes around comes around.”

To learn more about the Brotherhood, look for Nick Schou’s book, Orange Sunshine: The Brotherhood of Eternal Love and Its Quest to Spread Peace, Love and Acid to the World, published in March 2010 by Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press. [email protected]

“I feel basically the same,” he says. “Not any better, not any worse, just an ordinary day, coming and going, in one door and out the other.” We get in my car for the drive to the airport, and I hand my tape recorder to Smith so I can steer with two hands. He hands it back as he resigns himself to the challenge of buckling his seat belt again. “I really am not used to these safety belts,” he admits.

I try to ask Smith about the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, but he balks. “That’s all in the past,” he says as we leave the courthouse parking structure. “I live in the present.” Finally, Smith agrees to tell me what the Brotherhood tried to accomplish. “It was not about drugs or LSD or anything like that,” he says. “We wanted people to be happy and free and not like what society conditioned you to want to be. Basically, we loved everyone and wanted everyone to find love and happiness. We wanted to change the world in five years, but in five years, it changed us. It was an illusion.”

He still recalls the night Griggs died from his overdose of psilocybin. “He just took some, and as soon as he took it, he realized he had taken too much.” Griggs wandered back into his tepee and asked his wife not to take him to the hospital. “He knew he was going to leave his body that night,” Smith says. “He went into convulsions, and we put him in the car, and by the time he got to the hospital, they pronounced him dead.”

Happier memories include the time the Moody Blues showed up at the ranch to meet Leary, but they dropped so much acid they never got around to it, and how he and another Brotherhood member visited Mick Jagger and Keith Richards in their hotel room in Hollywood. “We smoked and hung out with them that evening and never saw them again,” he says. “They were aware of the Brotherhood but didn’t want to go to the ranch. Mick Jagger was nervous and thought we’d bring them trouble, and he was in enough trouble as it was with the different police departments all over the United States and Europe that wanted to bust him.”

As we reach the airport, Smith rushes to finish telling me how he spent the past 30 years of his life. He met his guru, Lama Kalu Rinpoche, at a Buddhist retreat in Palm Springs, about five years after becoming a fugitive. He followed Rinpoche from California to Maui to Darjeeling, India, where he spent the next 11 years living at Rinpoche’s monastery. Half that time, he lived in isolation, praying, “om mani padme hum” 100 million times. He befriended a quiet Norwegian, a fellow devotee of Rinpoche, who turned out to be extremely wealthy and who offered to sponsor Smith for the rest of his life if he continued to pray for the betterment of humankind.

In the mid-1980s, just as Smith wrapped up his prayers, civil war erupted in Darjeeling as the ethnic Nepali population sought to secede from India. He slipped across the border to Nepal, married a Nepalese woman and raised a daughter, who is now 21 years old. Besides spending time with his family and passing a few unpleasant months in Orange County, he says, he’s led a very quiet life. He says he just wants to give his interview to the documentary crew making their movie about Buddhism, and then go back to Nepal.

I stop the car in front of the terminal where Smith is to board his flight. He shakes my hand and thanks me for my help. “Have a great life,” he says. “This may have been a short interview, but I am a simple man leading a simple life and don’t have much to give. I practice my religion day and night, all the time. I sleep very little, maybe three or four hours a day, and other than that, I sit and pray for the benefit of the world and the people who live in it and my own karma that follows me like a shadow in everything I do. What goes around comes around.”

To learn more about the Brotherhood, look for Nick Schou’s book, Orange Sunshine: The Brotherhood of Eternal Love and Its Quest to Spread Peace, Love and Acid to the World, published in March 2010 by Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press. [email protected]

Fugitive member of 1960s LSD ring arrested

Brotherhood of Eternal Love member reportedly arrested returning from Nepal.

A fugitive member of a local group that distributed LSD worldwide has been arrested after nearly 40 years on the run.

Brenice Lee Smith, 64, was arrested at San Francisco International Airport on Saturday after flying in from Hong Kong, the OC Weekly reported.