Owsley

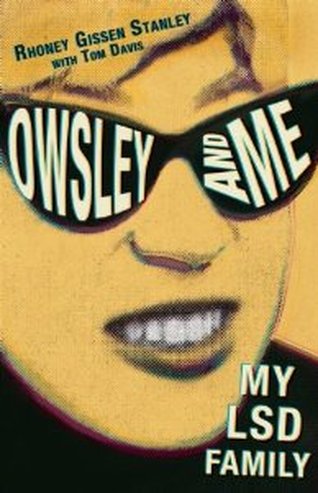

Owsley and Me

By Charles Perry (Rolling Stone, Nov. 25,1982)

In 1967, he was world-famous, as famous as you can get while refusing all contact with the news media. The Grateful Dead wrote a song about him. People who’d never met him talked about what a beautiful cat he was and wore buttons with his name on them.

It was a name to conjure with: Owsley. Owsley, the psychedelic guerrilla the narcs couldn’t catch, the heroic chemist whose LSD was the world standard of quality; Owsley, the Acid Millionaire. The newspapers called him “Mr. LSD.” Timothy Leary wrote of him as “the Alchemist.”Between 1965 and 1967 he made several million doses of LSD.

He was an astonishing phenomenon of the times, and nobody was more astonished than I was, because I’d known him long before he was a chemist. In fact, his career sort of started at my commune. It was while he was living with us in 1964 that he first took acid.

When I say “commune,” I’m calling it that in retrospect, because in 1964 nobody was using the word. It was just a crummy Berkeley rooming house where everybody turned out to be very simpatico and we started eating all our dinners together. But it actually did turn into a commune that fall, because I introduced everybody to LSD and it got too hard to keep track of who was chipping in on dinner and who wasn’t.

Dopers were a tiny minority in those days, even in college towns where drugs were becoming a sneaky fashion. Dope was hard to get – we were still buying grass by the half or even the quarter ounce, and psychedelics were in very short supply – so it was a paranoid,conspiratorial scene. Acid heads were nervous about walking around in public stoned, which didn’t make much sense, since LSD was still legal. Most dopers wasted a lot of energy worrying about whether their neighbors were suspicious of them, but we were fortunate to live in a house where everybody turned on.

Just how fortunate, we realized in January, 1964, when somebody moved out and all sorts of pensioners and bag ladies started answering the room for rent sign. Suddenly it looked as if our mellow scene was doomed, so when this guy in his late twenties checked out the room and started talking drugs within three minutes, we begged him to move in.

Forty-five minutes later, when he hadn’t stopped talking about drugs, we weren’t so sure he was cool. Not really tall, he had a sort of hulking manner anyhow, and a wary look, as if constantly planning an end run.We gathered that he was descended from an illustrious southern family –his full name, which he disliked and would legally shorten to “Owsley Stanley”in 1967, was Augustus Owsley Stanley III – and that he’d decided to go back to school after the breakup of his second marriage (and a subsequent legal scrape when he vengefully stole some credit cards from his ex-wife’s new boyfriend). But he had a more exotic perspective on himself. Sometimes he claimed to be a throwback to the carnivorous ape. Sometimes he boasted that, as a kid, he’d been at the same insane asylum as Ezra Pound.

Sometimes, in fact, our new roommate could be a little hard to take. His conversation was like a series of lectures:on the radar electronics he’d learned in the Air Force, the Russian grammar he’d studied when he was thinking of becoming a Russian Orthodox monk, the automotive technology he’d mastered while redesigning the engine of his MG.There were other obsessions too. When he moved into his room, he brought whole boxes full of weird stuff: ballet shoes, a complete beekeeper’s outfit, apainting in progress showing the arm of Christ on the cross, portrayed more or less from the Christ’s-eye viewpoint.

And he had all his theories to explain.Owsley was like the character in Naked Lunch who has “a theory on everything, like what kind of underwear is healthy.” He never ate dinner with us because he was an anti-vegetarian. He argued that since the human race is descended from carnivorous apes, our digestive system is designed for meat alone, and vegetables are slow poison. (He’d come to this theory after a vegetarian period, during which he’d started to lose his hair; it came back when he started staying away from veg.) Once, when he and I had smoked some hashish and developed a case of the blind munchies, all I had in myrefrigerator was apple pie, and he accused me of trying to poison him. “I haven’t had any plant food in my system for years,” he groused between mouthfuls. “My digestion will be fucked up for a month.” (When you are in perfect health, he once explained, you pass “one firm, odorless stool every ten days.”)

Soap bubbles on the roof top . . . events leading up to the powwow circle . . . eviction’s ugly face

The most surprising thing about Owsley was that this flagrant advocate for drugs had only been smoking grass for a couple of weeks when he moved in. He was making up for lost time, though. If you walked through the University of California campus with him, he’d be grabbing leaves and flowers and confiding in a paranoid hiss, “Horse chestnut leaves – they’ll get you high. Mullein leaves – get you high.” He had a huge stash of Heavenly Blue morning glory seeds, which contain an organic form of LSD along with some other organic stuff that gives you a million-year stomach ache. It ranked as a treasure trove, because the authorities had just gotten hip to the possibility of getting stoned on Heavenly Blues, and the seeds currently available in garden stores had all been denatured with something that made you even sicker. One of the first things Owsley did on moving into the commune was to order a rubber stamp reading “250 morning glory seeds . . . enough . . . $1,” and giving my phone number, because I was the only one in the commune with a phone. By the time he gleefully showed me thisboss robber stamp he’d had made, he’d already stamped that message on every bulletin board on the Cal campus. Nobody ever called, though.

We were all novice acid heads, just entering the phase where you go questing for that world of vast, timeless reality-energy-bliss that LSD suggests is . . . well, here and now, actually,only at the same time it’s just around some indescribable corner. So we were listening to sitar records and reading about Zen and blowing soap bubbles on the rooftop and in general keeping an eye peeled for indescribable corners.

Owsley was furiously trying every mind-affecting drug he could find mentioned in the chemical literature. He tried LSD along the line, of course. We didn’t happen to have any, so he scored some through a crazy little waif we knew as the Speed Freak Heiress. But though he was enthusiastic about LSD, his reaction was curiously mild in light of what was to come.

One day he asked me, “Charlie, what do you think about spikes?”

I had to think for a second to recall that a spike was a hypodermic needle. “Uh, they’re wrong,” I said. “If God had meant you to take that drug, he’d have given you an orifice for it.”

“Thanks,” said Owsley. “I’m glad I could talk with you about it. I was wondering because I saw some people shooting methedrine today.”

Uh-oh, I thought, he’s still hanging outwith the Speed Freak Heiress. Legend had it that her parents had once given her a mink coat in an attempt to reawaken her true sense of values, but she’d proceeded to wear it inside out so she could feel the fur against her skin.That was the squalid sort of life I associated with methedrine use, and I was glad I’d steered Owsley away from it.

The next day he had some more ideas about methedrine. He’d observed that meth freaks, whether out of greed or foolhardiness, seemed to make a point of keeping the needle in their veins until the last possible drop of geeze was punched in, even though that meant a repeated risk of embolism, that very dangerous situation of having a bubble of air in your bloodstream. Owsley’s theory was that speed freaks were probably giving themselves embolisms all the time – tiny ones, not big enough to cause heart failure, but big enough to make for little spots of brain damage.

And that’s why speed freaks had such spotty memories. That was why they were so freaky. Speed itself wasn’t at fault. No! Speed was . . . a tool!

So now, on top of all the other difficulties of having Owsley for a roommate, we had to put up with Owsley the amphetamine enthusiast, running around the commune at all hours, racing downstairs to ride his motorcycle at 3:30 a.m. Wherever you turned, there he’dbe, trying to cajole you into a taste of dimethyl amphetamine or his favorite cocktail of dimeth and methedrine.

It got so bad we held secret meetings toc onsider how to get rid of him. After all, we had a groovy little scene here.Lots of people wanted to room with us, particularly this math student we knew.Somehow Owsley got wind of the plans and came tearfully pleading with us to let him stay and making out the other guy to be a bigger speed dealer than himself(which turned out to be true). We were kind of ashamed of ourselves and dropped the plans.

But there was still a lot of disapprovalin the air, so to heal the philosophical breach with his friends, inside the commune and out, Owsley proposed that everybody give methedrine an honest trial. So one day a big powwow circle of 15 or 20 people gathered in his room and geezed up in a spirit of fair play.

It so happened that our landlord was a lonely Chinese bachelor who used to wander upstairs from time to time and make painful attempts at conversation. He chose this particular afternoon to stand in Owsley’s doorway and try one of his great conversational gambits –“Ah, nice weather we been having, ah?” was the one, I believe – on the powwow circle, which instantly turned into a huddle of teeth-grinding paranoids with eyes pingponging back and forth between the landlord and the damning pileof hypodermic needles in the middle of the floor.

After nobody would even agree that the weather had been nice, the landlord awkwardly excused himself and went back downstairs. Now the powwow circle was really paranoid, but Owsley was on top of things. “No,” he said, the light of inspiration in his eyes. “No, he’s not calling the police. He just realized we had something . . . beautiful here . .. and he was too shy to ask in! I’ll go offer to turn him on!” So we didn’t have to get rid of Owsley after all. The landlord evicted him on the spot.

By this time, Owsley had already droppedout of college and taken a job as a technician at KGO-TV in San Francisco. Hisconversational obsessions had narrowed to chemistry and particularly thesynthesis of alkaloids. He’d also picked up a new girlfriend, a better class ofchick in my opinion than he’d been getting with his motorcycle stud routine.She was a chemistry grad student named Melissa Cargill, a cute little honeybeewith tender intellectual eyes whom he’d met one day while doing someunauthorized messing around in the Cal chem labs. In three days flat he priedher away from a boyfriend who smoked a pipe and wore tweed jackets with leatherelbow patches and changed her mind about going on in grad school.

Bear Research Groupfounded . . . Owsley sues the state of California . . .

first LSD and freakout

I didn’t see Owsley for a couple of weeksafter he moved out. I graduated from Cal and moved out of the commune myself.When I next ran into him, he showed me some stationery he’d had printed up fora fictitious Bear Research Group, through which he was going to order chemicalsfrom the supply houses. It turned out I was part of his plan, because I’d justtaken a job tending rats in the Psychology Department’s animal labs. In casesome chemical company decided to inspect the Bear Research Group, where thisresearch on “the effect of methedrine on the cortisone metabolism of rats” wassupposedly going on, he wanted me to bring a dozen rat cages over to his placeand stand around in my white lab coat.

Frankly, I hoped he’d never test ourpalship by calling on that favor. I didn’t want anything to do with his currentscene, which consisted of hanging around with some truly sordid speed freaks,such as a guy who’d stand around all evening jerkily leafing through nudistmagazines – front to back, back to front, front to back again –muttering, “Process. It’s all process,” while the other speed freaks in the roomargued about who was alerting the police they imagined to be watching theirevery move by casting a shadow on the window shade.

I did drop by once in a while, though. Iliked Owsley. He could be overbearing, sure, but it wasn’t ill-inspired –he wasn’t a bully. There was always something disinterested and noblyintentioned in his relentless enthusiasms.

And his ideas were never boring. Forinstance: Einstein’s theories imply that gravity is a function of matter,right? And it has been proposed, on a principle of symmetry, that there is anantiuniverse parallel to our own, made up of antimatter, right? What wouldhappen if you transported some antimatter to this universe – andinstantly sent it back, of course, before there was a cataclysmic explosion– many times a second? Why, gravity would be annulled in the area! Whoknows what kind of machine could do this transporting of antimatter to ouruniverse and back? Who knows, indeed, what strange circuits are locked away inthe 90% of the human brain that is ordinarily unused?

And what could be the key to thisantigravity machine in our minds? Might it be something as simple as themandala-like pattern in a Persian rug . . . or flying carpet?

Owsley and Melissa were practicallyneighbors of mine at this time. I was living about three blocks from the “GreenFactory,” the sprawling green house at Virginia and McGee streets where he saidhe was making methedrine. One night a friend of Owsley’s who’d been crashingthere knocked at my door. On his way home from a folk music coffee house, he’dnoticed that something looked wrong about the Green Factory. He thought itmight have been busted.

We walked by the place. No sign of Billy,the guy who was supposed to be minding the place for Owsley while he was out oftown. We picked up another of Owsley’s friends and debated what to do. As theonly respectably employed member of the group, I was elected to call the policeand find out whether Billy had been arrested – a dimwit ordeal of thetime which involved asking the cops whether they’d arrested somebody whilestrenuously trying to give the impression that the very idea was unthinkable.Yes indeed, Billy was in jail, and the Green Factory had been raided.

We got hold of Melissa, who reflected forabout a minute and a half before pouring a pound or so of methedrine down aBerkeley storm drain with the cheerful resignation she could always summon in apinch. Owsley, however, would not prove resigned at all. When he got back totown, he had to face charges of operating a drug laboratory, but he was openlydefiant during the trial. And once he got the case thrown out – though itwas clearly a meth lab, couldn’t be described as anything else, in fact, thecops hadn’t found any actual methedrine there – he sued the state ofCalifornia for the return of his lab equipment. It was his, and he meant to useit.

Owsley was through fooling around, byGod. He and Melissa disappeared to Los Angeles for a few weeks to set up a newlab. It was not another meth lab. As a matter of fact, speed was becoming a matterof boredom and irritation with Owsley, and he was to become a vocal disparagerof amphetamines. No, when he came back to Berkeley in April, 1965, what heclaimed to have made was, to everybody’s surprise, LSD. I was skeptical. Butwhat the hell – in those days, we’d take any damn pill; once I droppedthree tabs I later found out were penicillin. Sure, I said, I’d try the“LSD”-dosed vitamin pill he handed me with one of his conspiratorial dopesmiles.

I casually dropped it the next Sunday,and godalmighty it was LSD. In about 40 minutes I was two-dimensional, fading intothe wall of the World Womb, which turned into the wall of an Egyptian tomb, andI was a painting of an ancient Egyptian on a tomb wall with hieroglyphicssprouting from my elbows and knees and disappearing down the wall too fast formy two-dimensional eyes to read. Now I had to face the basic question of theSixties: “OK, I’m high – is it fun?” On some trips, that could be a toughcall, but this time . . . no, it was clearly not fun. It was panicky. I walkeda mile and a half to find a friend from the old commune to talk me down.

The next day I told Owsley I’d turnedinto a wall painting. “Oh, that’s right,” he said. “You had one of those firstones. Hey, they were too heavy. You should have only taken half.”

Owsley’s Valley Forge .. . the Sun King of Berkeley . . . Owsley as Obi-Wan

There was already a lot of psychedelic orproto-psychedelic ferment in the San Francisco area. Folk musicians, who weresoon to prove so adept at writing music of, by and for acidheads, werefollowing Bob Dylan’s lead in abandoning the acoustic guitar for the electric.The first local folk-rock band made its debut at a kind of hippie nightclub inVirginia City, Nevada; Owsley’s acid was there on opening night. His LSD showedup in all the Bay Area coffeehouses and all of San Francisco’s hipneighborhoods, where the coolest dudes were walking around in three-pieceEdwardian suits from the secondhand stores, wearing rimless glasses withyellow-tinted lenses the size of quarters. They started having rock dances atthe Fillmore Auditorium and the Avalon Ballroom; Owsley was there, too. Thenovelist Ken Kesey started putting on public LSD parties called Acid Tests– LSD was still legal – and Owsley got himself instated as officialdonor of acid.

He started flying back to New York forstrategy sessions with Timothy Leary at Leary’s home in Millbrook. “Leary maybe the king in this little chess game,” he confided to me one day, “but whatnobody realizes is that I’m the rogue queen.” His personal style –maverick, purist, aggressive – started having an impact on thepsychedelic scene. LSD chemists had always been cautious, small-thinking mencontent to make a little acid and stay out of sight. Owsley, by contrast, had bigplans: to make the strongest LSD and to make it in unprecedented quantities. Bythe summer of 1965 he already had the raw materials to make 1.5 million doses.When his strong, consistent LSD flooded the market, it had the effect of amunitions factory opening at Valley Forge. Not only did it get a lot of peoplehigh, it encouraged the idea of big projects. It gave a big shot in the arm tothe boldness, the public outrageousness, that distinguished San Franciscoacidheads from the yoga-studying, indoor-tripping acids in other parts of thecountry.

Owsley had a personal campaign to turn onmusicians, whom he considered the key element of the psychedelic revolution. Hewas always backstage at the Fillmore and the Avalon trying to get them on hispsychedelic wavelength. I even heard about a time when he chatted with EarlScruggs, the bluegrass banjoist, using his best good-old-boy Southern manner,and then startled Scruggs by offering him LSD. On another occasion he returnedfrom New York crowing that he’d met “Bobby Dylan,” and that Dylan hadn’t gottenupset “until I mentioned acid.” Somebody who was there at the time later toldme how it went: He introduced himself by saying, “Hi, Bob, I’m Owsley. Wantsome acid?” and Dylan responded, “Who is this freak? Get him out of here!”

Characteristically, he got involved inrock and roll on the technical level. He gave $10,000 worth of electronicequipment to the Acid Test house band, which had just taken the name GratefulDead. It was an unheard-of thing to do at the time, treating that low-classrock music as if it deserved hi-fi speakers and amps. He also started recordingevery Grateful Dead performance using inscrutable techniques of his own, suchas mixing the sound with the aid of an oscilloscope.

For some months in 1965 and early 1966,Owsley was shuttling back and forth between his L.A. lab (where the GratefulDead lived for a while) and Berkeley. As for me, after my near freak-out onOwsley’s first acid I’d decided I didn’t want to live alone anymore, so I startedto room with some friends from the old Berkeley Way commune, including thechick who’d talked me down. When we moved out of her barn-like cottage onBerkeley Way, Owsley – who’d crashed there off and on himself –rented the cottage and settled there.

It was then that I started getting andidea of how much money he was making. Every afternoon, after he had arisen andtaken an hour-long shower, a regular retinue of petitioners would presentthemselves like serfs pleading for boons from the king. I can still see Owsleythere, listening warily but regally to their requests, enthroned in the nude ona huge fur-covered chair, drying his hair with the royal hairdryer.

One of his favorite pastimes was to takehis indigent old friends out to dinner – to places, of course, thatwouldn’t clutter up his plate with poisonous vegetables – and pay withthe roll of $20 and $100 bills he kept in his boot. His favorite restaurant wasOriginal Joe’s in San Francisco, where the steak was so good Owsley wasconvinced the chef had to be an acidhead. If Joe’s was closed, he’d takeeverybody to a Doggie Diner stand, order a double burger, extract the meatpatties and eat them. Then he’d crumple up the bun, drop it on the table with adull thud and announce to the world at large, “That’s what you’ve just put inyou stomachs.”

Or he’d take us to a fancy seafood placein Berkeley. Once he assembled such a weird group there – I remember ahuge black guy who ran with the Hell’s Angels and a hyper-intense guitarist whowas showing everybody how his fingertips were bleeding after eight hours ofsitar practice – that a lady came over to get our autographs for herdaughter, convinced that we had to be a rock band, she couldn’t think of ourname but her daughter would kill her if she didn’t get the autographs.

One time, it happened that I was the onlyone going along with Owsley to dinner. We couldn’t get into his regular seafoodplace, so we went to a marginally less fancy one up the block. When his orderof oysters came, though, Owsley declared them inedible --the “gizzards” hadbeen sliced into when they’d been opened. He lectured the waiter on the correctway to open an oyster and the general disregard for quality in our age. Thewaiter got the maitre d’, and they brought out the chef. The owner even cameout, and all four of them stood in a row to be lectured. The problem, Owsleytold them, was that they evidently didn’t have the right kind of oyster knife.“My business often takes me to New York,” he said (I momentarily blanched,since LSD had just become illegal), “and I’d be glad to get you a properknife.”

A new plate of oysters was brought out,but Owsley declared that the gizzards had again been cut. Again he returned it,repeating his lecture to the waiter, and a third plate was brought. Again thegizzards had been cut. When a fourth plate of oysters was sent to the table, hepronounced that only a few of the gizzards had been cut this time, and he wouldeat the oysters lest he be thought a troublesome customer. There was also aproblem with the pot of tea, something having to do with Owsley’s instructionthat it be served “Russian style.”

A year later, Owsley and I happened to gofor dinner again and wound up in the same place. “Mister Stanley,” said themaitre d’, his eyes narrowing as he smiled. “I remember you.” Owsley againordered oysters and again sent them back.

One thing about Owsley: He was neverafraid to be conspicuous. He had already adopted the turquoise-belt finery thatborder patrolmen would later call “the dealer look.” His theory was that copsdon’t register outrageousness, only the furtive attempt to be inconspicuous, soif you don’t give paranoia an inch, you’ll never get busted. Of course, ithelps to have nerves of steel, which Owsley certainly had. More than once I sawhim hypnotize a suspicious Highway Patrolman with his absolute confidence thatthe officer couldn’t possibly be looking for him. It was like the scenein Star Wars whereObi-Wan Kenobi bollixes an Imperial Stormtrooper. (“These aren’t the acidheadsyou want. They can go.”)

Manufacturing andmarketing practices of the Bear Research Group . . .

Troll House days

One day he told me, with justifiablepride, “My name is a household word in London and New York.” It was true. LSDwas all over the avant-garde circuit by late 1966, and Owsley’s acid was theundisputed standard of the industry. For a while, he ran around with two littlevials of crystalline LSD, one a pale straw color and the other, as he put it, “purefluffy white”; guess which LSD was made by the Sandoz chemical company andwhich came from the Bear Research Group. Early on, rival dealers were claimingto sell “genuine Owsley,” and Owsley took some interesting steps to deal withthis.

In the beginning, he had sold acid inpowdered form, ready for packing in gelatin capsules or, if you preferred,already capped. He also sold it in liquid form suitable for dosing sugar cubeswith an eyedropper. The liquid form was tinted pale blue, the exact shade of Wisklaundry detergent, so you could keep it in a carefully cleaned out Wisk bottle.If you were a prudent acid dealer, you always had a duffel bag full of dirtylaundry in your back seat to legitimize your Wisk bottle containing 4000 hitsof acid. (“Yes, officer, have you tried new, improved Wisk?”)

In 1966, Owsley stole a march on hiscompetition by buying a pill press and making the first illicitly manufacturedLSD tablets in history. That first press made irregular-looking pills that weresort of like the tubes of paper that build up in a paper punch (they werenicknamed “barrels”), but then he got a professional pill press that madepharmaceutical-style pills with a hairline crack so you could split them inhalf.

And finally, to keep the counterfeitersoff his trail for good, he began injecting each new batch with food coloring. Idistinctly remember pink, green, purple, orange and brown as well as white tabs(the famous White Lightnings that were handed out by the thousands at the HumanBe-In celebration in January, 1967). At one point, when he was on the outs withthe Grateful Dead, he started hanging around with a band called Blue Cheer andhelped publicize them by putting out a line of blue-tinted LSD.

Some writers have described LSD tabletswith Batman or Marvel Comics characters on him, but I never saw any, andfrankly, considering Owsley’s equipment, I can’t imagine how he could have madethem; I suspect some hippies were just having a little fun with the reporters.I would not put the idea of Spider-Man acid beyond Owsley, though. He washeavily into Marvel Comics and insisted that we call his hulking old red truck“the Dreaded Dormammu,” after the megalomaniacal villain of Dr. Strange comics.

I never worked in any of Owsley’s labs. Ididn’t have the time, because I was still holding down my animal caretakingjob, and working in an acid lab could take a week or ten days out of your life.LSD is an incredibly powerful substance. A single gram of the pure drug cansupply 4000 trips, and a little white speck you could barely see is enough tokill you. Once the LSD is synthesized, the most important job is to grind itexceedingly fine and then disperse it evenly in an inert medium such asdextrose. (Fortunately – or naturally, as it seemed to us -- LSDfluoresces under ultra-violet light, making even dispersal easy). After it’sdispersed, you can put it in capsules or make it into tablets.

The problem with all these jobs –grinding, dispersing, capping and tabbing – is that LSD would always geton your skin and into your lungs, and inevitably you’d be stoned. Nothingseemed to prevent it, not even scuba suits. Eventually, the people who workedin the labs decided not to bother with any precautions and just worked untilthey couldn’t concentrate any longer. Then they’d go wait out the eight or tenhours of the acid trip in a “cooling-off chamber,” get some sleep and go towork again. After a week or so of working on and off around the clock,half-gooned most of the time, the job would be done and Owsley would pay eachworker with a couple of hundred tabs of acid apiece.

He once outlined his distribution plansto me. He would have one principal dealer in every market, who would only sellthe acid to street dealers on the condition that they would resell it at nomore than $2 per hit. Eventually he planned to make LSD available at 25 cents ahit. I don’t know how this marketing plan worked out in practice, but at leastin rough outline it did seem to work that way in California and some East Coastcities. In Los Angeles, he had two dealers. One was for the Hollywood-BeverlyHills-Sunset Strip crowd. According to rumor, the other dealer – a blackguy who was living with a Unitarian minister’s daughter – was chosenbecause Owsley hoped he would get LSD into the black community. Actually, Idon’t think he ever dealt to anybody but Pasadena hippies, but he was a heck ofa nice guy.

I’ve heard it said that Owsley was amaster at calculating when the market could use more product and, conversely,that he would have had a lot more acid on the market if his manufacturing ordistribution had been better organized. For what it’s worth, Owsley has told methat he released a new batch of acid whenever he was curious about what theresult would be, as one might water a strange plant at different intervals tosee how it grows: “I would sit back and wait, and sure enough, ten days or twoweeks after a batch went out, there would be a whole rash of new developmentsin the Haight-Ashbury.”

He ascribed this reaction to the psychiceffect of LSD, which I don’t doubt, but there was an economic effect as well.Acid was now big business. Owsley demanded to be paid in $100 bills, nothinglarger or smaller. Sometimes when a new batch came out, there wouldn’t be a$100 bill to be found in any bank within 60 miles of San Francisco. When a newbatch arrived, the dealers would have lots of money, and since everybodyfigured the money would keep rolling in like this forever, they were throwingsome of their profit into shops, theaters, rock bands, publications and so on.Owsley himself contributed money or quantities of acid to Haight-Ashburyinstitutions such as the psychedelic newspaper The Oracle, the anarchist theatergroup known as the Diggers (who were famous for giving out free food in GoldenGate Park) and the free publishing company called the Communication Company,which placed its mimeographs at the disposal of anybody who wanted to printsomething and pass it out on Haight Street.

Sometime in the spring of 1967, Owsleymoved into an ultra-quaint cottage on Valley Street in Berkeley and filled itwith Persian rugs, hi-fi equipment, Indian fabrics, Tibetan wall hangings,pillows, hash pipes, musical instruments made by his personal guitar maker andall sorts of electronic toys, such as ultraviolet lamps and strobe lights. He’ddecided that Melissa’s totem animal was the owl, so he got her a pet owl thatwas always escaping from its cage. My supposed professional skills as an animalcaretaker were often called on to lure the bird back to its cage.

The Troll House, as some people calledit, was a regular stopover for the transcontinental psychedelic elite, fromRichard Alpert (later known as Baba Ram Dass) to out-of-town rock musicians.There was usually somebody trying to sleep on the pillow-strewn floor while the24-hour-a-day party lurched along. I dropped by every week or so to see thelatest wrinkle: ether-extracted THC, the advance copy of the Beatles’ Sgt.Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band or whatever.

A whole raft of newpsychedelics

and several trips upButterscotch Creek without a mind

It was the summer of 1967. I had quit myanimal-caretaking job to devote all my time to playing oboe with the TampaiGyentsen (Banner of the Faith) Tibetan Liturgical Orchestra. Owsley was changinghis personal style every couple of weeks: sailorish garb, the Prince Valiantand so on. LSD had been illegal since October, 1966, and the raw materials weregetting scarce. One day Owsley had showed me a letter from the Cyclo ChemicalCompany, which apologized that it wouldn’t be able to sell him any more rawlysergic acid. I remember laughing when I saw the name of the CEO who signedthe letter: Dr. Milan Panic. Curiously, this was the same Milan Panic who wouldreturn to his home country of Serbia in the 1990s and become its presidentunder prime minister Slobodan Milosevic.

But Owsley confided to me that the newlaws against LSD wouldn’t make any difference. “We’ve got a whole raft of new psychedelics,” hecrowed in his peculiarly cagey way, “and they’re gonna have to make each oneillegal separately. We’re gonna keep ’em running for years, and by that time,everybody will have been turned on!” Once everybody had been turned on, as allacidheads knew, history would be a whole new ball game.

These new drugs were chemically relatedto both methedrine and mescaline, the psychedelic found in peyote cactus. Thefirst one Owsley marketed was 2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine, which pickedup the nickname STP. I took an STP tab one Saturday and got so stoned that forthree days it made no difference whether my eyes were opened or closed, I wasseeing the same things. In fact, there was no difference between anything andanything else, except that sounds were like wood shavings curling infreeze-frame motion, while smells were more like subtly different levels ofvibration with smoke coming out of them.

I told Owsley that this stuff had turnedthe world into a river of butterscotch for three days running. “Oh, that’sright,” he said, in almost the same words I’d heard after guinea-pigging hisfirst LSD. “You had one of those pink ones. Hey, they were too heavy. Youshould have only taken half.”

STP flopped in the market. Not manypeople, it seemed, had three days at a time to spend in the butterscotchdimension, and there were a lot of freak-outs. Alas, it never got publicizedthat Owsley had a second purpose in mind for STP. In the Haight-Ashbury, bythen a teeming Calcutta of hippie dopers, methedrine was making a resurgence tothe detriment of the psychedelic mood. As a reformed speeder who had totallyturned against amphetamines, Owsley hoped STP would wean speeders toward a morespiritual trip. His theory was that if you took only 1/16 of a tab, you wouldget something like an amphetamine lift without the ugly speediness.

I tried it once when I needed to stayawake driving back from Los Angeles to Berkeley. Around Gorman, about an hourout of L.A., I started feeling funny and stopped off at a gas station. When Ilooked in the bathroom mirror, I saw that my right pupil was huge and my leftone was tiny; then the right pupil contracted and the left pupil dilated. Theywere alternating size like that every five or ten seconds.

Owsley falls at last . .. How to cope with prison . . . Of stereo & a vexed mix

Owsley had somehow managed to avoid thepolice since the Green Factory bust. They seemed to realize that here was noordinary dope chemist. In fact, when I got busted for grass with an old friendof his, I discovered that Owsley had the vice-mayor of Berkeley on retainer ashis attorney. In the late spring of 1967, Owsley had gotten busted whiledriving away from Leary’s place in Millbrook, but that was just a blunder-bust,a case of some New York highway cops stumbling onto a trunk full of dope, andthe charge didn’t stick.

But there was no denying that the narcswere on his trail. One day a bunch of us dropped by the workshop of Owsley’sfavorite glass blower, who was about to retire and literally sail around theworld on the money Owsley was paying him for some highly specialized labequipment, and the guy casually remarked, “Oh, Owsley, some federal agents wereby here the other day showing me photos of you and asking whether I’d ever seenthis person. They were rather good likenesses. You were in them too,” he added,nodding toward one of my roommates.

Finally, in December of 1967, with theHaight-Ashbury experiment collapsed into a monstrous stew of methedrine, heroinand strong-arm crime, the narcs finally got Owsley. The guy I’d gotten bustedfor grass with was living with a chick from the old commune who was dancingtopless in a San Francisco bar. Convention seemed to decree that a toplessdancer’s boyfriend should be a dealer; he got a job in Owsley’s lab and starteddealing the LSD he got paid in.

Unfortunately, he dealt to one of thenarcs who’d had Owsley under surveillance for the preceding 14 months. OnDecember 21, 1967, federal narcotics agents entered Owsley’s current lab andarrested him along with Melissa, this hapless dealer and two other friends of mine.Owsley was in a spitting rage. He was making all his drugs to FDA standards ofpurity, he protested; why weren’t the cops out arresting criminals? The San Francisco Chronicleran afine dramatic photo of the police leading Owsley away in handcuffs, defiant andresentful.

Everything had started to change. MyTibetan orchestra had fallen apart. The psychedelic revolution wasn’t panningout. I gravitated toward a pitifully small but energetic newspaper called RollingStone,which occupied an unused corner of a San Francisco printer’s loft. After acouple of months, I realized, to my surprise, that I was now a journalist.

Owsley was just beginning a five-yearlegal ordeal. While his LSD lab case was dragging through the courts, he gotbusted for marijuana a couple of times, once in New Orleans with the GratefulDead and once in Oakland when a landlord finked on him while he was sluggishlyvacating an apartment he’d been evicted from. Eventually, he was sent to prisonfor two years, serving part of his sentence at Terminal Island FederalCorrectional Institution in Los Angeles and part at Lompoc Federal Penitentiarynear Santa Barbara.

Lompoc isn’t so bad, as prisons go. It’sa white-collar jail; some of the Watergate conspirators served time there. Itreminded me of my high school campus, except that you couldn’t go home aftersixth period.

The first time I visited Owsley there, Ihad to wait almost to the end of the visitors’ hour. The guards weren’tsurprised; they were accustomed to inmate Stanley’s peculiarities. Finally hearrived, out of breath, with a belt buckle he’d started making for me when myname was announced over the loudspeakers. It was quite striking: a lion’s head(since I’m a Leo, I’m told) boldly composed of drops of molten brass.

Owsley not only had a jewelry lab inprison but all sorts of hi-fi and electronic equipment as well. The prisonauthorities were too damnably narrow-minded to provide such things, so he hadbeen obliged to have them all smuggled in – out on the visitors’ lawn forthe smaller things and under a pew in the chapel for big stuff like tape decks.The joke around Lompoc was that when Owsley was released, he’d have to leave ina Bekins van.

The second time I visited him, I actuallybrought him some little piece of electronic equipment he needed, I forget whatit was. But this time my visit was business. Rolling Stone wanted an interview withOwsley. Owsley, however, had always fought shy of reporters, and the proposalneeded a lot of discussing.

It seemed that while Owsley was in jail,Janis Joplin had died and a memorial album of her live performances had beenput together, including three tracks recorded by Owsley. He had been paid– no complaint on that score. But he had recorded Janis according to hisown theories about stereo (voices in one channel, instruments in the other),and Columbia Records had remixed the three tracks into conventional stereo forthe Joplin in Concert album. He wasn’t after more money, he emphasized. He simplywanted the record company to recall the albums and reissue them with hisoriginal mix of the three tracks. Columbia, however, was ignoring all hisletters.

So before Owsley could consider granting RollingStone aninterview, the paper would have to show its bona fides by planting a news itemsuggesting that “word was out on the street” that there was “something funny”about the stereo separation on some tracks of Joplin in Concert. We found a DJ who was willing to say there was something funny about anything that exists, and I puttogether an item that fit the bill. But after I had thus sullied my journalistic karma, Owsley reneged – he charged that we were only interested in his drug career and any interview would caricature him as a merechemist and has-been. Under the circumstances, he said, the best he could dofor us would be to write an essay on Marshall McLuhan. Which he would sign“Publius.”

Well, so much for that.

Some men are not born tobe components

It was toward the beginning of 1973 thatI next saw Owsley. He was out of jail, and I ran across him at the GratefulDead’s recording studio in San Francisco. There was a wild light in his eye.“Have you seen Joplin in Concert on the charts lately?” he asked. The album hadbeen on the best-seller charts for the better part of a year at that point.“It’s slipping,” he said significantly. “Sales are down.”

Uh-oh. He actually believed “word hadgotten out” about the funny stereo mix on three tracks of Joplin in Concert and people were swearingoff buying extra copies of it.

Owsley’s life had changed a lot since1967. He couldn’t afford his old flamboyance after the LSD factory bust; themoney wasn’t coming in any longer. In 1974 he told a federal judge he had lostmost of his savings in bad investments, to say nothing of legal fees, gifts andtoys and a solid diet of flank steak. Of course, there was no question ofreturning to his old business, not the way he has been watched since 1966. Hisonce-consuming interest in drugs had dwindled anyway, gone along withmotorcycles and beekeeping into the conflagration of burned bridges he leavesbehind him.

Even before going to prison, Owsley hadbeen working for the Grateful Dead, which is a huge extended family and alwaysmanages to find a place for everybody. For the most part, he worked their soundequipment and consulted with their hi-fi lab and recording studio – allperfectly logical, since the Dead’s hi-fi interests are something Owsleyinfected them with in the first place. He continued doing this sort of thingfor the Dead off and on after leaving prison, and he also worked with other SanFrancisco bands, even road-managing some tours.

He engineered a number of recordingsessions and even produced some albums. On rare occasion, he didultra-low-profile promo work for advanced studio sound equipment that met hisobsessive standards. It seems his approval has some weight in hi-fi circles.

The jewelry shop he put together in jailalso opened up a new range of activity for him. He became a sometime artist,turning out jewelry and small sculptures that combine a sort of blunt occulthumor with minimalist refinements of technique. It’s led him to new quests,such as the perfect bell metal, with the aim of making bells that would ringfor minutes on end when struck.

In the early ’80s, he had moved to arustic home up the coast from San Francisco. He was living a very private life,but apart from no longer being a drug manufacturer, he was living as he alwayshas. Surrounded by audio equipment, oriental rugs, occult books, African masksand welding tools, he continued to puzzle out the mysteries of the universe.He’d pace around the living room, drawing unexpected parallels: A biochemistrytext illustrates the same philosophical principle made in his latest sculpture,which in turn bears out his theory on the historical ramifications of thedevelopment of ultra hi-fi.

Strangely, he wouldn’t talk much aboutthe old days or what it all meant. He’s never been much of a reminiscer; he’salways engrossed in current projects. Sometimes he’d speak of what he’d done asa chemist as a humble attempt to “raise the level of bossness,” but he’dquickly lose interest in the subject.

Back in the ’60s, I always had theimpression that he was not committed to any particular theory of what was goingon but only riding this dragon to see where it led. Certainly he used toentertain theories about it that nobody else was willing to contemplate. Forinstance, it was a commonplace in 1967 that LSD was causing a sort ofaccelerated evolution of the human race, but only Owsley came up with thistwist: “What if LSD was not discovered by Albert Hoffman in the 1940s, butrevealed to him by beings from another planet who want us to evolve becausethey can use evolved intelligences as components in some immense, inconceivablemachine of theirs? And when we’ve taken enough LSD, when we’re ripe, they’ll .. . harvest us?”

Actually, I think about that theorysometimes when I come across somebody I haven’t seen since 1968 or so. Some ofthem look distinctly harvested.

Not Owsley, though. In fact, if I were togive advice to any alien intelligences, it would be this: “Nix. Don’t try toharvest this one. You don’t know what you’re in for.”

By Charles Perry (Rolling Stone, Nov. 25,1982)

In 1967, he was world-famous, as famous as you can get while refusing all contact with the news media. The Grateful Dead wrote a song about him. People who’d never met him talked about what a beautiful cat he was and wore buttons with his name on them.

It was a name to conjure with: Owsley. Owsley, the psychedelic guerrilla the narcs couldn’t catch, the heroic chemist whose LSD was the world standard of quality; Owsley, the Acid Millionaire. The newspapers called him “Mr. LSD.” Timothy Leary wrote of him as “the Alchemist.”Between 1965 and 1967 he made several million doses of LSD.

He was an astonishing phenomenon of the times, and nobody was more astonished than I was, because I’d known him long before he was a chemist. In fact, his career sort of started at my commune. It was while he was living with us in 1964 that he first took acid.

When I say “commune,” I’m calling it that in retrospect, because in 1964 nobody was using the word. It was just a crummy Berkeley rooming house where everybody turned out to be very simpatico and we started eating all our dinners together. But it actually did turn into a commune that fall, because I introduced everybody to LSD and it got too hard to keep track of who was chipping in on dinner and who wasn’t.

Dopers were a tiny minority in those days, even in college towns where drugs were becoming a sneaky fashion. Dope was hard to get – we were still buying grass by the half or even the quarter ounce, and psychedelics were in very short supply – so it was a paranoid,conspiratorial scene. Acid heads were nervous about walking around in public stoned, which didn’t make much sense, since LSD was still legal. Most dopers wasted a lot of energy worrying about whether their neighbors were suspicious of them, but we were fortunate to live in a house where everybody turned on.

Just how fortunate, we realized in January, 1964, when somebody moved out and all sorts of pensioners and bag ladies started answering the room for rent sign. Suddenly it looked as if our mellow scene was doomed, so when this guy in his late twenties checked out the room and started talking drugs within three minutes, we begged him to move in.

Forty-five minutes later, when he hadn’t stopped talking about drugs, we weren’t so sure he was cool. Not really tall, he had a sort of hulking manner anyhow, and a wary look, as if constantly planning an end run.We gathered that he was descended from an illustrious southern family –his full name, which he disliked and would legally shorten to “Owsley Stanley”in 1967, was Augustus Owsley Stanley III – and that he’d decided to go back to school after the breakup of his second marriage (and a subsequent legal scrape when he vengefully stole some credit cards from his ex-wife’s new boyfriend). But he had a more exotic perspective on himself. Sometimes he claimed to be a throwback to the carnivorous ape. Sometimes he boasted that, as a kid, he’d been at the same insane asylum as Ezra Pound.

Sometimes, in fact, our new roommate could be a little hard to take. His conversation was like a series of lectures:on the radar electronics he’d learned in the Air Force, the Russian grammar he’d studied when he was thinking of becoming a Russian Orthodox monk, the automotive technology he’d mastered while redesigning the engine of his MG.There were other obsessions too. When he moved into his room, he brought whole boxes full of weird stuff: ballet shoes, a complete beekeeper’s outfit, apainting in progress showing the arm of Christ on the cross, portrayed more or less from the Christ’s-eye viewpoint.

And he had all his theories to explain.Owsley was like the character in Naked Lunch who has “a theory on everything, like what kind of underwear is healthy.” He never ate dinner with us because he was an anti-vegetarian. He argued that since the human race is descended from carnivorous apes, our digestive system is designed for meat alone, and vegetables are slow poison. (He’d come to this theory after a vegetarian period, during which he’d started to lose his hair; it came back when he started staying away from veg.) Once, when he and I had smoked some hashish and developed a case of the blind munchies, all I had in myrefrigerator was apple pie, and he accused me of trying to poison him. “I haven’t had any plant food in my system for years,” he groused between mouthfuls. “My digestion will be fucked up for a month.” (When you are in perfect health, he once explained, you pass “one firm, odorless stool every ten days.”)

Soap bubbles on the roof top . . . events leading up to the powwow circle . . . eviction’s ugly face

The most surprising thing about Owsley was that this flagrant advocate for drugs had only been smoking grass for a couple of weeks when he moved in. He was making up for lost time, though. If you walked through the University of California campus with him, he’d be grabbing leaves and flowers and confiding in a paranoid hiss, “Horse chestnut leaves – they’ll get you high. Mullein leaves – get you high.” He had a huge stash of Heavenly Blue morning glory seeds, which contain an organic form of LSD along with some other organic stuff that gives you a million-year stomach ache. It ranked as a treasure trove, because the authorities had just gotten hip to the possibility of getting stoned on Heavenly Blues, and the seeds currently available in garden stores had all been denatured with something that made you even sicker. One of the first things Owsley did on moving into the commune was to order a rubber stamp reading “250 morning glory seeds . . . enough . . . $1,” and giving my phone number, because I was the only one in the commune with a phone. By the time he gleefully showed me thisboss robber stamp he’d had made, he’d already stamped that message on every bulletin board on the Cal campus. Nobody ever called, though.

We were all novice acid heads, just entering the phase where you go questing for that world of vast, timeless reality-energy-bliss that LSD suggests is . . . well, here and now, actually,only at the same time it’s just around some indescribable corner. So we were listening to sitar records and reading about Zen and blowing soap bubbles on the rooftop and in general keeping an eye peeled for indescribable corners.

Owsley was furiously trying every mind-affecting drug he could find mentioned in the chemical literature. He tried LSD along the line, of course. We didn’t happen to have any, so he scored some through a crazy little waif we knew as the Speed Freak Heiress. But though he was enthusiastic about LSD, his reaction was curiously mild in light of what was to come.

One day he asked me, “Charlie, what do you think about spikes?”

I had to think for a second to recall that a spike was a hypodermic needle. “Uh, they’re wrong,” I said. “If God had meant you to take that drug, he’d have given you an orifice for it.”

“Thanks,” said Owsley. “I’m glad I could talk with you about it. I was wondering because I saw some people shooting methedrine today.”

Uh-oh, I thought, he’s still hanging outwith the Speed Freak Heiress. Legend had it that her parents had once given her a mink coat in an attempt to reawaken her true sense of values, but she’d proceeded to wear it inside out so she could feel the fur against her skin.That was the squalid sort of life I associated with methedrine use, and I was glad I’d steered Owsley away from it.

The next day he had some more ideas about methedrine. He’d observed that meth freaks, whether out of greed or foolhardiness, seemed to make a point of keeping the needle in their veins until the last possible drop of geeze was punched in, even though that meant a repeated risk of embolism, that very dangerous situation of having a bubble of air in your bloodstream. Owsley’s theory was that speed freaks were probably giving themselves embolisms all the time – tiny ones, not big enough to cause heart failure, but big enough to make for little spots of brain damage.

And that’s why speed freaks had such spotty memories. That was why they were so freaky. Speed itself wasn’t at fault. No! Speed was . . . a tool!

So now, on top of all the other difficulties of having Owsley for a roommate, we had to put up with Owsley the amphetamine enthusiast, running around the commune at all hours, racing downstairs to ride his motorcycle at 3:30 a.m. Wherever you turned, there he’dbe, trying to cajole you into a taste of dimethyl amphetamine or his favorite cocktail of dimeth and methedrine.

It got so bad we held secret meetings toc onsider how to get rid of him. After all, we had a groovy little scene here.Lots of people wanted to room with us, particularly this math student we knew.Somehow Owsley got wind of the plans and came tearfully pleading with us to let him stay and making out the other guy to be a bigger speed dealer than himself(which turned out to be true). We were kind of ashamed of ourselves and dropped the plans.

But there was still a lot of disapprovalin the air, so to heal the philosophical breach with his friends, inside the commune and out, Owsley proposed that everybody give methedrine an honest trial. So one day a big powwow circle of 15 or 20 people gathered in his room and geezed up in a spirit of fair play.

It so happened that our landlord was a lonely Chinese bachelor who used to wander upstairs from time to time and make painful attempts at conversation. He chose this particular afternoon to stand in Owsley’s doorway and try one of his great conversational gambits –“Ah, nice weather we been having, ah?” was the one, I believe – on the powwow circle, which instantly turned into a huddle of teeth-grinding paranoids with eyes pingponging back and forth between the landlord and the damning pileof hypodermic needles in the middle of the floor.

After nobody would even agree that the weather had been nice, the landlord awkwardly excused himself and went back downstairs. Now the powwow circle was really paranoid, but Owsley was on top of things. “No,” he said, the light of inspiration in his eyes. “No, he’s not calling the police. He just realized we had something . . . beautiful here . .. and he was too shy to ask in! I’ll go offer to turn him on!” So we didn’t have to get rid of Owsley after all. The landlord evicted him on the spot.

By this time, Owsley had already droppedout of college and taken a job as a technician at KGO-TV in San Francisco. Hisconversational obsessions had narrowed to chemistry and particularly thesynthesis of alkaloids. He’d also picked up a new girlfriend, a better class ofchick in my opinion than he’d been getting with his motorcycle stud routine.She was a chemistry grad student named Melissa Cargill, a cute little honeybeewith tender intellectual eyes whom he’d met one day while doing someunauthorized messing around in the Cal chem labs. In three days flat he priedher away from a boyfriend who smoked a pipe and wore tweed jackets with leatherelbow patches and changed her mind about going on in grad school.

Bear Research Groupfounded . . . Owsley sues the state of California . . .

first LSD and freakout

I didn’t see Owsley for a couple of weeksafter he moved out. I graduated from Cal and moved out of the commune myself.When I next ran into him, he showed me some stationery he’d had printed up fora fictitious Bear Research Group, through which he was going to order chemicalsfrom the supply houses. It turned out I was part of his plan, because I’d justtaken a job tending rats in the Psychology Department’s animal labs. In casesome chemical company decided to inspect the Bear Research Group, where thisresearch on “the effect of methedrine on the cortisone metabolism of rats” wassupposedly going on, he wanted me to bring a dozen rat cages over to his placeand stand around in my white lab coat.

Frankly, I hoped he’d never test ourpalship by calling on that favor. I didn’t want anything to do with his currentscene, which consisted of hanging around with some truly sordid speed freaks,such as a guy who’d stand around all evening jerkily leafing through nudistmagazines – front to back, back to front, front to back again –muttering, “Process. It’s all process,” while the other speed freaks in the roomargued about who was alerting the police they imagined to be watching theirevery move by casting a shadow on the window shade.

I did drop by once in a while, though. Iliked Owsley. He could be overbearing, sure, but it wasn’t ill-inspired –he wasn’t a bully. There was always something disinterested and noblyintentioned in his relentless enthusiasms.

And his ideas were never boring. Forinstance: Einstein’s theories imply that gravity is a function of matter,right? And it has been proposed, on a principle of symmetry, that there is anantiuniverse parallel to our own, made up of antimatter, right? What wouldhappen if you transported some antimatter to this universe – andinstantly sent it back, of course, before there was a cataclysmic explosion– many times a second? Why, gravity would be annulled in the area! Whoknows what kind of machine could do this transporting of antimatter to ouruniverse and back? Who knows, indeed, what strange circuits are locked away inthe 90% of the human brain that is ordinarily unused?

And what could be the key to thisantigravity machine in our minds? Might it be something as simple as themandala-like pattern in a Persian rug . . . or flying carpet?

Owsley and Melissa were practicallyneighbors of mine at this time. I was living about three blocks from the “GreenFactory,” the sprawling green house at Virginia and McGee streets where he saidhe was making methedrine. One night a friend of Owsley’s who’d been crashingthere knocked at my door. On his way home from a folk music coffee house, he’dnoticed that something looked wrong about the Green Factory. He thought itmight have been busted.

We walked by the place. No sign of Billy,the guy who was supposed to be minding the place for Owsley while he was out oftown. We picked up another of Owsley’s friends and debated what to do. As theonly respectably employed member of the group, I was elected to call the policeand find out whether Billy had been arrested – a dimwit ordeal of thetime which involved asking the cops whether they’d arrested somebody whilestrenuously trying to give the impression that the very idea was unthinkable.Yes indeed, Billy was in jail, and the Green Factory had been raided.

We got hold of Melissa, who reflected forabout a minute and a half before pouring a pound or so of methedrine down aBerkeley storm drain with the cheerful resignation she could always summon in apinch. Owsley, however, would not prove resigned at all. When he got back totown, he had to face charges of operating a drug laboratory, but he was openlydefiant during the trial. And once he got the case thrown out – though itwas clearly a meth lab, couldn’t be described as anything else, in fact, thecops hadn’t found any actual methedrine there – he sued the state ofCalifornia for the return of his lab equipment. It was his, and he meant to useit.

Owsley was through fooling around, byGod. He and Melissa disappeared to Los Angeles for a few weeks to set up a newlab. It was not another meth lab. As a matter of fact, speed was becoming a matterof boredom and irritation with Owsley, and he was to become a vocal disparagerof amphetamines. No, when he came back to Berkeley in April, 1965, what heclaimed to have made was, to everybody’s surprise, LSD. I was skeptical. Butwhat the hell – in those days, we’d take any damn pill; once I droppedthree tabs I later found out were penicillin. Sure, I said, I’d try the“LSD”-dosed vitamin pill he handed me with one of his conspiratorial dopesmiles.

I casually dropped it the next Sunday,and godalmighty it was LSD. In about 40 minutes I was two-dimensional, fading intothe wall of the World Womb, which turned into the wall of an Egyptian tomb, andI was a painting of an ancient Egyptian on a tomb wall with hieroglyphicssprouting from my elbows and knees and disappearing down the wall too fast formy two-dimensional eyes to read. Now I had to face the basic question of theSixties: “OK, I’m high – is it fun?” On some trips, that could be a toughcall, but this time . . . no, it was clearly not fun. It was panicky. I walkeda mile and a half to find a friend from the old commune to talk me down.

The next day I told Owsley I’d turnedinto a wall painting. “Oh, that’s right,” he said. “You had one of those firstones. Hey, they were too heavy. You should have only taken half.”

Owsley’s Valley Forge .. . the Sun King of Berkeley . . . Owsley as Obi-Wan

There was already a lot of psychedelic orproto-psychedelic ferment in the San Francisco area. Folk musicians, who weresoon to prove so adept at writing music of, by and for acidheads, werefollowing Bob Dylan’s lead in abandoning the acoustic guitar for the electric.The first local folk-rock band made its debut at a kind of hippie nightclub inVirginia City, Nevada; Owsley’s acid was there on opening night. His LSD showedup in all the Bay Area coffeehouses and all of San Francisco’s hipneighborhoods, where the coolest dudes were walking around in three-pieceEdwardian suits from the secondhand stores, wearing rimless glasses withyellow-tinted lenses the size of quarters. They started having rock dances atthe Fillmore Auditorium and the Avalon Ballroom; Owsley was there, too. Thenovelist Ken Kesey started putting on public LSD parties called Acid Tests– LSD was still legal – and Owsley got himself instated as officialdonor of acid.

He started flying back to New York forstrategy sessions with Timothy Leary at Leary’s home in Millbrook. “Leary maybe the king in this little chess game,” he confided to me one day, “but whatnobody realizes is that I’m the rogue queen.” His personal style –maverick, purist, aggressive – started having an impact on thepsychedelic scene. LSD chemists had always been cautious, small-thinking mencontent to make a little acid and stay out of sight. Owsley, by contrast, had bigplans: to make the strongest LSD and to make it in unprecedented quantities. Bythe summer of 1965 he already had the raw materials to make 1.5 million doses.When his strong, consistent LSD flooded the market, it had the effect of amunitions factory opening at Valley Forge. Not only did it get a lot of peoplehigh, it encouraged the idea of big projects. It gave a big shot in the arm tothe boldness, the public outrageousness, that distinguished San Franciscoacidheads from the yoga-studying, indoor-tripping acids in other parts of thecountry.

Owsley had a personal campaign to turn onmusicians, whom he considered the key element of the psychedelic revolution. Hewas always backstage at the Fillmore and the Avalon trying to get them on hispsychedelic wavelength. I even heard about a time when he chatted with EarlScruggs, the bluegrass banjoist, using his best good-old-boy Southern manner,and then startled Scruggs by offering him LSD. On another occasion he returnedfrom New York crowing that he’d met “Bobby Dylan,” and that Dylan hadn’t gottenupset “until I mentioned acid.” Somebody who was there at the time later toldme how it went: He introduced himself by saying, “Hi, Bob, I’m Owsley. Wantsome acid?” and Dylan responded, “Who is this freak? Get him out of here!”

Characteristically, he got involved inrock and roll on the technical level. He gave $10,000 worth of electronicequipment to the Acid Test house band, which had just taken the name GratefulDead. It was an unheard-of thing to do at the time, treating that low-classrock music as if it deserved hi-fi speakers and amps. He also started recordingevery Grateful Dead performance using inscrutable techniques of his own, suchas mixing the sound with the aid of an oscilloscope.

For some months in 1965 and early 1966,Owsley was shuttling back and forth between his L.A. lab (where the GratefulDead lived for a while) and Berkeley. As for me, after my near freak-out onOwsley’s first acid I’d decided I didn’t want to live alone anymore, so I startedto room with some friends from the old Berkeley Way commune, including thechick who’d talked me down. When we moved out of her barn-like cottage onBerkeley Way, Owsley – who’d crashed there off and on himself –rented the cottage and settled there.

It was then that I started getting andidea of how much money he was making. Every afternoon, after he had arisen andtaken an hour-long shower, a regular retinue of petitioners would presentthemselves like serfs pleading for boons from the king. I can still see Owsleythere, listening warily but regally to their requests, enthroned in the nude ona huge fur-covered chair, drying his hair with the royal hairdryer.

One of his favorite pastimes was to takehis indigent old friends out to dinner – to places, of course, thatwouldn’t clutter up his plate with poisonous vegetables – and pay withthe roll of $20 and $100 bills he kept in his boot. His favorite restaurant wasOriginal Joe’s in San Francisco, where the steak was so good Owsley wasconvinced the chef had to be an acidhead. If Joe’s was closed, he’d takeeverybody to a Doggie Diner stand, order a double burger, extract the meatpatties and eat them. Then he’d crumple up the bun, drop it on the table with adull thud and announce to the world at large, “That’s what you’ve just put inyou stomachs.”

Or he’d take us to a fancy seafood placein Berkeley. Once he assembled such a weird group there – I remember ahuge black guy who ran with the Hell’s Angels and a hyper-intense guitarist whowas showing everybody how his fingertips were bleeding after eight hours ofsitar practice – that a lady came over to get our autographs for herdaughter, convinced that we had to be a rock band, she couldn’t think of ourname but her daughter would kill her if she didn’t get the autographs.

One time, it happened that I was the onlyone going along with Owsley to dinner. We couldn’t get into his regular seafoodplace, so we went to a marginally less fancy one up the block. When his orderof oysters came, though, Owsley declared them inedible --the “gizzards” hadbeen sliced into when they’d been opened. He lectured the waiter on the correctway to open an oyster and the general disregard for quality in our age. Thewaiter got the maitre d’, and they brought out the chef. The owner even cameout, and all four of them stood in a row to be lectured. The problem, Owsleytold them, was that they evidently didn’t have the right kind of oyster knife.“My business often takes me to New York,” he said (I momentarily blanched,since LSD had just become illegal), “and I’d be glad to get you a properknife.”

A new plate of oysters was brought out,but Owsley declared that the gizzards had again been cut. Again he returned it,repeating his lecture to the waiter, and a third plate was brought. Again thegizzards had been cut. When a fourth plate of oysters was sent to the table, hepronounced that only a few of the gizzards had been cut this time, and he wouldeat the oysters lest he be thought a troublesome customer. There was also aproblem with the pot of tea, something having to do with Owsley’s instructionthat it be served “Russian style.”

A year later, Owsley and I happened to gofor dinner again and wound up in the same place. “Mister Stanley,” said themaitre d’, his eyes narrowing as he smiled. “I remember you.” Owsley againordered oysters and again sent them back.

One thing about Owsley: He was neverafraid to be conspicuous. He had already adopted the turquoise-belt finery thatborder patrolmen would later call “the dealer look.” His theory was that copsdon’t register outrageousness, only the furtive attempt to be inconspicuous, soif you don’t give paranoia an inch, you’ll never get busted. Of course, ithelps to have nerves of steel, which Owsley certainly had. More than once I sawhim hypnotize a suspicious Highway Patrolman with his absolute confidence thatthe officer couldn’t possibly be looking for him. It was like the scenein Star Wars whereObi-Wan Kenobi bollixes an Imperial Stormtrooper. (“These aren’t the acidheadsyou want. They can go.”)

Manufacturing andmarketing practices of the Bear Research Group . . .

Troll House days

One day he told me, with justifiablepride, “My name is a household word in London and New York.” It was true. LSDwas all over the avant-garde circuit by late 1966, and Owsley’s acid was theundisputed standard of the industry. For a while, he ran around with two littlevials of crystalline LSD, one a pale straw color and the other, as he put it, “purefluffy white”; guess which LSD was made by the Sandoz chemical company andwhich came from the Bear Research Group. Early on, rival dealers were claimingto sell “genuine Owsley,” and Owsley took some interesting steps to deal withthis.

In the beginning, he had sold acid inpowdered form, ready for packing in gelatin capsules or, if you preferred,already capped. He also sold it in liquid form suitable for dosing sugar cubeswith an eyedropper. The liquid form was tinted pale blue, the exact shade of Wisklaundry detergent, so you could keep it in a carefully cleaned out Wisk bottle.If you were a prudent acid dealer, you always had a duffel bag full of dirtylaundry in your back seat to legitimize your Wisk bottle containing 4000 hitsof acid. (“Yes, officer, have you tried new, improved Wisk?”)

In 1966, Owsley stole a march on hiscompetition by buying a pill press and making the first illicitly manufacturedLSD tablets in history. That first press made irregular-looking pills that weresort of like the tubes of paper that build up in a paper punch (they werenicknamed “barrels”), but then he got a professional pill press that madepharmaceutical-style pills with a hairline crack so you could split them inhalf.

And finally, to keep the counterfeitersoff his trail for good, he began injecting each new batch with food coloring. Idistinctly remember pink, green, purple, orange and brown as well as white tabs(the famous White Lightnings that were handed out by the thousands at the HumanBe-In celebration in January, 1967). At one point, when he was on the outs withthe Grateful Dead, he started hanging around with a band called Blue Cheer andhelped publicize them by putting out a line of blue-tinted LSD.

Some writers have described LSD tabletswith Batman or Marvel Comics characters on him, but I never saw any, andfrankly, considering Owsley’s equipment, I can’t imagine how he could have madethem; I suspect some hippies were just having a little fun with the reporters.I would not put the idea of Spider-Man acid beyond Owsley, though. He washeavily into Marvel Comics and insisted that we call his hulking old red truck“the Dreaded Dormammu,” after the megalomaniacal villain of Dr. Strange comics.

I never worked in any of Owsley’s labs. Ididn’t have the time, because I was still holding down my animal caretakingjob, and working in an acid lab could take a week or ten days out of your life.LSD is an incredibly powerful substance. A single gram of the pure drug cansupply 4000 trips, and a little white speck you could barely see is enough tokill you. Once the LSD is synthesized, the most important job is to grind itexceedingly fine and then disperse it evenly in an inert medium such asdextrose. (Fortunately – or naturally, as it seemed to us -- LSDfluoresces under ultra-violet light, making even dispersal easy). After it’sdispersed, you can put it in capsules or make it into tablets.

The problem with all these jobs –grinding, dispersing, capping and tabbing – is that LSD would always geton your skin and into your lungs, and inevitably you’d be stoned. Nothingseemed to prevent it, not even scuba suits. Eventually, the people who workedin the labs decided not to bother with any precautions and just worked untilthey couldn’t concentrate any longer. Then they’d go wait out the eight or tenhours of the acid trip in a “cooling-off chamber,” get some sleep and go towork again. After a week or so of working on and off around the clock,half-gooned most of the time, the job would be done and Owsley would pay eachworker with a couple of hundred tabs of acid apiece.

He once outlined his distribution plansto me. He would have one principal dealer in every market, who would only sellthe acid to street dealers on the condition that they would resell it at nomore than $2 per hit. Eventually he planned to make LSD available at 25 cents ahit. I don’t know how this marketing plan worked out in practice, but at leastin rough outline it did seem to work that way in California and some East Coastcities. In Los Angeles, he had two dealers. One was for the Hollywood-BeverlyHills-Sunset Strip crowd. According to rumor, the other dealer – a blackguy who was living with a Unitarian minister’s daughter – was chosenbecause Owsley hoped he would get LSD into the black community. Actually, Idon’t think he ever dealt to anybody but Pasadena hippies, but he was a heck ofa nice guy.

I’ve heard it said that Owsley was amaster at calculating when the market could use more product and, conversely,that he would have had a lot more acid on the market if his manufacturing ordistribution had been better organized. For what it’s worth, Owsley has told methat he released a new batch of acid whenever he was curious about what theresult would be, as one might water a strange plant at different intervals tosee how it grows: “I would sit back and wait, and sure enough, ten days or twoweeks after a batch went out, there would be a whole rash of new developmentsin the Haight-Ashbury.”

He ascribed this reaction to the psychiceffect of LSD, which I don’t doubt, but there was an economic effect as well.Acid was now big business. Owsley demanded to be paid in $100 bills, nothinglarger or smaller. Sometimes when a new batch came out, there wouldn’t be a$100 bill to be found in any bank within 60 miles of San Francisco. When a newbatch arrived, the dealers would have lots of money, and since everybodyfigured the money would keep rolling in like this forever, they were throwingsome of their profit into shops, theaters, rock bands, publications and so on.Owsley himself contributed money or quantities of acid to Haight-Ashburyinstitutions such as the psychedelic newspaper The Oracle, the anarchist theatergroup known as the Diggers (who were famous for giving out free food in GoldenGate Park) and the free publishing company called the Communication Company,which placed its mimeographs at the disposal of anybody who wanted to printsomething and pass it out on Haight Street.

Sometime in the spring of 1967, Owsleymoved into an ultra-quaint cottage on Valley Street in Berkeley and filled itwith Persian rugs, hi-fi equipment, Indian fabrics, Tibetan wall hangings,pillows, hash pipes, musical instruments made by his personal guitar maker andall sorts of electronic toys, such as ultraviolet lamps and strobe lights. He’ddecided that Melissa’s totem animal was the owl, so he got her a pet owl thatwas always escaping from its cage. My supposed professional skills as an animalcaretaker were often called on to lure the bird back to its cage.

The Troll House, as some people calledit, was a regular stopover for the transcontinental psychedelic elite, fromRichard Alpert (later known as Baba Ram Dass) to out-of-town rock musicians.There was usually somebody trying to sleep on the pillow-strewn floor while the24-hour-a-day party lurched along. I dropped by every week or so to see thelatest wrinkle: ether-extracted THC, the advance copy of the Beatles’ Sgt.Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band or whatever.

A whole raft of newpsychedelics

and several trips upButterscotch Creek without a mind

It was the summer of 1967. I had quit myanimal-caretaking job to devote all my time to playing oboe with the TampaiGyentsen (Banner of the Faith) Tibetan Liturgical Orchestra. Owsley was changinghis personal style every couple of weeks: sailorish garb, the Prince Valiantand so on. LSD had been illegal since October, 1966, and the raw materials weregetting scarce. One day Owsley had showed me a letter from the Cyclo ChemicalCompany, which apologized that it wouldn’t be able to sell him any more rawlysergic acid. I remember laughing when I saw the name of the CEO who signedthe letter: Dr. Milan Panic. Curiously, this was the same Milan Panic who wouldreturn to his home country of Serbia in the 1990s and become its presidentunder prime minister Slobodan Milosevic.

But Owsley confided to me that the newlaws against LSD wouldn’t make any difference. “We’ve got a whole raft of new psychedelics,” hecrowed in his peculiarly cagey way, “and they’re gonna have to make each oneillegal separately. We’re gonna keep ’em running for years, and by that time,everybody will have been turned on!” Once everybody had been turned on, as allacidheads knew, history would be a whole new ball game.

These new drugs were chemically relatedto both methedrine and mescaline, the psychedelic found in peyote cactus. Thefirst one Owsley marketed was 2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine, which pickedup the nickname STP. I took an STP tab one Saturday and got so stoned that forthree days it made no difference whether my eyes were opened or closed, I wasseeing the same things. In fact, there was no difference between anything andanything else, except that sounds were like wood shavings curling infreeze-frame motion, while smells were more like subtly different levels ofvibration with smoke coming out of them.

I told Owsley that this stuff had turnedthe world into a river of butterscotch for three days running. “Oh, that’sright,” he said, in almost the same words I’d heard after guinea-pigging hisfirst LSD. “You had one of those pink ones. Hey, they were too heavy. Youshould have only taken half.”