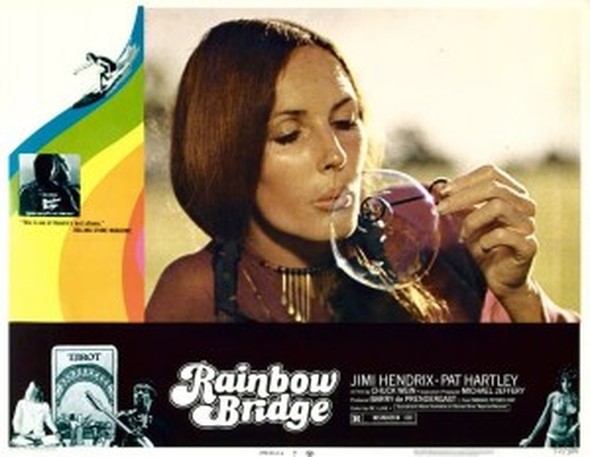

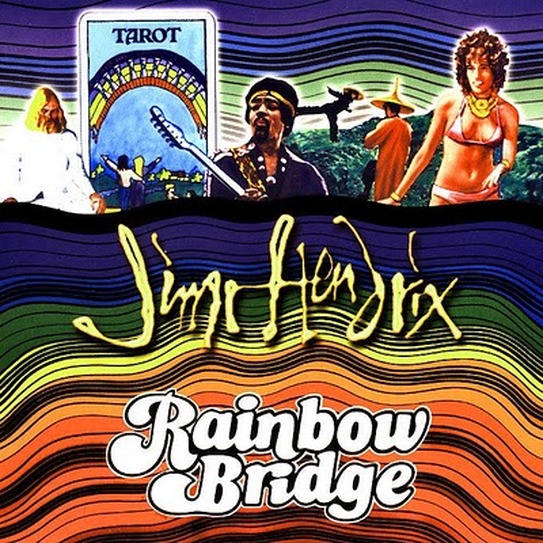

Rainbow Bridge

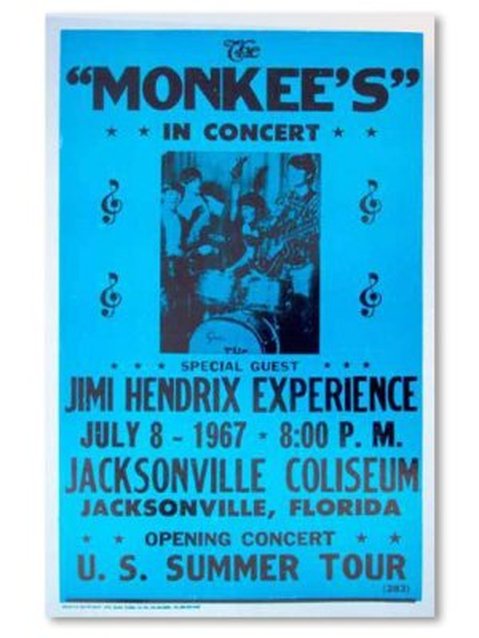

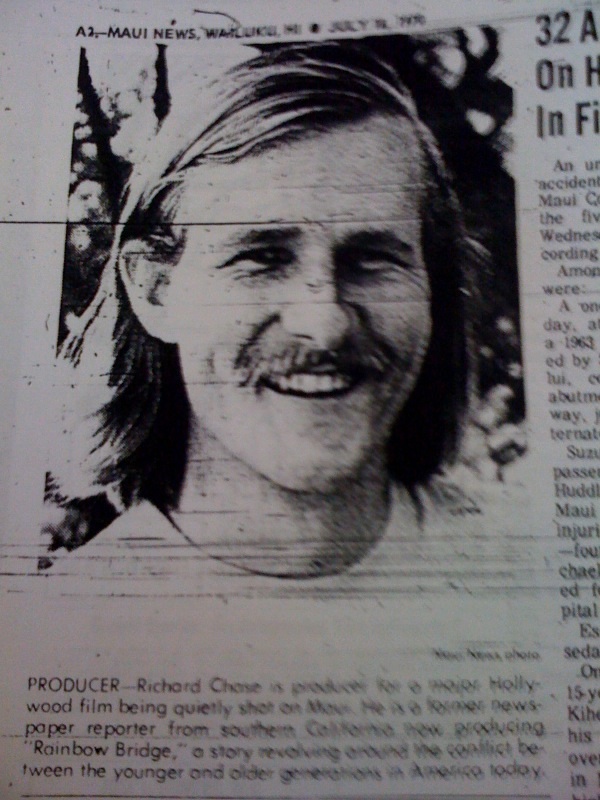

A Film that Anticipated Reality TV Style

1972 Film

starring Jimi Hendrix

This new and revealing programme provides an incredibly detailed account of how Jimi Hendrix, a legendary guitarist touched by genius, lived his life in the high powered world of 60's Rock 'n Roll. Through rare and exclusive interviews plus explosive performance footage, including the track Hey Joe, Sunshine of your Love and Purple Haze, Feedback explores the inside track of this phenomenal talent.

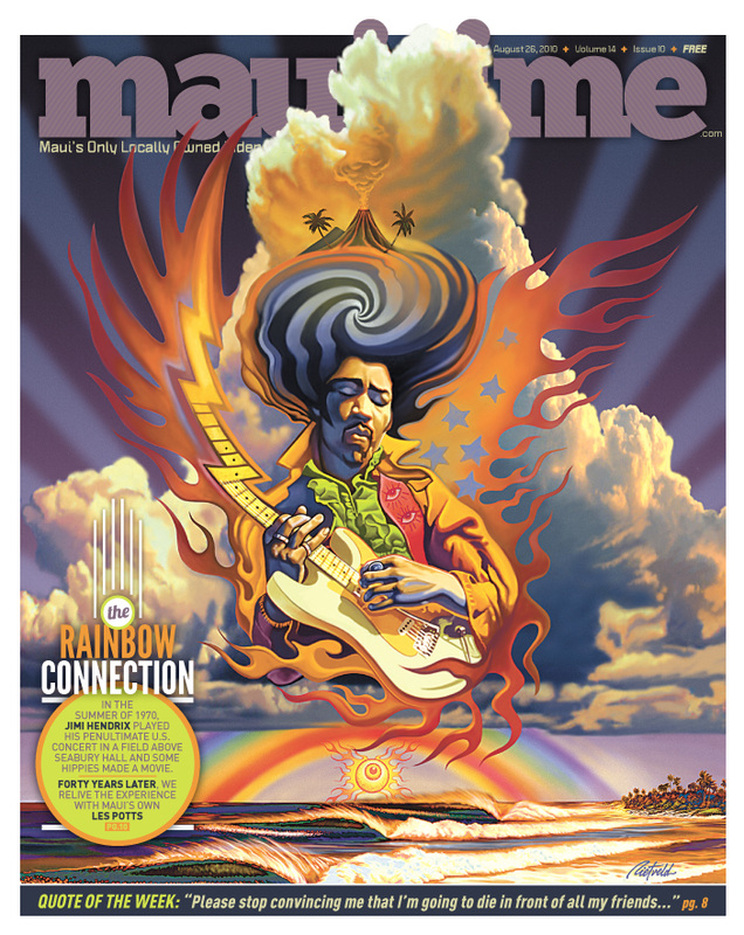

http://mauifeed.com/maui-news/remembering-rainbow-bridge-extended-mix/

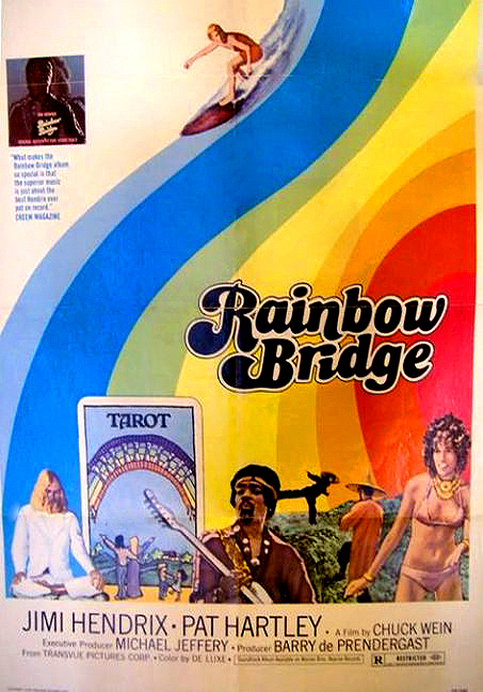

Rainbow Bridge is a 1972 film directed by Chuck Wein that features footage from a Jimi Hendrix concert, and a short piece of conversation between Pat Hartley, Wein and Hendrix. It was mainly financed by Hendrix manager Mike Jeffery, hence his appearance. The film is about Pat Hartley's "spiritual awakening" via a visit to the 'Rainbow Bridge' planetary meditation cult on Maui, where, as part of the proceedings Jimi Hendrix visits to play a concert during a 'Rainbow Bridge' mass meditation/colour/sound "experiment". The "Rainbow Bridge" concert was a free concert by Jimi Hendrix that was held on July 30, 1970, in a horse pasture above Seabury Hall, on the "Upcountry" slopes of Haleakala. The volcano makes up 75% of the island of Maui, Hawaii, although it probably last erupted in the 17th century, it is officially considered as being active.

Or, as Brother Bobby BEL describes it:

Leslie Potts turned on Jimi to LSD in 64 at the Golden Bear in Huntington Beach CA.

Mike Hynson chased Jimi around to do the movie. [see Hyson's story below]

I have the Aquarian Flag from the Zodiac around the stage.

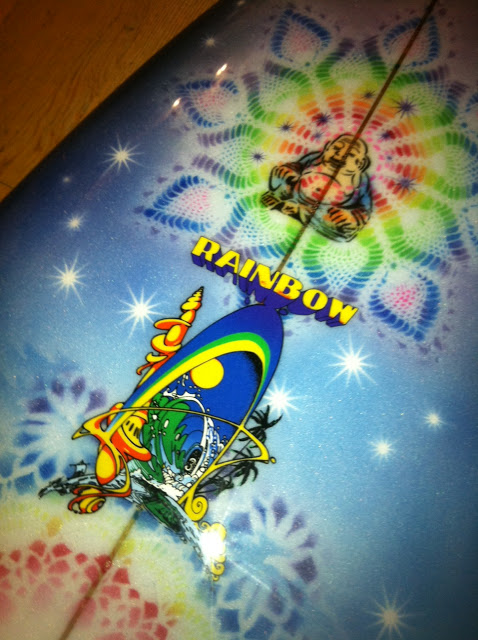

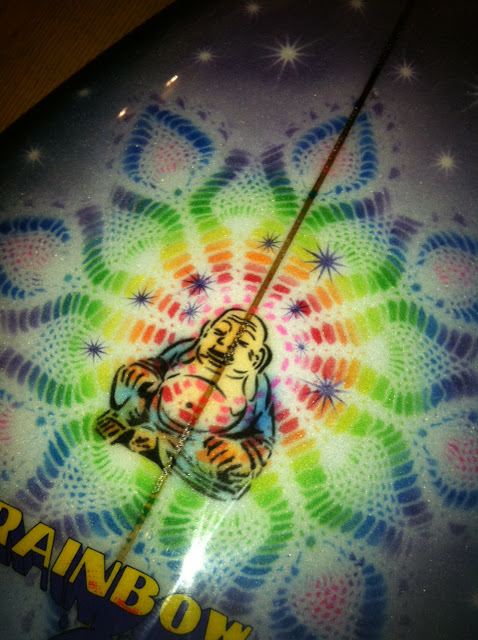

I have 2 Rainbow Surf Boards

The Brotherhood was on the FBI most wanted list and some had to hide out in the tent on the right of the stage with the Big Afghani Hookah. Jimi was down for his first set and Eddie Spaghetti gave him a hit of DMT; check out the 2nd set. He was in the Flow.

We had a Coffee Gallery in Pasadena called the "Euphoria" with my partners Bob Thomas and Buddy Morgan in 1965. Bob Did the Dead's Art logos and the Bear was making his first Acid . We tried it out.

I started booking bands to play and Long John and Jerry came down and blew some Tibetan horns.

40 of us got busted at the Euphoria on TV and Newspapers for interfering with a Police officer. I asked a plain clothes cop for a donation; they had a Bus and the press out side. Buddy and I were given a choice, cut our hair and probation or 6 months in the county jail. I was just back from Combat in the first offense in Viet Nam and told them who they thought they were telling to cut his hair? A Psychedelic Ranger? Buddy went to jail.

I went to Haight Ashbury as a fugitive for riding a freight train and not cutting my hair.

The Brotherhood was just Forming at that time at the French Quarters in Anaheim where the original Brotherhood came from. I ran into them in the 7th grade at John C. Fremont Jr. High 1957 Anaheim, Ca., home of Disneyland. There were a few of us fugitives hiding out from the the first snitches Vallalah Ashbrook from Anaheim in San Francisco.

We started the Aquarian Temple and studied to become ministers with the Universal Life Church.

1724 Waller St and Stanyon was our Temple and I became Chris Wheat the 1st Hippie Ministers in the Haight in the Newspapers and TV also Look and Life interviewed us.

Yeah, we hung out with Jimi, on mescaline, played some tunes and surfed. A great Time and a message to turn on to self realization, organic health, happy life that is so widely spread now.

Or, as Brother Bobby BEL describes it:

Leslie Potts turned on Jimi to LSD in 64 at the Golden Bear in Huntington Beach CA.

Mike Hynson chased Jimi around to do the movie. [see Hyson's story below]

I have the Aquarian Flag from the Zodiac around the stage.

I have 2 Rainbow Surf Boards

The Brotherhood was on the FBI most wanted list and some had to hide out in the tent on the right of the stage with the Big Afghani Hookah. Jimi was down for his first set and Eddie Spaghetti gave him a hit of DMT; check out the 2nd set. He was in the Flow.

We had a Coffee Gallery in Pasadena called the "Euphoria" with my partners Bob Thomas and Buddy Morgan in 1965. Bob Did the Dead's Art logos and the Bear was making his first Acid . We tried it out.

I started booking bands to play and Long John and Jerry came down and blew some Tibetan horns.

40 of us got busted at the Euphoria on TV and Newspapers for interfering with a Police officer. I asked a plain clothes cop for a donation; they had a Bus and the press out side. Buddy and I were given a choice, cut our hair and probation or 6 months in the county jail. I was just back from Combat in the first offense in Viet Nam and told them who they thought they were telling to cut his hair? A Psychedelic Ranger? Buddy went to jail.

I went to Haight Ashbury as a fugitive for riding a freight train and not cutting my hair.

The Brotherhood was just Forming at that time at the French Quarters in Anaheim where the original Brotherhood came from. I ran into them in the 7th grade at John C. Fremont Jr. High 1957 Anaheim, Ca., home of Disneyland. There were a few of us fugitives hiding out from the the first snitches Vallalah Ashbrook from Anaheim in San Francisco.

We started the Aquarian Temple and studied to become ministers with the Universal Life Church.

1724 Waller St and Stanyon was our Temple and I became Chris Wheat the 1st Hippie Ministers in the Haight in the Newspapers and TV also Look and Life interviewed us.

Yeah, we hung out with Jimi, on mescaline, played some tunes and surfed. A great Time and a message to turn on to self realization, organic health, happy life that is so widely spread now.

HENDRIX 'MODERN MASTERS' PBS FILM

http://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/episodes/jimi-hendrix/film-jimi-hendrix-hear-my-train-a-comin/2756/

http://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/episodes/jimi-hendrix/film-jimi-hendrix-hear-my-train-a-comin/2756/

Hear My Train A Comin’ unveils previously unseen performance footage and home movies taken by Hendrix and drummer Mitch Mitchell while sourcing an extensive archive of photographs, drawings, family letters and more to provide new insight into the musician’s personality and genius. The two-hour film uses Hendrix’s own words to tell his story, illustrated through archival interviews and illuminated with commentary from family, well-known friends and musicians including Paul McCartney, band members Noel Redding, Mitch Mitchell, Billy Cox, long-time sound engineer Eddie Kramer; Steve Winwood, Vernon Reid, Billy Gibbons, Dweezil Zappa and Dave Mason.

The film also features revealing glimpses into Jimi and his era from the three women closest to him: Linda Keith (the girlfriend who introduced Jimi to future manager Chas Chandler), Faye Pridgon (who befriended Hendrix in Harlem in the early 1960s) and Colette Mimram (one of the era’s most influential fashion trendsetters who provided inspiration for Hendrix’s signature look and created such memorable stage costumes as the beaded jacket Hendrix famously wore at Woodstock).

Among the previously unseen treasures in Hear My Train A Comin’ is recently uncovered film footage of Hendrix at the 1968 Miami Pop Festival. American Masters: Jimi Hendrix – Hear My Train A Comin’ is a production of Fuse Films and THIRTEEN’s American Masters in association with WNET. Bob Smeaton is director.

The film also features revealing glimpses into Jimi and his era from the three women closest to him: Linda Keith (the girlfriend who introduced Jimi to future manager Chas Chandler), Faye Pridgon (who befriended Hendrix in Harlem in the early 1960s) and Colette Mimram (one of the era’s most influential fashion trendsetters who provided inspiration for Hendrix’s signature look and created such memorable stage costumes as the beaded jacket Hendrix famously wore at Woodstock).

Among the previously unseen treasures in Hear My Train A Comin’ is recently uncovered film footage of Hendrix at the 1968 Miami Pop Festival. American Masters: Jimi Hendrix – Hear My Train A Comin’ is a production of Fuse Films and THIRTEEN’s American Masters in association with WNET. Bob Smeaton is director.

Jimi had been dead a year, but the revolution--or at least a movie version of it--kept right on jammin' without him.

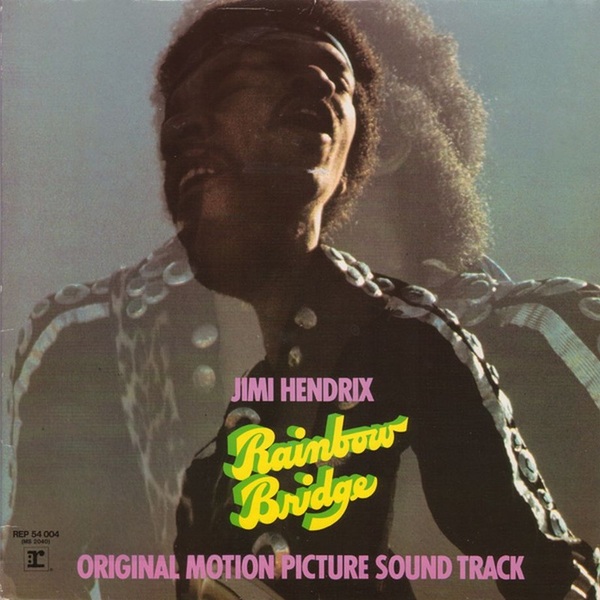

Less than a month after Hendrix played a free concert on the slopes of Mt. Haleakela, effectively wrapping principal photography for Rainbow Bridge, the flamboyant rock virtuoso accidentally self-immortalized on a deadly cocktail of red wine and barbiturates, choking on his own vomit in a London flat on September 18, 1970.

Within days of Hendrix's death, Mike Hynson, former '60s teen surf prodigy turned indie film producer, got the call from Warner Brothers Studios demanding immediate return of all original footage of Hendrix shot to date. With the lawyers circling, Hynson knew he had to move fast or lose Rainbow Bridge forever. Warner had not only funded the film--a rambling cinematic "happening" loosely based around a spiritual surfing quest--but they also controlled most of Hendrix's music slated for the film's soundtrack.

Hynson returned the canned footage. However, unbeknownst to the Warner suits, Hynson and director Chuck Wein had stashed a working print of Rainbow Bridge for safety.

By late 1971, Hynson had raised enough discreet venture capital to wrangle verbal clearance of Hendrix's music from Warner Brothers and keep his cinematic problem child on life support. After chopping the film down from a six-hour rough cut to 125 minutes, he and Wein took their movie out on the road for a short bootleg tour throughout the Southwest. Lacking a distributor, they went the traditional surf film four-wall route, hiring the halls themselves and advertising the day of the show via hastily Xeroxed handbills.

Early reviews of Rainbow Bridge had been ... mixed. The La Jolla surf tribe, many of its members Hynson's brethren from the old Windansea Surf Club days, lit up and loved it. But in Tucson, AZ, the local paper ran a shrill front-page editorial the day after the premiere, warning parents to keep their kids from seeing the film lest the graduating class of Tucson High, cheerleaders and all, run off en masse to Maui to join a drugged-out occult surfing hippie commune.

Which is to say that Hynson and Wein had achieved something approaching art.

By the time they hit Laguna, a palpable underground buzz preceded them. Around midnight, outside the venerable South Coast Cinema, a large crowd massed on PCH for a sneak-peek premiere. Johnny Gale, laughing long-haired elder of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love--a freewheeling crew of spiritual seekers and psychedelic buccaneers--was thoroughly enjoying his birthday party, handpicking the audience at the door to make sure only the most righteous dudes and prettiest girls came through. Several ornate airbrushed boards, all shaped by Mike Hynson, were displayed in the lobby like geodesic trophy kills. These boards--thick pintails featuring severe downrails from nose to tail--were stars in their own right, having been featured throughout the film's surfing sequences.

The premiere was Hynson's present to Gale, a spiritual fellow traveler and brother surfer. The son of a well-to-do Newport marine engineer, the diminutive Gale was a charismatic and flamboyant LSD baron, known to chum the crowd at rock concerts by flinging handfuls of Orange Sunshine tabs--the Brotherhood's premier acid--like dragon seeds to the cheering throngs. Within a few short years, Gale had amassed a fortune through illegal drug sales. Hynson, who bore a passing resemblance to the blond, shoulder-tressed Gale, connected with him years earlier, and by 1969 they'd gone into business together as Rainbow Surfboards in Laguna Beach.

Sprinkled throughout the milling crowd were several federal drug enforcement agents, some in hippie camouflage. Likely among them was Neil Purcell, a young Laguna Beach police officer who was looking to make his career by bringing down the Brotherhood. The agents took notes and methodically built their case against Gale and his drug-running cohorts, who thus far had outfoxed authorities at nearly every turn. This included Hynson, age 28, who had been associated with the Brotherhood since its arrival in Laguna in the mid-'60s.

Paying attention to the music used in surfing films reveals that, by the end of the 1960s, many surfers shunned the now passé vocal and instrumental versions of surf music, and, like many young people at the time, favored psychedelic rock, and even early punk, which seemed to better fit with newer styles of surfing on shorter boards. For example, Jimi Hendrix was favored by many surfers, as is implied in the 1972 film, Rainbow Bridge, in which both Hendrix and surfer Mike Hynson (one of the two lead surfers in Endless Summer) are featured.

Later, films made by and for surfers do occasionally use early 1960s style surf music, but usually to reference older 1960s longboarding styles. The 1960s naming of a genre “surf music” may have even hindered subsequent musical surfers, since so many people believed any surfer would naturally prefer “surf music.” Though a number of notable surfers are also accomplished musicians, and there are professional musicians who are accomplished surfers[, it was not until Jack Johnson turned his attention from competitive surfing and surf films to performing and recording his own songs that a prominent connection between popular music and surfing and a surfing lifestyle was renewed. http://surfingsafari.wordpress.com/background/impact-of-surf-films/

|

|

|

Facts: Hendrix wasn’t a junkie, but dabbled and tried to stay away from it by emigrating to Hawai to be with the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, whose members also infiltrated [Hare Krishnas] Iskcon (for good or bad depending how one views countercultural outlaw heroes). The brotherhood, as seen in the Rainbow Bridge film, are connected to devotees (as one sees them actually doing sankirtana in the film) and they shunned junk and were into LSD and ganja as sacraments and the spiritual and mystical, like Hendrix. He didn’t actually decide on the album cover of Axis Bold as Love, and the painting wasn’t authorized by him but put there anyway.

If the management scene of the Hendrix world had not dragged him back to mainland USA, he would have stayed with the Brotherhood in Hawaii, away from junk and towards a spiritualish life, which one can see he clearly leaned towards. But he was pulled away from the brothers to the mainland and the tour machine and he never made it back to Hawaii in the end but rather to the crematorium.

He visioned the bringing together of classical music and the blues-jazz, sky church music, and was a deeply spiritual man who later shunned the rock n roll gimics, guitar with teeth, sexual pelvic thrusts etc, becoming bored with such shallow stagnated rebellion clichés. He wasn’t even a big drinker of alcohol and prefered reefer and acid to booze and smack and even sought to go beyond these.

"Rainbow Bridge" is important to ISKCON history in that the official ISKCON expose of the brotherhood links to ISKCON talk of the brotherhood being involved around Kulik in the 1975-1977 period in LA and Laguna. But here we see in "Rainbow Bridge" a link between the brotherhood and devotees, in this rather cryptic and encoded countercultural slice of film, if one looks at it deep enough, all in the late 1960s.

Try watching it keeping this in mind and see the references to Hare Krishna on the lips of the Rainbow brothers and on the car where the maha mantra is painted and also in the features of various devotees on the film itself. The question is which devotees and what temple and what is being symbolized here, a big acid and pot deal going on? Jayatirtha wasn’t the only one surely and neither was Rishabadev and co. Surely brotherhood chemists were interested in ISKCON, especially as its founder was once a big chemist and had lots of chemical company contacts even when ISKCON took off big in India.

http://www.gaudiya-repercussions.com/index.php?showtopic=2161&mode=threaded&pid=48222

If the management scene of the Hendrix world had not dragged him back to mainland USA, he would have stayed with the Brotherhood in Hawaii, away from junk and towards a spiritualish life, which one can see he clearly leaned towards. But he was pulled away from the brothers to the mainland and the tour machine and he never made it back to Hawaii in the end but rather to the crematorium.

He visioned the bringing together of classical music and the blues-jazz, sky church music, and was a deeply spiritual man who later shunned the rock n roll gimics, guitar with teeth, sexual pelvic thrusts etc, becoming bored with such shallow stagnated rebellion clichés. He wasn’t even a big drinker of alcohol and prefered reefer and acid to booze and smack and even sought to go beyond these.

"Rainbow Bridge" is important to ISKCON history in that the official ISKCON expose of the brotherhood links to ISKCON talk of the brotherhood being involved around Kulik in the 1975-1977 period in LA and Laguna. But here we see in "Rainbow Bridge" a link between the brotherhood and devotees, in this rather cryptic and encoded countercultural slice of film, if one looks at it deep enough, all in the late 1960s.

Try watching it keeping this in mind and see the references to Hare Krishna on the lips of the Rainbow brothers and on the car where the maha mantra is painted and also in the features of various devotees on the film itself. The question is which devotees and what temple and what is being symbolized here, a big acid and pot deal going on? Jayatirtha wasn’t the only one surely and neither was Rishabadev and co. Surely brotherhood chemists were interested in ISKCON, especially as its founder was once a big chemist and had lots of chemical company contacts even when ISKCON took off big in India.

http://www.gaudiya-repercussions.com/index.php?showtopic=2161&mode=threaded&pid=48222

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rainbow Surfboards got an unexpected publicity boost from Jimi Hendrix and Chuck Wein, a member of Andy Warhol's so-called Factory whom Merryweather had befriended while working as a model in New York. In 1972, while Hynson and Merryweather were living in Maui where most of the Brotherhood had relocated after Laguna Beach became too hot Merryweather suggested to Wein that he direct a Jimi Hendrix concert movie in Maui and even introduced him to Hendrix's manager, Michael Jefferey.

"Chuck wanted to make a movie that was going to have surfing, healers, vegetarians, New Age people, even a space woman," Merryweather says. "Jimi was going to play the music because he was at the top of his game, and Michael was going to surf because he was at the top of his game." The result, 1972's Rainbow Bridge, was billed as a Hendrix concert film because the concert Hendrix played in Maui provides the ending of the movie, much of which actually features surfing by Hynson and his friends, goofy-foot hotshot Dave Nuuhiwa and Leslie Potts. "Gale refused to be in the movie, because he didn't want to have his face on camera," Hynson recalls.

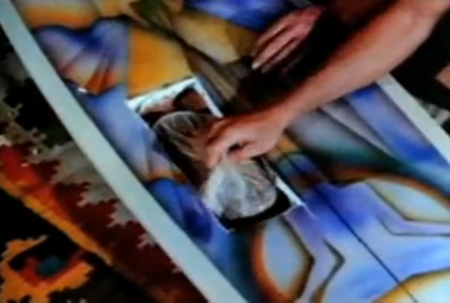

The film's most notorious scene features Hynson and Potts ripping open a Rainbow Surfboard to reveal a stash of hash, a stunt that takes place under a Richard Nixon poster that reads, "Would You Buy a Used Car From This Man?" When the film opened in Laguna Beach, Hynson gave Gale all the tickets as a birthday present. Half of the audience was rumored to be narcs. "The room smoked up so much you couldn't see the stage," Hynson says. "We had all these Rainbow Surfboards up on the stage, and when the movie showed the board being opened up, it got the police crazy. They were constantly on our ass. Anybody who had a Rainbow Surfboard got pulled over."

* * *

A few months after Rainbow Bridge came out, a multi-agency task force arrested dozens of members of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love in California, Oregon and Maui, including Gale, who spent the next several months in prison. "He wasn't in for long," Hynson says. "He was like a rabbit." But thanks in part to the Brotherhood's legendary secrecy, the police never knew Hynson's role in the group. Once Gale got out of prison, the two continued to sell surfboards and market the Rainbow brand by opening a Rainbow Juice bar in La Jolla with help from Merryweather. But the business folded after just a few years. "We didn't shortchange anything," Merryweather says. "We got an accounting firm and figured out we were paying people 25 cents to eat the avocado sandwiches."

Meanwhile, Gale had become the biggest cocaine broker in California. Hynson says he didn't know the full extent of Gale's business dealings, but he does recall visiting his friend's house one time when Gale suddenly remembered that a truck full of Colombian marijuana was on its way from Florida. He also recalls that whenever he rode in Gale's car, someone always seemed to be following them. "Not for long, though," Hynson says. "Gale didn't stick around long enough for anyone to chase him."

On June 2, 1982, Gale perished when the car he was driving, Hynson's Mercedes, went off the road in Dana Point. Hynson remains convinced someone either the cops or rival criminals was chasing his friend. The tragedy ended Rainbow Surfboards (it's recently been reincarnated under new ownership) and left Hynson financially strapped. "If you ever had a business project and you're wondering whatever happened to it, it's probably because the other guy is dead," Hynson jokes.

Gale's death devastated Hynson, says Merryweather. "I wasn't with him at the time, but people told me they'd never seen Michael take anything so bad. He just really went sideways."

http://sixties-l.blogspot.com/2009/07/tales-of-brotherhood-of-eternal-love.html

"Chuck wanted to make a movie that was going to have surfing, healers, vegetarians, New Age people, even a space woman," Merryweather says. "Jimi was going to play the music because he was at the top of his game, and Michael was going to surf because he was at the top of his game." The result, 1972's Rainbow Bridge, was billed as a Hendrix concert film because the concert Hendrix played in Maui provides the ending of the movie, much of which actually features surfing by Hynson and his friends, goofy-foot hotshot Dave Nuuhiwa and Leslie Potts. "Gale refused to be in the movie, because he didn't want to have his face on camera," Hynson recalls.

The film's most notorious scene features Hynson and Potts ripping open a Rainbow Surfboard to reveal a stash of hash, a stunt that takes place under a Richard Nixon poster that reads, "Would You Buy a Used Car From This Man?" When the film opened in Laguna Beach, Hynson gave Gale all the tickets as a birthday present. Half of the audience was rumored to be narcs. "The room smoked up so much you couldn't see the stage," Hynson says. "We had all these Rainbow Surfboards up on the stage, and when the movie showed the board being opened up, it got the police crazy. They were constantly on our ass. Anybody who had a Rainbow Surfboard got pulled over."

* * *

A few months after Rainbow Bridge came out, a multi-agency task force arrested dozens of members of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love in California, Oregon and Maui, including Gale, who spent the next several months in prison. "He wasn't in for long," Hynson says. "He was like a rabbit." But thanks in part to the Brotherhood's legendary secrecy, the police never knew Hynson's role in the group. Once Gale got out of prison, the two continued to sell surfboards and market the Rainbow brand by opening a Rainbow Juice bar in La Jolla with help from Merryweather. But the business folded after just a few years. "We didn't shortchange anything," Merryweather says. "We got an accounting firm and figured out we were paying people 25 cents to eat the avocado sandwiches."

Meanwhile, Gale had become the biggest cocaine broker in California. Hynson says he didn't know the full extent of Gale's business dealings, but he does recall visiting his friend's house one time when Gale suddenly remembered that a truck full of Colombian marijuana was on its way from Florida. He also recalls that whenever he rode in Gale's car, someone always seemed to be following them. "Not for long, though," Hynson says. "Gale didn't stick around long enough for anyone to chase him."

On June 2, 1982, Gale perished when the car he was driving, Hynson's Mercedes, went off the road in Dana Point. Hynson remains convinced someone either the cops or rival criminals was chasing his friend. The tragedy ended Rainbow Surfboards (it's recently been reincarnated under new ownership) and left Hynson financially strapped. "If you ever had a business project and you're wondering whatever happened to it, it's probably because the other guy is dead," Hynson jokes.

Gale's death devastated Hynson, says Merryweather. "I wasn't with him at the time, but people told me they'd never seen Michael take anything so bad. He just really went sideways."

http://sixties-l.blogspot.com/2009/07/tales-of-brotherhood-of-eternal-love.html

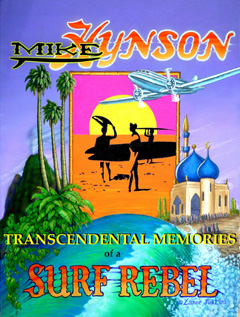

Hynson

Excerpt

CHAPTER 38

THE ROAD TO RAINBOW BRIDGE

http://www.authorsden.com/visit/viewwork.asp?id=44468

Melinda and I were relaxing with Terry and Nina Stafford on their lanai on Front Street in Lahaina. Melinda's crush on Terry was buried long ago and we all become good friends. We even had an invitation to stay with them any time we were in town. Maui was also the place I came whenever I needed peace and quiet and boy did I need it, thanks to the shitty week I had back home in San Diego.

Michael, Jimi Hendrix' Manager is here, Les Potts burst onto the Stafford's patio almost out of breath. He's at the Pioneer and he wants to buy some acid. Les hightailed it over from the Inn as fast as possible where he and his sun-scorched friends had been trying to hustle someone into loaning them ten grand to open a surf shop. When a middle-aged Englishman with thick coke-bottle glasses, kind of an Austin Powers look-alike, walked up to their table and introduced himself as Hendrix' manager, nobody believed him. But when he mentioned he was interested in investing in their idea, suddenly the guys were all ears. The man then pulled out a small tape recorder to play some of Jimi's new songs and asked where he could score some pot or acid.

Why wouldn't I believe Les? He was this scrappy toe-headed surfer from Huntington Beach that I met at one of the Sunday Sessions and made boards with for a while.

* * * *

Mid-sixties, Hynson was the shaper, says Les. Although I'd studied Sonny Vardemen, Gordie, and Mike Marshall, I was busy trying to figure out what designs would work. Mike already knew. I was still hungry for information so I studied his every move. Shaping is one of those art forms where there is no school. You have to learn hands-on as an apprentice under a master.

* * * *

Les was also part of my crew on Maui. He'd been over in the Islands for a couple of years now after he got out of the service and we usually hooked up when I'd get into town. So it wasn�t strange when he showed up at the Staffords. The coincidence was that he brought up Hendrix after everything I�d been through the week before. I reached in my pocket for some Orange Sunshine, pulled out my stash, and gave Les three hits. Go back to the Pioneer and tell him no charge.

Things started getting shitty nine days earlier when I woke up to a radio announcement in La Jolla. Jimi Hendrix was playing that night at the San Diego Sports Arena. After years of listening to the sounds of Hendrix, from my first splash at the Monterey Pop Festival where he burned his stick, to blowing his arms off at the concerts up in Frisco, Hendrix' music has always been the lead in this psychedelic free-from style of John Coltrane. I felt his style of rock and roll was really a movement, an expression of the human soul and it jived well with the feeling that surfing provided.

Hendrix was just the sound I needed for a surf demo I was making for Bill Bahne. It all started when I passed on an idea to him that George Downing came up with for a replaceable fin. It wasn't like I was ripping George off. There were no existing patent restrictions and Bahne agreed to pay him royalties. Now I'm pretty spontaneous when it comes to designing boards and Bahne, well he's the mathematician. With his keen business sense and an incredible engineering ability, the fin box was introduced through Fins Unlimited.

CHAPTER 38

THE ROAD TO RAINBOW BRIDGE

http://www.authorsden.com/visit/viewwork.asp?id=44468

Melinda and I were relaxing with Terry and Nina Stafford on their lanai on Front Street in Lahaina. Melinda's crush on Terry was buried long ago and we all become good friends. We even had an invitation to stay with them any time we were in town. Maui was also the place I came whenever I needed peace and quiet and boy did I need it, thanks to the shitty week I had back home in San Diego.

Michael, Jimi Hendrix' Manager is here, Les Potts burst onto the Stafford's patio almost out of breath. He's at the Pioneer and he wants to buy some acid. Les hightailed it over from the Inn as fast as possible where he and his sun-scorched friends had been trying to hustle someone into loaning them ten grand to open a surf shop. When a middle-aged Englishman with thick coke-bottle glasses, kind of an Austin Powers look-alike, walked up to their table and introduced himself as Hendrix' manager, nobody believed him. But when he mentioned he was interested in investing in their idea, suddenly the guys were all ears. The man then pulled out a small tape recorder to play some of Jimi's new songs and asked where he could score some pot or acid.

Why wouldn't I believe Les? He was this scrappy toe-headed surfer from Huntington Beach that I met at one of the Sunday Sessions and made boards with for a while.

* * * *

Mid-sixties, Hynson was the shaper, says Les. Although I'd studied Sonny Vardemen, Gordie, and Mike Marshall, I was busy trying to figure out what designs would work. Mike already knew. I was still hungry for information so I studied his every move. Shaping is one of those art forms where there is no school. You have to learn hands-on as an apprentice under a master.

* * * *

Les was also part of my crew on Maui. He'd been over in the Islands for a couple of years now after he got out of the service and we usually hooked up when I'd get into town. So it wasn�t strange when he showed up at the Staffords. The coincidence was that he brought up Hendrix after everything I�d been through the week before. I reached in my pocket for some Orange Sunshine, pulled out my stash, and gave Les three hits. Go back to the Pioneer and tell him no charge.

Things started getting shitty nine days earlier when I woke up to a radio announcement in La Jolla. Jimi Hendrix was playing that night at the San Diego Sports Arena. After years of listening to the sounds of Hendrix, from my first splash at the Monterey Pop Festival where he burned his stick, to blowing his arms off at the concerts up in Frisco, Hendrix' music has always been the lead in this psychedelic free-from style of John Coltrane. I felt his style of rock and roll was really a movement, an expression of the human soul and it jived well with the feeling that surfing provided.

Hendrix was just the sound I needed for a surf demo I was making for Bill Bahne. It all started when I passed on an idea to him that George Downing came up with for a replaceable fin. It wasn't like I was ripping George off. There were no existing patent restrictions and Bahne agreed to pay him royalties. Now I'm pretty spontaneous when it comes to designing boards and Bahne, well he's the mathematician. With his keen business sense and an incredible engineering ability, the fin box was introduced through Fins Unlimited.

http://www.surfysurfy.net/2012/10/rainbow-hynson-starman.html

Mike Hynson & BEL

What’s missing from Hynson's Technicolor trip down memory lane are the past 20 or so years of his life. It’s a stretch of time Hynson doesn’t talk about much, partly because he’s not proud of it, but mostly because he doesn’t remember it well, even less so than the heady days of the late-1960s, when he was dropping acid nearly every day with his friends in the Laguna Beach-based band of smugglers known as the Brotherhood of Eternal Love (see “Lords of Acid,” July 8, 2005). Those were strange times indeed, but a lot of fun compared to what came next. In the early 1980s, life went downhill for Hynson when John Gale, one of the Brotherhood’s best surfers and Laguna Beach’s most legendary outlaws, died in a mysterious car crash, thus ruining Hynson emotionally and financially.

Gale was Hynson’s business partner in Rainbow Surfboards, which the two founded in Laguna Beach in 1969, as well as his best friend. Hynson’s drug-addled, rebellious lifestyle had already led to a divorce from wife Melinda Merryweather, a Ford Agency model, actress and art designer, but Gale’s death seemed to push him over the edge from reckless to beyond help. He descended into a depression and drug addiction that lasted decades, ruining his surfing career and alienating him from everyone but his closest friends until only a few years ago.

Now 67, Hynson is muscular and trim from long days spent shaping boards for mostly Japanese customers. He still has a full head of hair, which is pulled back over his scalp into a short Native American-style braid. He’s wearing a black T-shirt adorned with a red Chinese dragon, dusty black jeans and rugged work boots. His face is full of color and breaks easily into a self-deprecating grin. Gone are the gaunt physique and haggard expression on display in photographs taken of him just a decade ago, when People profiled him in an embarrassing article titled “The Endless Bummer.” (The story noted that just a few weeks before Endless Summer 2 was released, Hynson was serving jail time for drug possession.)

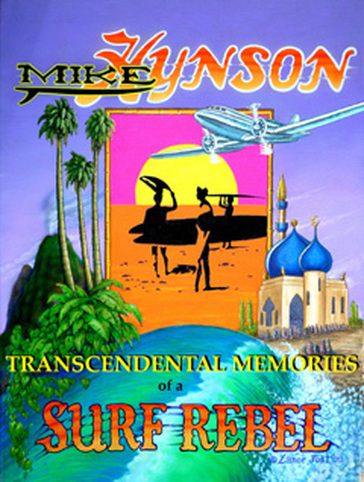

It was during one of Hynson’s numerous jail stints, at some point in the 1980s—he’s not sure what year or why he was in jail—that somebody suggested he use his free time to write, a suggestion that, two decades later, led to Transcendental Memories of a Surf Rebel, an autobiography Hynson co-wrote with Donna Klaasen that was released this month by the Dana Point-based Endless Dreams Publishing. Among other things, the book divulges that Hynson, who has never spoken publicly about the Brotherhood, wasn’t just pals with them, but actually instructed them in the art of using surfboards to smuggle drugs.

“The last time I’d been in jail, I’d started reading for the first time in my life,” Hynson recalls of his autobiographical efforts. “And on this stretch, I just got obsessed with writing.” By the mid-1990s, Hynson had cranked out hundreds of pages of handwritten memoirs, all of it scrawled in pencil on jailhouse paper, which he eventually shared with a few friends at the surf shop down the street from where he now lives, a half-mile from the beach in Encinitas. “A couple of people looked at it and said, ‘Michael, I know you can understand this, but I look at it and I can’t understand a word,’” he says.

Hynson remembers glancing down at the first draft of his autobiography. For the first time, he realized that, after the first few pages, his magnum opus consisted of nothing but incomprehensible chicken-scratch scrawl, less a series of words and punctuation marks than a never-ending pattern of zigzag lines, like heart-monitor readings. “It was just so dysfunctional,” he says, chuckling.

* * *

Unlike the blurry events of the past few decades, the highlights of Hynson’s early life are still very vivid in his mind. Michael Lear Hynson was born in the Northern California coastal town of Crescent City in 1942, a Navy brat whose father survived kamikaze attacks as a radioman in World War II. Mike grew up in San Diego and Hawaii, never staying in one place long enough to make friends. His thrill-seeking lifestyle began while living with his mother at a trailer park when he was just 2 years old.

One morning, he crawled out the door while his mother wasn’t looking and discovered that the trailer next door had moved. He grabbed a 250-volt electrical plug that was lying on the ground and stuck it in his mouth. According to Hynson, the shock split his tongue and made it hard for him to learn how to speak. “I developed my own unique way of talking, and sometimes, I mumble and stumble,” he says. “Then, when I was 5, I was climbing these stairs at Imperial Beach, and this friend of mine had a hammer in his hand. My mother said something behind us, and he turned, and the claw of the hammer went right into the temple of my head.”

The next thing Hynson knew, he was being flown by helicopter to San Diego’s nearby naval base. He remembers floating above himself, looking down at his body surrounded by doctors, all of whom left the room. “I remember being really comfortable and just tripping, you know,” he says, “and then my mother turned around to leave the room, and I screamed into my body, ‘Where are you going?’ And my mother goes, ‘He’s alive!’ and the doctors came back in, and they got me back.” Hynson says he likes to joke that the hammer incident explains why he often seems to lose his train of thought nowadays. “Everybody who knows me knows that I go off on tangents,” he says. “But I’m just making an excuse for myself.”

Hynson spent most of his elementary-school years in Honolulu, where, he says, he never picked up a surfboard. It wasn’t until he was in junior-high school in San Diego that he took up surfing with some older kids who surfed at Pacific Beach, called themselves the Sultans and wore matching purple-nylon jackets. After watching the older kids a few times, he borrowed a board. Hynson recalls standing up on his first wave, not realizing how fast he was moving until he looked at the nearby pier and saw wooden posts rushing by in a blur. “I’ll never forget it,” he says. “It was so far out. I couldn’t sleep, and I just got into it, borrowing boards and stealing them and everything.”

Stealing surfboards is how Hynson met the man who would give him his first big break in the world of surfboard shaping, Hobie Alter, an early surf pioneer and inventor of the Hobie Cat, which is now the world’s top-selling small catamaran. “I first met Mike when he stole some of my boards,” Alter says. “The cops wanted to press charges, but Linda Benson, one of the finest surfer gals, called me and said Mike wasn’t that bad.” Alter agreed to drop the charges if Hynson would return the boards and later gave him a job as a shaper.

Hynson’s first board was an 11-foot plank of balsa wood that he spotted while collecting weeds in the front yard of a house in Mission Beach. The board’s owner told him he could have the board if he wanted it, so Hynson and a friend lugged it to the friend’s garage, where Hynson began whittling away. “I had no idea what I was doing, and his parents were getting angry because of all this dust and resin and mess, but it turned out to be a 7-foot-11-inch board. It was a hot little board, and everyone loved it who rode it.”

Hynson suddenly found his board-shaping skills very much in demand. He became a top shaper for Gordon and Smith Surfboards in San Diego, where he designed and produced his trademark “RedFin” boards. He also began hanging out with all the best surfers in Southern California, including Corky Carroll, Phil Edwards, Nat Young and Robert August. “As a surfer, Mike was very good,” recalls Carroll, now TheOrange County Register’s surfing columnist. “He was not a guy that you had to worry about beating you in a contest, but he knew how to ride a wave. He also had a kind of charisma about him that seemed to attract ‘followers,’ so to speak.”

One person who began following Hynson’s surf career was Bruce Brown, a film director who, by the early 1960s, was filming all the big surf contests in Southern California and Hawaii. According to Hynson, Brown was getting tired of the fact that all the surf movies being made showed the same group of surfers on the same group of waves. “There was no story to any of these movies,” Hynson says. Brown came up with the concept of taking two surfers—one blond and right-footed (Hynson) and one dark-haired goofy-footer—August fit the part—and following them around the world, from California to Europe and Africa, in search of the perfect wave.

The details of their epic quest, which culminates with Hynson surfing a beautiful right-breaking wave at Cape St. Francis in South Africa, are familiar to anyone who has seen The Endless Summer, which remains iconic more than 40 years later. The film not only exposed the sport to a nationwide audience, helping export the industry beyond California and Hawaii, but it also helped shift the sport itself from a handful of well-known beaches to a constant quest for pristine waves in exotic locales. Hynson recalls the trip as one of the most fun adventures in his life, although part of the sense of adventure was the fact that he smuggled an ounce of pot with him as he flew around the world.

“I was young, stupid and loaded,” Hynson says. “I smoked pot everywhere. I had a roll of bennies, which I took with me also, so when we had to drive somewhere, guess who stayed up all night?”

Before the movie was released theatrically in 1966, Hynson accompanied Brown and August, as well as several other surf legends, including Carroll, on a nationwide road trip to promote the film. “We’d go into towns, and every time we’d stop for gas, Corky and I would jump out and go skateboarding,” Hynson says. “We really caused a scene because skateboarding hadn’t reached the inner part of the States yet.” As the trip wore on, the audiences were growing larger, and before Hynson realized it, the movie had become a hit. (At latest count, The Endless Summer has grossed $30 million.) Hynson claims that Brown had promised him and August that if the movie did well, everyone would share in the good fortune.

“It wasn’t until I grabbed Robert and went to LA and talked to a lawyer that I realized this guy was fucking me left and right,” Hynson says. In fact, Hynson had only become suspicious after his then-girlfriend Merryweather, whom he had just met at San Diego’s Windansea beach, asked him about his allowing Brown to use his likeness on film. “He’d never signed a release,” says Merryweather, now a civic activist in La Jolla. Merryweather’s father, Hubert, was the president of Arizona’s state senate; Barry Goldwater was her godfather. “I told Mike my father knew a great lawyer up in Hollywood, and let’s go up and see him.”

Hynson brought August with him to see the attorney, who insisted they each deserved a third of the profit from The Endless Summer. Hynson claims Brown refused to do that, instead offering each surfer $5,000, a new car and help getting set up in business. While August accepted the deal, Hynson says, he refused. (Neither Brown nor August responded to written requests for comment for this story, but Alter says Brown gave Hynson the gift of fame he still enjoys. “Nobody knew who Mike was back then,” he says. “Bruce took all the risk, and I’ve never met anybody more forthright and honest.”) The dispute ended Hynson’s friendships with Brown and, eventually, August. Enraged by what he felt was Brown’s betrayal, Hynson dropped out for a while, leaving California with Merryweather to spend half a year surfing big waves on Oahu’s North Shore.

* * *

One of the surfers Hynson got to know in Hawaii was Chuck Mundell, a high-school dropout from Huntington Beach. Mundell admired Hynson and wanted him to meet a good friend of his named John Griggs, who was living with a bunch of friends in a stone building in Orange County’s Modjeska Canyon. Griggs and his friends, most of whom were former boozers, brawlers and heroin addicts from Anaheim, had begun experimenting with a new drug that Griggs had stolen at gunpoint from a Hollywood film producer: lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD).

Until October 1966, acid was legal in California, and Griggs and his group, who called themselves the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, believed that just as it had cured them of their addictions and violent behavior, it could also transform American society into a glorious utopia. They were heavily influenced by Harvard professor Timothy Leary, he of the famous exhortation “Turn on, tune in, drop out”—and who would later describe Griggs as the “holiest person who has ever lived in this country.”

Before Griggs invited Leary to join his group, which in early 1967 moved south to Laguna Canyon, to a neighborhood Griggs would christen “Dodge City” because of the constant skirmishes with the local forces of law and order, Hynson was Griggs’ most famous disciple. “Griggs had gold flashing out of his eyes and tongue, these words; he was just a magical little guy,” Hynson says. Accompanied by Merryweather, Hynson dropped his first acid with Griggs and several other Brotherhood members at Black’s Beach near La Jolla.

The experience brought him back to the hospital room where he’d nearly died as a child. It took Hynson a few trips to get beyond that near-death experience, but when that happened, he felt reborn with a new sense of spiritual purpose. “Those guys turned me on,” he says. “Things were happening. I remember Johnny and I walking down Haight-Ashbury [in San Francisco], and he got some acid from somebody, and the whole street was loaded with people doing their own hippie thing. It was really going on.”

Griggs had a plan: open a psychedelic spiritual and cultural center in Laguna Beach that would turn the town into a Southern California version of Haight-Ashbury. To finance the construction of Mystic Arts World, the store that would serve as that center, Griggs relied on cash from the Brotherhood’s burgeoning marijuana-smuggling operation.

“One day, I walked into this warehouse with Johnny and saw 50 tons of pot,” Hynson says. “I wasn’t supposed to see it, but I was there. I remember thinking, ‘It’s not going to get any better than this, and it’s not going to get any worse.’”

But Hynson had another idea for how Griggs could raise money: Why not use surfboards to smuggle hash from the Middle East or India? After all, nobody knew anything about surfing in India, so customs wouldn’t know if, for example, a surfboard weighed 20 or 30 pounds more than it should. Hynson suggested the idea to Griggs’ friend Dave Hall, who promptly borrowed a board and set off for Nepal, returning a few weeks later with the board—and the best hash anyone in Laguna Beach had ever smoked.

On his next trip, Hall invited Hynson to come along, which is how Hynson found himself struggling to fill three surfboards with hash oil late one night in New Delhi. The trip was a success, and the cash raised helped make Griggs’ dream a reality. “I wasn’t going to sell it or anything,” Hynson says. “I just gave it to those guys, and it bankrolled Mystic Arts. It was an honor, you know.”

* * *

During the next several years, the Brotherhood of Eternal Love established itself as both America’s top hashish-smuggling ring—with up to a dozen hash-stuffed Volkswagen buses and Land Rovers being shipped back from Afghanistan at any given moment—and the country’s top LSD-distribution ring. Leary moved to Laguna Beach and later accompanied Griggs to a mountain commune in Idyllwild, where Griggs died of an overdose of crystallized psilocybin in August 1969. Hynson stayed away from Dodge City as much as possible because Leary and the Brotherhood attracted too much heat.

He let his guard down once, however, when he and Merryweather sped through Laguna Canyon smoking a joint. A cop pulled them over, smelled the weed and arrested them both. At the station, the officer rifled through Merryweather’s belongings. “In my purse, I had a little Buddha, a prayer book and beads, some patchouli oil and incense, and a Murine bottle full of LSD,” Merryweather recalls. “The cop ingested it through his fingers and never got around to booking us.” In the morning, another officer arrived at the station, slack-jawed at the sight of his colleague, who reeked of patchouli, sitting with glazed eyes in front of a Buddha. “They let us the hell out of there right away,” Hynson says.

Not surprisingly, much of the late 1960s is a blur to Hynson. “It’s a fog,” he says. “There are a few years when I know I was there, but I don’t know what happened.” Although Griggs’ untimely death saddened Hynson, he’d already become best friends with a talented young surfer who also happened to be Dodge City’s biggest drug dealer, John Gale. In 1969, the two opened their own company, Rainbow Surfboards. Theirs were among the first truly shredding shortboards to hit the waves in Southern California and Hawaii. “Mike was one of the surfboard shapers in the 1960s who could make boards that worked,” recalls Carroll. “There were better craftsmen around, guys who could make ‘perfect boards,’ but Mike had the gift to make ones that just rode great.’”

Rainbow Surfboards got an unexpected publicity boost from Jimi Hendrix and Chuck Wein, a member of Andy Warhol’s so-called Factory whom Merryweather had befriended while working as a model in New York. In 1972, while Hynson and Merryweather were living in Maui—where most of the Brotherhood had relocated after Laguna Beach became too hot—Merryweather suggested to Wein that he direct a Jimi Hendrix concert movie in Maui and even introduced him to Hendrix’s manager, Michael Jefferey.

“Chuck wanted to make a movie that was going to have surfing, healers, vegetarians, New Age people, even a space woman,” Merryweather says. “Jimi was going to play the music because he was at the top of his game, and Michael was going to surf because he was at the top of his game.” The result, 1972’s Rainbow Bridge, was billed as a Hendrix concert film because the concert Hendrix played in Maui provides the ending of the movie, much of which actually features surfing by Hynson and his friends, goofy-foot hotshot Dave Nuuhiwa and Leslie Potts. “Gale refused to be in the movie, because he didn’t want to have his face on camera,” Hynson recalls.

The film’s most notorious scene features Hynson and Potts ripping open a Rainbow Surfboard to reveal a stash of hash, a stunt that takes place under a Richard Nixon poster that reads, “Would You Buy a Used Car From This Man?” When the film opened in Laguna Beach, Hynson gave Gale all the tickets as a birthday present. Half of the audience was rumored to be narcs. “The room smoked up so much you couldn’t see the stage,” Hynson says. “We had all these Rainbow Surfboards up on the stage, and when the movie showed the board being opened up, it got the police crazy. They were constantly on our ass. Anybody who had a Rainbow Surfboard got pulled over.”

* * *

A few months after Rainbow Bridge came out, a multi-agency task force arrested dozens of members of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love in California, Oregon and Maui, including Gale, who spent the next several months in prison. “He wasn’t in for long,” Hynson says. “He was like a rabbit.” But thanks in part to the Brotherhood’s legendary secrecy, the police never knew Hynson’s role in the group. Once Gale got out of prison, the two continued to sell surfboards and market the Rainbow brand by opening a Rainbow Juice bar in La Jolla with help from Merryweather. But the business folded after just a few years. “We didn’t shortchange anything,” Merryweather says. “We got an accounting firm and figured out we were paying people 25 cents to eat the avocado sandwiches.”

Meanwhile, Gale had become the biggest cocaine broker in California. Hynson says he didn’t know the full extent of Gale’s business dealings, but he does recall visiting his friend’s house one time when Gale suddenly remembered that a truck full of Colombian marijuana was on its way from Florida. He also recalls that whenever he rode in Gale’s car, someone always seemed to be following them. “Not for long, though,” Hynson says. “Gale didn’t stick around long enough for anyone to chase him.”

On June 2, 1982, Gale perished when the car he was driving, Hynson’s Mercedes, went off the road in Dana Point. Hynson remains convinced someone—either the cops or rival criminals—was chasing his friend. The tragedy ended Rainbow Surfboards (it’s recently been reincarnated under new ownership) and left Hynson financially strapped. “If you ever had a business project and you’re wondering whatever happened to it, it’s probably because the other guy is dead,” Hynson jokes.

Gale’s death devastated Hynson, says Merryweather. “I wasn’t with him at the time, but people told me they’d never seen Michael take anything so bad. He just really went sideways.”

Hynson spent the next two decades broke, strung out on coke and crystal methamphetamine, bouncing between jail and sleeping in alleys and garages in San Diego. “I got tripped up on my probation, you see,” he says, his voice trailing off as it often does when he attempts to make sense out of what happened to his life. “You know, it just snowballed. I hit rock-bottom, and then stayed there for a while.”

Hynson isn’t exactly sure how he finally managed to pull himself out of the downward spiral, although he credits ex-wife Merryweather and current girlfriend Carol Hannigan with being “angels” in his life. “It’s just been a gradual process of coming back to reality, and I haven’t stopped since,” he says. “One day, I realized I had a driver’s license with my own address and a telephone number. I even had a bank account. That’s when I realized I was back in society again.”

Thanks to the booming market for American-designed surfboards in Japan, Hynson is doing brisk business there. “There’s really no money in surfboards,” he says. “But thank God for the Japanese.” Meanwhile, Hynson hopes to sell the first 1,000 signed copies of his book for $350 each, which would raise enough cash to print many thousands of additional copies. Eventually, he wants to help publish art books by local artists such as Lance Jost and Bill Ogden, whom he’s known since his Laguna Beach days. “The more books we sell, the more the price goes down,” he says. “I don’t have any money right now, but I’m taking every cent I have, and we are just going to snowball this thing. If I can just get some juice, I’m going to have some fun.”

Nick Schou’, Orange Sunshine: The Brotherhood of Eternal Love and Its Quest to Spread Peace, Love, and Acid to the World, Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press.

Gale was Hynson’s business partner in Rainbow Surfboards, which the two founded in Laguna Beach in 1969, as well as his best friend. Hynson’s drug-addled, rebellious lifestyle had already led to a divorce from wife Melinda Merryweather, a Ford Agency model, actress and art designer, but Gale’s death seemed to push him over the edge from reckless to beyond help. He descended into a depression and drug addiction that lasted decades, ruining his surfing career and alienating him from everyone but his closest friends until only a few years ago.

Now 67, Hynson is muscular and trim from long days spent shaping boards for mostly Japanese customers. He still has a full head of hair, which is pulled back over his scalp into a short Native American-style braid. He’s wearing a black T-shirt adorned with a red Chinese dragon, dusty black jeans and rugged work boots. His face is full of color and breaks easily into a self-deprecating grin. Gone are the gaunt physique and haggard expression on display in photographs taken of him just a decade ago, when People profiled him in an embarrassing article titled “The Endless Bummer.” (The story noted that just a few weeks before Endless Summer 2 was released, Hynson was serving jail time for drug possession.)

It was during one of Hynson’s numerous jail stints, at some point in the 1980s—he’s not sure what year or why he was in jail—that somebody suggested he use his free time to write, a suggestion that, two decades later, led to Transcendental Memories of a Surf Rebel, an autobiography Hynson co-wrote with Donna Klaasen that was released this month by the Dana Point-based Endless Dreams Publishing. Among other things, the book divulges that Hynson, who has never spoken publicly about the Brotherhood, wasn’t just pals with them, but actually instructed them in the art of using surfboards to smuggle drugs.

“The last time I’d been in jail, I’d started reading for the first time in my life,” Hynson recalls of his autobiographical efforts. “And on this stretch, I just got obsessed with writing.” By the mid-1990s, Hynson had cranked out hundreds of pages of handwritten memoirs, all of it scrawled in pencil on jailhouse paper, which he eventually shared with a few friends at the surf shop down the street from where he now lives, a half-mile from the beach in Encinitas. “A couple of people looked at it and said, ‘Michael, I know you can understand this, but I look at it and I can’t understand a word,’” he says.

Hynson remembers glancing down at the first draft of his autobiography. For the first time, he realized that, after the first few pages, his magnum opus consisted of nothing but incomprehensible chicken-scratch scrawl, less a series of words and punctuation marks than a never-ending pattern of zigzag lines, like heart-monitor readings. “It was just so dysfunctional,” he says, chuckling.

* * *

Unlike the blurry events of the past few decades, the highlights of Hynson’s early life are still very vivid in his mind. Michael Lear Hynson was born in the Northern California coastal town of Crescent City in 1942, a Navy brat whose father survived kamikaze attacks as a radioman in World War II. Mike grew up in San Diego and Hawaii, never staying in one place long enough to make friends. His thrill-seeking lifestyle began while living with his mother at a trailer park when he was just 2 years old.

One morning, he crawled out the door while his mother wasn’t looking and discovered that the trailer next door had moved. He grabbed a 250-volt electrical plug that was lying on the ground and stuck it in his mouth. According to Hynson, the shock split his tongue and made it hard for him to learn how to speak. “I developed my own unique way of talking, and sometimes, I mumble and stumble,” he says. “Then, when I was 5, I was climbing these stairs at Imperial Beach, and this friend of mine had a hammer in his hand. My mother said something behind us, and he turned, and the claw of the hammer went right into the temple of my head.”

The next thing Hynson knew, he was being flown by helicopter to San Diego’s nearby naval base. He remembers floating above himself, looking down at his body surrounded by doctors, all of whom left the room. “I remember being really comfortable and just tripping, you know,” he says, “and then my mother turned around to leave the room, and I screamed into my body, ‘Where are you going?’ And my mother goes, ‘He’s alive!’ and the doctors came back in, and they got me back.” Hynson says he likes to joke that the hammer incident explains why he often seems to lose his train of thought nowadays. “Everybody who knows me knows that I go off on tangents,” he says. “But I’m just making an excuse for myself.”

Hynson spent most of his elementary-school years in Honolulu, where, he says, he never picked up a surfboard. It wasn’t until he was in junior-high school in San Diego that he took up surfing with some older kids who surfed at Pacific Beach, called themselves the Sultans and wore matching purple-nylon jackets. After watching the older kids a few times, he borrowed a board. Hynson recalls standing up on his first wave, not realizing how fast he was moving until he looked at the nearby pier and saw wooden posts rushing by in a blur. “I’ll never forget it,” he says. “It was so far out. I couldn’t sleep, and I just got into it, borrowing boards and stealing them and everything.”

Stealing surfboards is how Hynson met the man who would give him his first big break in the world of surfboard shaping, Hobie Alter, an early surf pioneer and inventor of the Hobie Cat, which is now the world’s top-selling small catamaran. “I first met Mike when he stole some of my boards,” Alter says. “The cops wanted to press charges, but Linda Benson, one of the finest surfer gals, called me and said Mike wasn’t that bad.” Alter agreed to drop the charges if Hynson would return the boards and later gave him a job as a shaper.

Hynson’s first board was an 11-foot plank of balsa wood that he spotted while collecting weeds in the front yard of a house in Mission Beach. The board’s owner told him he could have the board if he wanted it, so Hynson and a friend lugged it to the friend’s garage, where Hynson began whittling away. “I had no idea what I was doing, and his parents were getting angry because of all this dust and resin and mess, but it turned out to be a 7-foot-11-inch board. It was a hot little board, and everyone loved it who rode it.”

Hynson suddenly found his board-shaping skills very much in demand. He became a top shaper for Gordon and Smith Surfboards in San Diego, where he designed and produced his trademark “RedFin” boards. He also began hanging out with all the best surfers in Southern California, including Corky Carroll, Phil Edwards, Nat Young and Robert August. “As a surfer, Mike was very good,” recalls Carroll, now TheOrange County Register’s surfing columnist. “He was not a guy that you had to worry about beating you in a contest, but he knew how to ride a wave. He also had a kind of charisma about him that seemed to attract ‘followers,’ so to speak.”

One person who began following Hynson’s surf career was Bruce Brown, a film director who, by the early 1960s, was filming all the big surf contests in Southern California and Hawaii. According to Hynson, Brown was getting tired of the fact that all the surf movies being made showed the same group of surfers on the same group of waves. “There was no story to any of these movies,” Hynson says. Brown came up with the concept of taking two surfers—one blond and right-footed (Hynson) and one dark-haired goofy-footer—August fit the part—and following them around the world, from California to Europe and Africa, in search of the perfect wave.

The details of their epic quest, which culminates with Hynson surfing a beautiful right-breaking wave at Cape St. Francis in South Africa, are familiar to anyone who has seen The Endless Summer, which remains iconic more than 40 years later. The film not only exposed the sport to a nationwide audience, helping export the industry beyond California and Hawaii, but it also helped shift the sport itself from a handful of well-known beaches to a constant quest for pristine waves in exotic locales. Hynson recalls the trip as one of the most fun adventures in his life, although part of the sense of adventure was the fact that he smuggled an ounce of pot with him as he flew around the world.

“I was young, stupid and loaded,” Hynson says. “I smoked pot everywhere. I had a roll of bennies, which I took with me also, so when we had to drive somewhere, guess who stayed up all night?”

Before the movie was released theatrically in 1966, Hynson accompanied Brown and August, as well as several other surf legends, including Carroll, on a nationwide road trip to promote the film. “We’d go into towns, and every time we’d stop for gas, Corky and I would jump out and go skateboarding,” Hynson says. “We really caused a scene because skateboarding hadn’t reached the inner part of the States yet.” As the trip wore on, the audiences were growing larger, and before Hynson realized it, the movie had become a hit. (At latest count, The Endless Summer has grossed $30 million.) Hynson claims that Brown had promised him and August that if the movie did well, everyone would share in the good fortune.

“It wasn’t until I grabbed Robert and went to LA and talked to a lawyer that I realized this guy was fucking me left and right,” Hynson says. In fact, Hynson had only become suspicious after his then-girlfriend Merryweather, whom he had just met at San Diego’s Windansea beach, asked him about his allowing Brown to use his likeness on film. “He’d never signed a release,” says Merryweather, now a civic activist in La Jolla. Merryweather’s father, Hubert, was the president of Arizona’s state senate; Barry Goldwater was her godfather. “I told Mike my father knew a great lawyer up in Hollywood, and let’s go up and see him.”

Hynson brought August with him to see the attorney, who insisted they each deserved a third of the profit from The Endless Summer. Hynson claims Brown refused to do that, instead offering each surfer $5,000, a new car and help getting set up in business. While August accepted the deal, Hynson says, he refused. (Neither Brown nor August responded to written requests for comment for this story, but Alter says Brown gave Hynson the gift of fame he still enjoys. “Nobody knew who Mike was back then,” he says. “Bruce took all the risk, and I’ve never met anybody more forthright and honest.”) The dispute ended Hynson’s friendships with Brown and, eventually, August. Enraged by what he felt was Brown’s betrayal, Hynson dropped out for a while, leaving California with Merryweather to spend half a year surfing big waves on Oahu’s North Shore.

* * *

One of the surfers Hynson got to know in Hawaii was Chuck Mundell, a high-school dropout from Huntington Beach. Mundell admired Hynson and wanted him to meet a good friend of his named John Griggs, who was living with a bunch of friends in a stone building in Orange County’s Modjeska Canyon. Griggs and his friends, most of whom were former boozers, brawlers and heroin addicts from Anaheim, had begun experimenting with a new drug that Griggs had stolen at gunpoint from a Hollywood film producer: lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD).

Until October 1966, acid was legal in California, and Griggs and his group, who called themselves the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, believed that just as it had cured them of their addictions and violent behavior, it could also transform American society into a glorious utopia. They were heavily influenced by Harvard professor Timothy Leary, he of the famous exhortation “Turn on, tune in, drop out”—and who would later describe Griggs as the “holiest person who has ever lived in this country.”

Before Griggs invited Leary to join his group, which in early 1967 moved south to Laguna Canyon, to a neighborhood Griggs would christen “Dodge City” because of the constant skirmishes with the local forces of law and order, Hynson was Griggs’ most famous disciple. “Griggs had gold flashing out of his eyes and tongue, these words; he was just a magical little guy,” Hynson says. Accompanied by Merryweather, Hynson dropped his first acid with Griggs and several other Brotherhood members at Black’s Beach near La Jolla.

The experience brought him back to the hospital room where he’d nearly died as a child. It took Hynson a few trips to get beyond that near-death experience, but when that happened, he felt reborn with a new sense of spiritual purpose. “Those guys turned me on,” he says. “Things were happening. I remember Johnny and I walking down Haight-Ashbury [in San Francisco], and he got some acid from somebody, and the whole street was loaded with people doing their own hippie thing. It was really going on.”

Griggs had a plan: open a psychedelic spiritual and cultural center in Laguna Beach that would turn the town into a Southern California version of Haight-Ashbury. To finance the construction of Mystic Arts World, the store that would serve as that center, Griggs relied on cash from the Brotherhood’s burgeoning marijuana-smuggling operation.

“One day, I walked into this warehouse with Johnny and saw 50 tons of pot,” Hynson says. “I wasn’t supposed to see it, but I was there. I remember thinking, ‘It’s not going to get any better than this, and it’s not going to get any worse.’”

But Hynson had another idea for how Griggs could raise money: Why not use surfboards to smuggle hash from the Middle East or India? After all, nobody knew anything about surfing in India, so customs wouldn’t know if, for example, a surfboard weighed 20 or 30 pounds more than it should. Hynson suggested the idea to Griggs’ friend Dave Hall, who promptly borrowed a board and set off for Nepal, returning a few weeks later with the board—and the best hash anyone in Laguna Beach had ever smoked.

On his next trip, Hall invited Hynson to come along, which is how Hynson found himself struggling to fill three surfboards with hash oil late one night in New Delhi. The trip was a success, and the cash raised helped make Griggs’ dream a reality. “I wasn’t going to sell it or anything,” Hynson says. “I just gave it to those guys, and it bankrolled Mystic Arts. It was an honor, you know.”

* * *

During the next several years, the Brotherhood of Eternal Love established itself as both America’s top hashish-smuggling ring—with up to a dozen hash-stuffed Volkswagen buses and Land Rovers being shipped back from Afghanistan at any given moment—and the country’s top LSD-distribution ring. Leary moved to Laguna Beach and later accompanied Griggs to a mountain commune in Idyllwild, where Griggs died of an overdose of crystallized psilocybin in August 1969. Hynson stayed away from Dodge City as much as possible because Leary and the Brotherhood attracted too much heat.

He let his guard down once, however, when he and Merryweather sped through Laguna Canyon smoking a joint. A cop pulled them over, smelled the weed and arrested them both. At the station, the officer rifled through Merryweather’s belongings. “In my purse, I had a little Buddha, a prayer book and beads, some patchouli oil and incense, and a Murine bottle full of LSD,” Merryweather recalls. “The cop ingested it through his fingers and never got around to booking us.” In the morning, another officer arrived at the station, slack-jawed at the sight of his colleague, who reeked of patchouli, sitting with glazed eyes in front of a Buddha. “They let us the hell out of there right away,” Hynson says.

Not surprisingly, much of the late 1960s is a blur to Hynson. “It’s a fog,” he says. “There are a few years when I know I was there, but I don’t know what happened.” Although Griggs’ untimely death saddened Hynson, he’d already become best friends with a talented young surfer who also happened to be Dodge City’s biggest drug dealer, John Gale. In 1969, the two opened their own company, Rainbow Surfboards. Theirs were among the first truly shredding shortboards to hit the waves in Southern California and Hawaii. “Mike was one of the surfboard shapers in the 1960s who could make boards that worked,” recalls Carroll. “There were better craftsmen around, guys who could make ‘perfect boards,’ but Mike had the gift to make ones that just rode great.’”

Rainbow Surfboards got an unexpected publicity boost from Jimi Hendrix and Chuck Wein, a member of Andy Warhol’s so-called Factory whom Merryweather had befriended while working as a model in New York. In 1972, while Hynson and Merryweather were living in Maui—where most of the Brotherhood had relocated after Laguna Beach became too hot—Merryweather suggested to Wein that he direct a Jimi Hendrix concert movie in Maui and even introduced him to Hendrix’s manager, Michael Jefferey.

“Chuck wanted to make a movie that was going to have surfing, healers, vegetarians, New Age people, even a space woman,” Merryweather says. “Jimi was going to play the music because he was at the top of his game, and Michael was going to surf because he was at the top of his game.” The result, 1972’s Rainbow Bridge, was billed as a Hendrix concert film because the concert Hendrix played in Maui provides the ending of the movie, much of which actually features surfing by Hynson and his friends, goofy-foot hotshot Dave Nuuhiwa and Leslie Potts. “Gale refused to be in the movie, because he didn’t want to have his face on camera,” Hynson recalls.

The film’s most notorious scene features Hynson and Potts ripping open a Rainbow Surfboard to reveal a stash of hash, a stunt that takes place under a Richard Nixon poster that reads, “Would You Buy a Used Car From This Man?” When the film opened in Laguna Beach, Hynson gave Gale all the tickets as a birthday present. Half of the audience was rumored to be narcs. “The room smoked up so much you couldn’t see the stage,” Hynson says. “We had all these Rainbow Surfboards up on the stage, and when the movie showed the board being opened up, it got the police crazy. They were constantly on our ass. Anybody who had a Rainbow Surfboard got pulled over.”

* * *

A few months after Rainbow Bridge came out, a multi-agency task force arrested dozens of members of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love in California, Oregon and Maui, including Gale, who spent the next several months in prison. “He wasn’t in for long,” Hynson says. “He was like a rabbit.” But thanks in part to the Brotherhood’s legendary secrecy, the police never knew Hynson’s role in the group. Once Gale got out of prison, the two continued to sell surfboards and market the Rainbow brand by opening a Rainbow Juice bar in La Jolla with help from Merryweather. But the business folded after just a few years. “We didn’t shortchange anything,” Merryweather says. “We got an accounting firm and figured out we were paying people 25 cents to eat the avocado sandwiches.”

Meanwhile, Gale had become the biggest cocaine broker in California. Hynson says he didn’t know the full extent of Gale’s business dealings, but he does recall visiting his friend’s house one time when Gale suddenly remembered that a truck full of Colombian marijuana was on its way from Florida. He also recalls that whenever he rode in Gale’s car, someone always seemed to be following them. “Not for long, though,” Hynson says. “Gale didn’t stick around long enough for anyone to chase him.”

On June 2, 1982, Gale perished when the car he was driving, Hynson’s Mercedes, went off the road in Dana Point. Hynson remains convinced someone—either the cops or rival criminals—was chasing his friend. The tragedy ended Rainbow Surfboards (it’s recently been reincarnated under new ownership) and left Hynson financially strapped. “If you ever had a business project and you’re wondering whatever happened to it, it’s probably because the other guy is dead,” Hynson jokes.

Gale’s death devastated Hynson, says Merryweather. “I wasn’t with him at the time, but people told me they’d never seen Michael take anything so bad. He just really went sideways.”

Hynson spent the next two decades broke, strung out on coke and crystal methamphetamine, bouncing between jail and sleeping in alleys and garages in San Diego. “I got tripped up on my probation, you see,” he says, his voice trailing off as it often does when he attempts to make sense out of what happened to his life. “You know, it just snowballed. I hit rock-bottom, and then stayed there for a while.”

Hynson isn’t exactly sure how he finally managed to pull himself out of the downward spiral, although he credits ex-wife Merryweather and current girlfriend Carol Hannigan with being “angels” in his life. “It’s just been a gradual process of coming back to reality, and I haven’t stopped since,” he says. “One day, I realized I had a driver’s license with my own address and a telephone number. I even had a bank account. That’s when I realized I was back in society again.”

Thanks to the booming market for American-designed surfboards in Japan, Hynson is doing brisk business there. “There’s really no money in surfboards,” he says. “But thank God for the Japanese.” Meanwhile, Hynson hopes to sell the first 1,000 signed copies of his book for $350 each, which would raise enough cash to print many thousands of additional copies. Eventually, he wants to help publish art books by local artists such as Lance Jost and Bill Ogden, whom he’s known since his Laguna Beach days. “The more books we sell, the more the price goes down,” he says. “I don’t have any money right now, but I’m taking every cent I have, and we are just going to snowball this thing. If I can just get some juice, I’m going to have some fun.”

Nick Schou’, Orange Sunshine: The Brotherhood of Eternal Love and Its Quest to Spread Peace, Love, and Acid to the World, Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press.

http://www.gaudiya-repercussions.com/index.php?showtopic=2161&mode=threaded&pid=48222

Yes, there are links between the brotherhood and Iskcon [Hare Krishnas] and must have been made at least when Iskcon was established in Laguna Beach. How could any ashram in Laguna at the time, in 1969, have not had members who involved in the brotherhood who were established there? Bhakta dasa in his memoirs of his time in Laguna Beach and later LA, mentions how he first came across a devotee at Mystic Arts World. This place, a shop cum meditation room and meeting place, was one of the brotherhood’s main centres. Bhakta dasa also mentions how there was a picture above the shop front door of Prabhupada.

Rishabadev das was also linked to them, according to Nori Muster’s Betrayal of the Spirit, where I first found out about Iskcon-brotherhood links. He was involved with the independent latter day member of the brotherhood, Alexander Kulik. Unfortunately by this time the brotherhood had become corrupted as the counter culture in general had, with heavier drugs and violence. This link between Iskcon LA and Laguna Beach with Kulik was exposed in the press in 1977, the year Prabhupada pased on. It was in the LA media. Maybe you can obtain these articles through your library over there in the states. I’ve tried over here but without more money to hire researchers it is not possible.

Of course if the brotherhood became involved with Iskcon management structure covertly at all, any instance of devotee drug smuggling would be a likely candidate to link up with them, as big hash dealers were inevitably involved with them, especially in California. Nori also mentions that Jayatirtha dasa was a member too. He certainly later on espoused the use of psychedelics with Krishna consciousness and called them the same name as the brotherhood, sacraments.

Here's a short synopsis of Nori’s account she had derived from various newspapers and not to mention also her time in Iskcon PR in LA during Rameshvara dasa’s mIskcon-management.