The Hippies

The Hippies

By Hunter S. Thompson

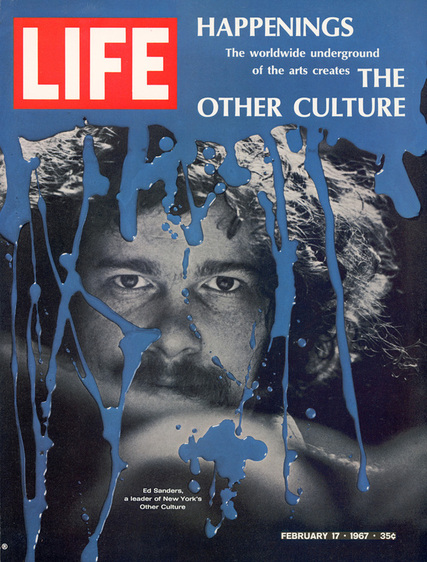

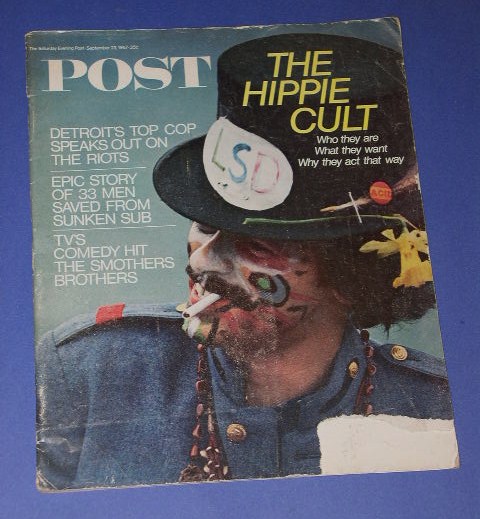

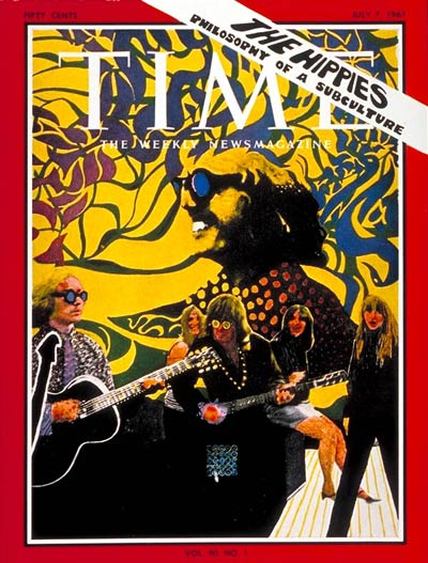

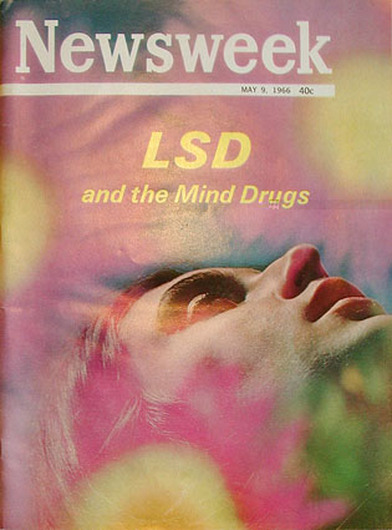

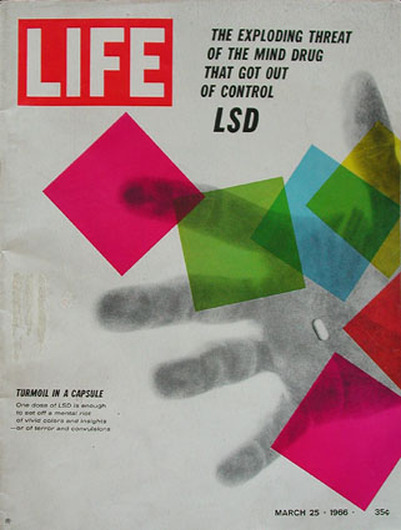

The best year to be a hippie was 1965, but then there was not much to write about, because not much was happening in public and most of what was happening in private was illegal. The real year of the hippie was 1966, despite the lack of publicity, which in 1967 gave way to a nationwide avalanche—in Look, Life, Time, Newsweek, the Atlantic, the New York Times, the Saturday Evening Post, and even the Aspen Illustrated News, which did a special issue on hippies in August of 1967 and made a record sale of all but 6 copies of a 3,500-copy press run. But 1967 was not really a good year to be a hippie. It was a good year for salesmen and exhibitionists who called themselves hippies and gave colorful interviews for the benefit of the mass media, but serious hippies, with nothing to sell, found that they had little to gain and a lot to lose by becoming public figures. Many were harassed and arrested for no other reason than their sudden identification with a so-called cult of sex and drugs. The publicity rumble, which seemed like a joke at first, turned into a menacing landslide. So quite a few people who might have been called the original hippies in 1965 had dropped out of sight by the time hippies became a national fad in 1967.

Ten years earlier the Beat Generation went the same confusing route. From 1955 to about 1959 there were thousands of young people involved in a thriving bohemian subculture that was only an echo by the time the mass media picked it up in 1960. Jack Kerouac was the novelist of the Beat Generation in the same way that Ernest Hemingway was the novelist of the Lost Generation, and Kerouac's classic "beat" novel, On the Road, was published in 1957. Yet by the time Kerouac began appearing on television shows to explain the "thrust" of his book, the characters it was based on had already drifted off into limbo, to await their reincarnation as hippies some five years later. (The purest example of this was Neal Cassidy [Cassady], who served as a model for Dean Moriarity in On the Road and also for McMurphy in Ken Kesey's One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest.)

Publicity follows reality, but only up to the point where a new kind of reality, created by publicity, begins to emerge. So the hippie in 1967 was put in the strange position of being an anti-culture hero at the same time as he was also becoming a hot commercial property. His banner of alienation appeared to be planted in quicksand. The very society he was trying to drop out of began idealizing him. He was famous in a hazy kind of way that was not quite infamy but still colorfully ambivalent and vaguely disturbing. Despite the mass media publicity, hippies still suffer—or perhaps not—from a lack of definition. The Random House Dictionary of the English Language was a best seller in 1966, the year of its publication, but it had no definition for "hippie."

The closest it came was a definition of "hippy": "having big hips; a hippy girl." Its definition of "hip" was closer to contemporary usage. "Hip" is a slang word, said Random House, meaning "familiar with the latest ideas, styles, developments, etc.; informed, sophisticated, knowledgeable [?]." That question mark is a sneaky but meaningful piece of editorial comment. Everyone seems to agree that hippies have some kind of widespread appeal, but nobody can say exactly what they stand for. Not even the hippies seem to know, although some can be very articulate when it comes to details. "I love the whole world," said a 23-year-old girl in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury district, the hippies' world capital. "I am the divine mother, part of Buddha, part of God, part of everything. "I live from meal to meal. I have no money, no possessions.

Money is beautiful only when it's flowing; when it piles up, it's a hang-up. We take care of each other. There's always something to buy beans and rice for the group, and someone always sees that I get 'grass' [marijuana] or 'acid' [LSD]. I was in a mental hospital once because I tried to conform and play the game. But now I'm free and happy." She was then asked whether she used drugs often. "Fairly," she replied. "When I find myself becoming confused I drop out and take a dose of acid. It's a short cut to reality; it throws you right into it. Everyone should take it, even children. Why shouldn't they be enlightened early, instead of waiting till they're old? Human beings need total freedom. That's where God is at. We need to shed hypocrisy, dishonesty, and phoniness and go back to the purity of our childhood values."

The next question was "Do you ever pray?" "Oh yes," she said. "I pray in the morning sun. It nourishes me with its energy so I can spread my love and beauty and nourish others. I never pray for anything; I don't need anything. Whatever turns me on is a sacrament: LSD, sex, my bells, my colors.... That's the holy communion, you dig?" That's about the most definitive comment anybody's ever going to get from a practicing hippie. Unlike beatniks, many of whom were writing poems and novels with the idea of becoming second-wave Kerouacs or Allen Ginsbergs, the hippie opinion makers have cultivated among their followers a strong distrust of the written word. Journalists are mocked, and writers are called "type freaks." Because of this stylized ignorance, few hippies are really articulate.

They prefer to communicate by dancing, or touching, or extrasensory perception (ESP). They talk, among themselves, about "love waves" and "vibrations" ("vibes") that come from other people. That leaves a lot of room for subjective interpretation, and therein lies the key to the hippies' widespread appeal. This is not to say that hippies are universally loved. From coast to coast, the forces of law and order have confronted the hippies with extreme distaste. Here are some representative comments from a Denver, Colo., police lieutenant. Denver, he said, was becoming a refuge for "long-haired, vagrant, antisocial, psychopathic, dangerous drug users, who refer to themselves as a 'hippie subculture'—a group which rebels against society and is bound together by the use and abuse of dangerous drugs and narcotics."

They range in age, he continued, from 13 to the early 20's, and they pay for their minimal needs by "mooching, begging, and borrowing from each other, their friends, parents, and complete strangers.... It is not uncommon to find as many as 20 hippies living together in one small apartment, in communal fashion, with their garbage and trash piled halfway to the ceiling in some cases." One of his co-workers, a Denver detective, explained that hippies are easy prey for arrests, since "it is easy to search and locate their drugs and marijuana because they don't have any furniture to speak of, except for mattresses lying on the floor. They don't believe in any form of productivity," he said, "and in addition to a distaste for work, money, and material wealth, hippies believe in free love, legalized use of marijuana, burning draft cards, mutual love and help, a peaceful planet, and love for love's sake. They object to war and believe that everything and everybody—except the police—are beautiful." Many so-called hippies shout "love" as a cynical password and use it as a smokescreen to obscure their own greed, hypocrisy, or mental deformities.

Many hippies sell drugs, and although the vast majority of such dealers sell only enough to cover their own living expenses, a few net upward of $20,000 a year. A kilogram (2.2 pounds) of marijuana, for instance, costs about $35 in Mexico. Once across the border it sells (as a kilo) for anywhere from $150 to $200. Broken down into 34 ounces, it sells for $15 to $25 an ounce, or $510 to $850 a kilo. The price varies from city to city, campus to campus, and coast to coast. "Grass" is generally cheaper in California than it is in the East. The profit margin becomes mind-boggling—regardless of the geography—when a $35 Mexican kilogram is broken down into individual "joints," or marijuana cigarettes, which sell on urban street corners for about a dollar each. The risk naturally increases with the profit potential.

It's one thing to pay for a trip to Mexico by bringing back three kilos and selling two in a circle of friends: The only risk there is the possibility of being searched and seized at the border. But a man who gets arrested for selling hundreds of "joints" to high school students on a St. Louis street corner can expect the worst when his case comes to court. The British historian Arnold Toynbee, at the age of 78, toured San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury district and wrote his impressions for the London Observer. "The leaders of the Establishment," he said, "will be making the mistake of their lives if they discount and ignore the revolt of the hippies—and many of the hippies' nonhippie contemporaries—on the grounds that these are either disgraceful wastrels or traitors, or else just silly kids who are sowing their wild oats."

Toynbee never really endorsed the hippies; he explained his affinity in the longer focus of history. If the human race is to survive, he said, the ethical, moral, and social habits of the world must change: The emphasis must switch from nationalism to mankind. And Toynbee saw in the hippies a hopeful resurgence of the basic humanitarian values that were beginning to seem to him and other long-range thinkers like a tragically lost cause in the war-poisoned atmosphere of the 1960's. He was not quite sure what the hippies really stood for, but since they were against the same things he was against (war, violence, and dehumanized profiteering), he was naturally on their side, and vice versa.

There is a definite continuity between the beatniks of the 1950's and the hippies of the 1960's. Many hippies deny this, but as an active participant in both scenes, I'm sure it's true. I was living in Greenwich Village in New York City when the beatniks came to fame during 1957 and 1958. I moved to San Francisco in 1959 and then to the Big Sur coast for 1960 and 1961. Then after two years in South America and one in Colorado, I was back in San Francisco, living in the Haight-Ashbury district, during 1964, 1965, and 1966. None of these moves was intentional in terms of time or place; they just seemed to happen.

When I moved into the Haight-Ashbury, for instance, I'd never even heard that name. But I'd just been evicted from another place on three days' notice, and the first cheap apartment I found was on Parnassus Street, a few blocks above Haight. At that time the bars on what is now called "the street" were predominantly Negro. Nobody had ever heard the word "hippie," and all the live music was Charlie Parker-type jazz. Several miles away, down by the bay in the relatively posh and expensive Marina district, a new and completely unpublicized nightclub called the Matrix was featuring an equally unpublicized band called the Jefferson Airplane. At about the same time, hippie author Ken Kesey (One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, 1962, and Sometimes a Great Notion, 1964) was conducting experiments in light, sound, and drugs at his home at La Honda, in the wooded hills about 50 miles south of San Francisco.

As the result of a network of circumstance, casual friendships, and connections in the drug underworld, Kesey's band of Merry Pranksters was soon playing host to the Jefferson Airplane and then to the Grateful Dead, another wildly electric band that would later become known on both coasts—along with the Airplane—as the original heroes of the San Francisco acid-rock sound. During 1965, Kesey's group staged several much-publicized Acid Tests, which featured music by the Grateful Dead and free Kool-Aid spiked with LSD. The same people showed up at the Matrix, the Acid Tests, and Kesey's home in La Honda. They wore strange, colorful clothes and lived in a world of wild lights and loud music. These were the original hippies.

It was also in 1965 that I began writing a book on the Hell's Angels, a notorious gang of motorcycle outlaws who had plagued California for years, and the same kind of weird coincidence that jelled the whole hippie phenomenon also made the Hell's Angels part of the scene. I was having a beer with Kesey one afternoon in a San Francisco tavern when I mentioned that I was on my way out to the headquarters of the Frisco Angels to drop off a Brazilian drum record that one of them wanted to borrow. Kesey said he might as well go along, and when he met the Angels he invited them down to a weekend party in La Honda. The Angels went and thereby met a lot of people who were living in the Haight-Ashbury for the same reason I was (cheap rent for good apartments). People who lived two or three blocks from each other would never realize it until they met at some pre-hippie party. But suddenly everybody was living in the Haight-Ashbury, and this accidental unity took on a style of its own. All that it lacked was a label, and the San Francisco Chronicle quickly came up with one.

These people were "hippies," said the Chronicle, and, lo, the phenomenon was launched. The Airplane and the Grateful Dead began advertising their sparsely attended dances with psychedelic posters, which were given away at first and then sold for $1 each, until finally the poster advertisements became so popular that some of the originals were selling in the best San Francisco art galleries for more than $2,000. By this time both the Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead had gold-plated record contracts, and one of the Airplane's best numbers, "White Rabbit," was among the best-selling singles in the nation. By that time, too, the Haight-Ashbury had become such a noisy mecca for freaks, drug peddlers, and curiosity seekers that it was no longer a good place to live. Haight Street was so crowded that municipal buses had to be rerouted because of the traffic jams.

At the same time, the "Hashbury" was becoming a magnet for a whole generation of young dropouts, all those who had canceled their reservations on the great assembly line: the high-rolling, soul-bending competition for status and security in the ever-fattening—yet ever-narrowing—American economy of the late 1960's. As the rewards of status grew richer, the competition grew stiffer. A failing grade in math on a high school report card carried far more serious implications than simply a reduced allowance: It could alter a boy's chances of getting into college and, on the next level, of getting the "right job."

As the economy demanded higher and higher skills, it produced more and more technological dropouts. The main difference between hippies and other dropouts was that most hippies were white and voluntarily poor. Their backgrounds were largely middle class; many had gone to college for a while before opting out for the "natural life"—an easy, unpressured existence on the fringe of the money economy. Their parents, they said, were walking proof of the fallacy of the American notion that says "work and suffer now; live and relax later." The hippies reversed that ethic. "Enjoy life now," they said, "and worry about the future tomorrow."

Most take the question of survival for granted, but in 1967, as their enclaves in New York and San Francisco filled up with penniless pilgrims, it became obvious that there was simply not enough food and lodging. A partial solution emerged in the form of a group called the Diggers, sometimes referred to as the "worker-priests" of the hippie movement. The Diggers are young and aggressively pragmatic; they set up free lodging centers, free soup kitchens, and free clothing distribution centers. They comb hippie neighborhoods, soliciting donations of everything from money to stale bread and camping equipment. In the Hashbury, Diggers' signs are posted in local stores, asking for donations of hammers, saws, shovels, shoes, and anything else that vagrant hippies might use to make themselves at least partially self-supporting.

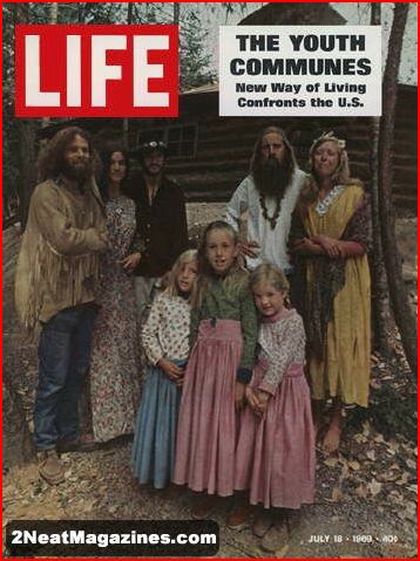

The Hashbury Diggers were able, for a while, to serve free meals, however meager, each afternoon in Golden Gate Park, but the demand soon swamped the supply. More and more hungry hippies showed up to eat, and the Diggers were forced to roam far afield to get food. The concept of mass sharing goes along with the American Indian tribal motif that is basic to the whole hippie movement. The cult of tribalism is regarded by many as the key to survival. Poet Gary Snyder, one of the hippie gurus, or spiritual guides, sees a "back to the land" movement as the answer to the food and lodging problem. He urges hippies to move out of the cities, form tribes, purchase land, and live communally in remote areas.

By early 1967 there were already a half dozen functioning hippie settlements in California, Nevada, Colorado, and upstate New York. They were primitive shack-towns, with communal kitchens, half-alive fruit and vegetable gardens, and spectacularly uncertain futures. Back in the cities the vast majority of hippies were still living from day to day. On Haight Street those without gainful employment could easily pick up a few dollars a day by panhandling. The influx of nervous voyeurs and curiosity seekers was a handy money-tree for the legion of psychedelic beggars. Regular visitors to the Hashbury found it convenient to keep a supply of quarters in their pockets so that they wouldn't have to haggle about change. The panhandlers were usually barefoot, always young, and never apologetic. They would share what they collected anyway, so it seemed entirely reasonable that strangers should share with them. Unlike the beatniks, few hippies are given to strong drink. Booze is superfluous in the drug culture, and food is regarded as a necessity to be acquired at the least possible expense.

A "family" of hippies will work for hours over an exotic stew or curry, but the idea of paying three dollars for a meal in a restaurant is out of the question. Some hippies work, others live on money from home, and many get by with part-time jobs, loans from old friends, or occasional transactions on the drug market. In San Francisco the post office is a major source of hippie income. Jobs like sorting mail don't require much thought or effort. The sole support of one "clan" (or "family," or "tribe") was a middle-aged hippie known as Admiral Love, of the Psychedelic Rangers, who had a regular job delivering special delivery letters at night. There was also a hippie-run employment agency on Haight Street; anyone needing temporary labor or some kind of specialized work could call up and order whatever suitable talents were available at the moment.

Significantly, the hippies have attracted more serious criticism from their former compatriots of the New Left than they have from what would seem to be their natural antagonists on the political right. Conservative William Buckley's National Review, for instance, says, "The hippies are trying to forget about original sin and it may go hard with them hereafter." The National Review editors completely miss the point that serious hippies have already dismissed the concept of original sin and that the idea of a hereafter strikes them as a foolish, anachronistic joke. The concept of some vengeful God sitting in judgment on sinners is foreign to the whole hippie ethic. Its God is a gentle abstract deity not concerned with sin or forgiveness but manifesting himself in the purest instincts of "his children." The New Left brand of criticism has nothing to do with theology.

Until 1964, in fact, the hippies were so much a part of the New Left that nobody knew the difference. "New Left," like "hippie" and "beatnik," was a term coined by journalists and headline writers, who need quick definitions of any subject they deal with. The term came out of the student rebellion at the University of California's Berkeley campus in 1964 and 1965. What began as a Free Speech Movement in Berkeley soon spread to other campuses in the East and Midwest and was seen in the national press as an outburst of student activism in politics, a healthy confrontation with the status quo. On the strength of the free speech publicity, Berkeley became the axis of the New Left. Its leaders were radical, but they were also deeply committed to the society they wanted to change.

A prestigious University of California faculty committee said the activists were the vanguard of a "moral revolution among the young," and many professors approved. Those who were worried about the radicalism of the young rebels at least agreed with the direction they were taking: civil rights, economic justice, and a new morality in politics. The anger and optimism of the New Left seemed without limits. The time had come, they said, to throw off the yoke of a politico-economic establishment that was obviously incapable of dealing with new realities. The year of the New Left publicity was 1965. About the same time there was mention of something called the pot (marijuana) left. Its members were generally younger than the serious political types, and the press dismissed them as a frivolous gang of "druggies" and sex "kooks" who were only along for the ride. Yet as early as the spring of 1966, political rallies in Berkeley were beginning to have overtones of music, madness, and absurdity. Dr. Timothy Leary—the ex-Harvard professor whose early experiments with LSD made him, by 1966, a sort of high priest, martyr, and public relations man for the drug—was replacing Mario Savio, leader of the Free Speech Movement, as the number-one underground hero.

Students who were once angry activists began to lie back in their pads and smile at the world through a fog of marijuana smoke or to dress like clowns and Indians and stay "zonked" on LSD for days at a time. The hippies were more interested in dropping out of society than they were in changing it. The break came in late 1966, when Ronald Reagan was elected governor of California by almost a million-vote plurality. In that same November the GOP gained 50 seats in Congress and served a clear warning on the Johnson administration that despite all the headlines about the New Left, most of the electorate was a lot more conservative than the White House antennae had indicated. The lesson was not lost on the hippies, many of whom considered themselves at least part-time political activists. One of the most obvious casualties of the 1966 elections was the New Left's illusion of its own leverage.

The radical-hippie alliance had been counting on the voters to repudiate the "right-wing, warmonger" elements in Congress, but instead it was the "liberal" Democrats who got stomped. The hippies saw the election returns as brutal confirmation of the futility of fighting the Establishment on its own terms. There had to be a whole new scene, they said, and the only way to do it was to make the big move—either figuratively or literally—from Berkeley to the Haight-Ashbury, from pragmatism to mysticism, from politics to dope, from the involvement of protest to the peaceful disengagement of love, nature, and spontaneity.

The mushrooming popularity of the hippie scene was a matter of desperate concern to the young political activists. They saw a whole generation of rebels drifting off to a drugged limbo, ready to accept almost anything as long as it came with enough "soma" (as Aldous Huxley named the psychic escape drug of the future in his science-fiction novel Brave New World, 1932). New Left writers and critics at first commended the hippies for their frankness and originality. But it soon became obvious that few hippies cared at all for the difference between political left and right, much less between the New Left and the Old Left.

"Flower Power" (their term for the power of love), they said, was nonpolitical. And the New Left quickly responded with charges that hippies were "intellectually flabby," that they lacked "energy" and "stability," that they were actually "nihilists" whose concept of love was "so generalized and impersonal as to be meaningless." And it was all true. Most hippies are too drug oriented to feel any sense of urgency beyond the moment.

Their slogan is "Now," and that means instantly. Unlike political activists of any stripe, hippies have no coherent vision of the future—which might or might not exist. The hippies are afflicted by an enervating sort of fatalism that is, in fact, deplorable. And the New Left critics are heroic, in their fashion, for railing at it. But the awful possibility exists that the hippies may be right, that the future itself is deplorable—and so why not live for Now? Why not reject the whole fabric of American society, with all its obligations, and make a separate peace? The hippies believe they are asking this question for a whole generation—and echoing the doubts of an older generation. Source: 1968 Collier’s Year Book.

Appears in United States (History); Hippie; Protests in the 1960s

By Hunter S. Thompson

The best year to be a hippie was 1965, but then there was not much to write about, because not much was happening in public and most of what was happening in private was illegal. The real year of the hippie was 1966, despite the lack of publicity, which in 1967 gave way to a nationwide avalanche—in Look, Life, Time, Newsweek, the Atlantic, the New York Times, the Saturday Evening Post, and even the Aspen Illustrated News, which did a special issue on hippies in August of 1967 and made a record sale of all but 6 copies of a 3,500-copy press run. But 1967 was not really a good year to be a hippie. It was a good year for salesmen and exhibitionists who called themselves hippies and gave colorful interviews for the benefit of the mass media, but serious hippies, with nothing to sell, found that they had little to gain and a lot to lose by becoming public figures. Many were harassed and arrested for no other reason than their sudden identification with a so-called cult of sex and drugs. The publicity rumble, which seemed like a joke at first, turned into a menacing landslide. So quite a few people who might have been called the original hippies in 1965 had dropped out of sight by the time hippies became a national fad in 1967.

Ten years earlier the Beat Generation went the same confusing route. From 1955 to about 1959 there were thousands of young people involved in a thriving bohemian subculture that was only an echo by the time the mass media picked it up in 1960. Jack Kerouac was the novelist of the Beat Generation in the same way that Ernest Hemingway was the novelist of the Lost Generation, and Kerouac's classic "beat" novel, On the Road, was published in 1957. Yet by the time Kerouac began appearing on television shows to explain the "thrust" of his book, the characters it was based on had already drifted off into limbo, to await their reincarnation as hippies some five years later. (The purest example of this was Neal Cassidy [Cassady], who served as a model for Dean Moriarity in On the Road and also for McMurphy in Ken Kesey's One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest.)

Publicity follows reality, but only up to the point where a new kind of reality, created by publicity, begins to emerge. So the hippie in 1967 was put in the strange position of being an anti-culture hero at the same time as he was also becoming a hot commercial property. His banner of alienation appeared to be planted in quicksand. The very society he was trying to drop out of began idealizing him. He was famous in a hazy kind of way that was not quite infamy but still colorfully ambivalent and vaguely disturbing. Despite the mass media publicity, hippies still suffer—or perhaps not—from a lack of definition. The Random House Dictionary of the English Language was a best seller in 1966, the year of its publication, but it had no definition for "hippie."

The closest it came was a definition of "hippy": "having big hips; a hippy girl." Its definition of "hip" was closer to contemporary usage. "Hip" is a slang word, said Random House, meaning "familiar with the latest ideas, styles, developments, etc.; informed, sophisticated, knowledgeable [?]." That question mark is a sneaky but meaningful piece of editorial comment. Everyone seems to agree that hippies have some kind of widespread appeal, but nobody can say exactly what they stand for. Not even the hippies seem to know, although some can be very articulate when it comes to details. "I love the whole world," said a 23-year-old girl in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury district, the hippies' world capital. "I am the divine mother, part of Buddha, part of God, part of everything. "I live from meal to meal. I have no money, no possessions.

Money is beautiful only when it's flowing; when it piles up, it's a hang-up. We take care of each other. There's always something to buy beans and rice for the group, and someone always sees that I get 'grass' [marijuana] or 'acid' [LSD]. I was in a mental hospital once because I tried to conform and play the game. But now I'm free and happy." She was then asked whether she used drugs often. "Fairly," she replied. "When I find myself becoming confused I drop out and take a dose of acid. It's a short cut to reality; it throws you right into it. Everyone should take it, even children. Why shouldn't they be enlightened early, instead of waiting till they're old? Human beings need total freedom. That's where God is at. We need to shed hypocrisy, dishonesty, and phoniness and go back to the purity of our childhood values."

The next question was "Do you ever pray?" "Oh yes," she said. "I pray in the morning sun. It nourishes me with its energy so I can spread my love and beauty and nourish others. I never pray for anything; I don't need anything. Whatever turns me on is a sacrament: LSD, sex, my bells, my colors.... That's the holy communion, you dig?" That's about the most definitive comment anybody's ever going to get from a practicing hippie. Unlike beatniks, many of whom were writing poems and novels with the idea of becoming second-wave Kerouacs or Allen Ginsbergs, the hippie opinion makers have cultivated among their followers a strong distrust of the written word. Journalists are mocked, and writers are called "type freaks." Because of this stylized ignorance, few hippies are really articulate.

They prefer to communicate by dancing, or touching, or extrasensory perception (ESP). They talk, among themselves, about "love waves" and "vibrations" ("vibes") that come from other people. That leaves a lot of room for subjective interpretation, and therein lies the key to the hippies' widespread appeal. This is not to say that hippies are universally loved. From coast to coast, the forces of law and order have confronted the hippies with extreme distaste. Here are some representative comments from a Denver, Colo., police lieutenant. Denver, he said, was becoming a refuge for "long-haired, vagrant, antisocial, psychopathic, dangerous drug users, who refer to themselves as a 'hippie subculture'—a group which rebels against society and is bound together by the use and abuse of dangerous drugs and narcotics."

They range in age, he continued, from 13 to the early 20's, and they pay for their minimal needs by "mooching, begging, and borrowing from each other, their friends, parents, and complete strangers.... It is not uncommon to find as many as 20 hippies living together in one small apartment, in communal fashion, with their garbage and trash piled halfway to the ceiling in some cases." One of his co-workers, a Denver detective, explained that hippies are easy prey for arrests, since "it is easy to search and locate their drugs and marijuana because they don't have any furniture to speak of, except for mattresses lying on the floor. They don't believe in any form of productivity," he said, "and in addition to a distaste for work, money, and material wealth, hippies believe in free love, legalized use of marijuana, burning draft cards, mutual love and help, a peaceful planet, and love for love's sake. They object to war and believe that everything and everybody—except the police—are beautiful." Many so-called hippies shout "love" as a cynical password and use it as a smokescreen to obscure their own greed, hypocrisy, or mental deformities.

Many hippies sell drugs, and although the vast majority of such dealers sell only enough to cover their own living expenses, a few net upward of $20,000 a year. A kilogram (2.2 pounds) of marijuana, for instance, costs about $35 in Mexico. Once across the border it sells (as a kilo) for anywhere from $150 to $200. Broken down into 34 ounces, it sells for $15 to $25 an ounce, or $510 to $850 a kilo. The price varies from city to city, campus to campus, and coast to coast. "Grass" is generally cheaper in California than it is in the East. The profit margin becomes mind-boggling—regardless of the geography—when a $35 Mexican kilogram is broken down into individual "joints," or marijuana cigarettes, which sell on urban street corners for about a dollar each. The risk naturally increases with the profit potential.

It's one thing to pay for a trip to Mexico by bringing back three kilos and selling two in a circle of friends: The only risk there is the possibility of being searched and seized at the border. But a man who gets arrested for selling hundreds of "joints" to high school students on a St. Louis street corner can expect the worst when his case comes to court. The British historian Arnold Toynbee, at the age of 78, toured San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury district and wrote his impressions for the London Observer. "The leaders of the Establishment," he said, "will be making the mistake of their lives if they discount and ignore the revolt of the hippies—and many of the hippies' nonhippie contemporaries—on the grounds that these are either disgraceful wastrels or traitors, or else just silly kids who are sowing their wild oats."

Toynbee never really endorsed the hippies; he explained his affinity in the longer focus of history. If the human race is to survive, he said, the ethical, moral, and social habits of the world must change: The emphasis must switch from nationalism to mankind. And Toynbee saw in the hippies a hopeful resurgence of the basic humanitarian values that were beginning to seem to him and other long-range thinkers like a tragically lost cause in the war-poisoned atmosphere of the 1960's. He was not quite sure what the hippies really stood for, but since they were against the same things he was against (war, violence, and dehumanized profiteering), he was naturally on their side, and vice versa.

There is a definite continuity between the beatniks of the 1950's and the hippies of the 1960's. Many hippies deny this, but as an active participant in both scenes, I'm sure it's true. I was living in Greenwich Village in New York City when the beatniks came to fame during 1957 and 1958. I moved to San Francisco in 1959 and then to the Big Sur coast for 1960 and 1961. Then after two years in South America and one in Colorado, I was back in San Francisco, living in the Haight-Ashbury district, during 1964, 1965, and 1966. None of these moves was intentional in terms of time or place; they just seemed to happen.

When I moved into the Haight-Ashbury, for instance, I'd never even heard that name. But I'd just been evicted from another place on three days' notice, and the first cheap apartment I found was on Parnassus Street, a few blocks above Haight. At that time the bars on what is now called "the street" were predominantly Negro. Nobody had ever heard the word "hippie," and all the live music was Charlie Parker-type jazz. Several miles away, down by the bay in the relatively posh and expensive Marina district, a new and completely unpublicized nightclub called the Matrix was featuring an equally unpublicized band called the Jefferson Airplane. At about the same time, hippie author Ken Kesey (One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, 1962, and Sometimes a Great Notion, 1964) was conducting experiments in light, sound, and drugs at his home at La Honda, in the wooded hills about 50 miles south of San Francisco.

As the result of a network of circumstance, casual friendships, and connections in the drug underworld, Kesey's band of Merry Pranksters was soon playing host to the Jefferson Airplane and then to the Grateful Dead, another wildly electric band that would later become known on both coasts—along with the Airplane—as the original heroes of the San Francisco acid-rock sound. During 1965, Kesey's group staged several much-publicized Acid Tests, which featured music by the Grateful Dead and free Kool-Aid spiked with LSD. The same people showed up at the Matrix, the Acid Tests, and Kesey's home in La Honda. They wore strange, colorful clothes and lived in a world of wild lights and loud music. These were the original hippies.

It was also in 1965 that I began writing a book on the Hell's Angels, a notorious gang of motorcycle outlaws who had plagued California for years, and the same kind of weird coincidence that jelled the whole hippie phenomenon also made the Hell's Angels part of the scene. I was having a beer with Kesey one afternoon in a San Francisco tavern when I mentioned that I was on my way out to the headquarters of the Frisco Angels to drop off a Brazilian drum record that one of them wanted to borrow. Kesey said he might as well go along, and when he met the Angels he invited them down to a weekend party in La Honda. The Angels went and thereby met a lot of people who were living in the Haight-Ashbury for the same reason I was (cheap rent for good apartments). People who lived two or three blocks from each other would never realize it until they met at some pre-hippie party. But suddenly everybody was living in the Haight-Ashbury, and this accidental unity took on a style of its own. All that it lacked was a label, and the San Francisco Chronicle quickly came up with one.

These people were "hippies," said the Chronicle, and, lo, the phenomenon was launched. The Airplane and the Grateful Dead began advertising their sparsely attended dances with psychedelic posters, which were given away at first and then sold for $1 each, until finally the poster advertisements became so popular that some of the originals were selling in the best San Francisco art galleries for more than $2,000. By this time both the Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead had gold-plated record contracts, and one of the Airplane's best numbers, "White Rabbit," was among the best-selling singles in the nation. By that time, too, the Haight-Ashbury had become such a noisy mecca for freaks, drug peddlers, and curiosity seekers that it was no longer a good place to live. Haight Street was so crowded that municipal buses had to be rerouted because of the traffic jams.

At the same time, the "Hashbury" was becoming a magnet for a whole generation of young dropouts, all those who had canceled their reservations on the great assembly line: the high-rolling, soul-bending competition for status and security in the ever-fattening—yet ever-narrowing—American economy of the late 1960's. As the rewards of status grew richer, the competition grew stiffer. A failing grade in math on a high school report card carried far more serious implications than simply a reduced allowance: It could alter a boy's chances of getting into college and, on the next level, of getting the "right job."

As the economy demanded higher and higher skills, it produced more and more technological dropouts. The main difference between hippies and other dropouts was that most hippies were white and voluntarily poor. Their backgrounds were largely middle class; many had gone to college for a while before opting out for the "natural life"—an easy, unpressured existence on the fringe of the money economy. Their parents, they said, were walking proof of the fallacy of the American notion that says "work and suffer now; live and relax later." The hippies reversed that ethic. "Enjoy life now," they said, "and worry about the future tomorrow."

Most take the question of survival for granted, but in 1967, as their enclaves in New York and San Francisco filled up with penniless pilgrims, it became obvious that there was simply not enough food and lodging. A partial solution emerged in the form of a group called the Diggers, sometimes referred to as the "worker-priests" of the hippie movement. The Diggers are young and aggressively pragmatic; they set up free lodging centers, free soup kitchens, and free clothing distribution centers. They comb hippie neighborhoods, soliciting donations of everything from money to stale bread and camping equipment. In the Hashbury, Diggers' signs are posted in local stores, asking for donations of hammers, saws, shovels, shoes, and anything else that vagrant hippies might use to make themselves at least partially self-supporting.

The Hashbury Diggers were able, for a while, to serve free meals, however meager, each afternoon in Golden Gate Park, but the demand soon swamped the supply. More and more hungry hippies showed up to eat, and the Diggers were forced to roam far afield to get food. The concept of mass sharing goes along with the American Indian tribal motif that is basic to the whole hippie movement. The cult of tribalism is regarded by many as the key to survival. Poet Gary Snyder, one of the hippie gurus, or spiritual guides, sees a "back to the land" movement as the answer to the food and lodging problem. He urges hippies to move out of the cities, form tribes, purchase land, and live communally in remote areas.

By early 1967 there were already a half dozen functioning hippie settlements in California, Nevada, Colorado, and upstate New York. They were primitive shack-towns, with communal kitchens, half-alive fruit and vegetable gardens, and spectacularly uncertain futures. Back in the cities the vast majority of hippies were still living from day to day. On Haight Street those without gainful employment could easily pick up a few dollars a day by panhandling. The influx of nervous voyeurs and curiosity seekers was a handy money-tree for the legion of psychedelic beggars. Regular visitors to the Hashbury found it convenient to keep a supply of quarters in their pockets so that they wouldn't have to haggle about change. The panhandlers were usually barefoot, always young, and never apologetic. They would share what they collected anyway, so it seemed entirely reasonable that strangers should share with them. Unlike the beatniks, few hippies are given to strong drink. Booze is superfluous in the drug culture, and food is regarded as a necessity to be acquired at the least possible expense.

A "family" of hippies will work for hours over an exotic stew or curry, but the idea of paying three dollars for a meal in a restaurant is out of the question. Some hippies work, others live on money from home, and many get by with part-time jobs, loans from old friends, or occasional transactions on the drug market. In San Francisco the post office is a major source of hippie income. Jobs like sorting mail don't require much thought or effort. The sole support of one "clan" (or "family," or "tribe") was a middle-aged hippie known as Admiral Love, of the Psychedelic Rangers, who had a regular job delivering special delivery letters at night. There was also a hippie-run employment agency on Haight Street; anyone needing temporary labor or some kind of specialized work could call up and order whatever suitable talents were available at the moment.

Significantly, the hippies have attracted more serious criticism from their former compatriots of the New Left than they have from what would seem to be their natural antagonists on the political right. Conservative William Buckley's National Review, for instance, says, "The hippies are trying to forget about original sin and it may go hard with them hereafter." The National Review editors completely miss the point that serious hippies have already dismissed the concept of original sin and that the idea of a hereafter strikes them as a foolish, anachronistic joke. The concept of some vengeful God sitting in judgment on sinners is foreign to the whole hippie ethic. Its God is a gentle abstract deity not concerned with sin or forgiveness but manifesting himself in the purest instincts of "his children." The New Left brand of criticism has nothing to do with theology.

Until 1964, in fact, the hippies were so much a part of the New Left that nobody knew the difference. "New Left," like "hippie" and "beatnik," was a term coined by journalists and headline writers, who need quick definitions of any subject they deal with. The term came out of the student rebellion at the University of California's Berkeley campus in 1964 and 1965. What began as a Free Speech Movement in Berkeley soon spread to other campuses in the East and Midwest and was seen in the national press as an outburst of student activism in politics, a healthy confrontation with the status quo. On the strength of the free speech publicity, Berkeley became the axis of the New Left. Its leaders were radical, but they were also deeply committed to the society they wanted to change.

A prestigious University of California faculty committee said the activists were the vanguard of a "moral revolution among the young," and many professors approved. Those who were worried about the radicalism of the young rebels at least agreed with the direction they were taking: civil rights, economic justice, and a new morality in politics. The anger and optimism of the New Left seemed without limits. The time had come, they said, to throw off the yoke of a politico-economic establishment that was obviously incapable of dealing with new realities. The year of the New Left publicity was 1965. About the same time there was mention of something called the pot (marijuana) left. Its members were generally younger than the serious political types, and the press dismissed them as a frivolous gang of "druggies" and sex "kooks" who were only along for the ride. Yet as early as the spring of 1966, political rallies in Berkeley were beginning to have overtones of music, madness, and absurdity. Dr. Timothy Leary—the ex-Harvard professor whose early experiments with LSD made him, by 1966, a sort of high priest, martyr, and public relations man for the drug—was replacing Mario Savio, leader of the Free Speech Movement, as the number-one underground hero.

Students who were once angry activists began to lie back in their pads and smile at the world through a fog of marijuana smoke or to dress like clowns and Indians and stay "zonked" on LSD for days at a time. The hippies were more interested in dropping out of society than they were in changing it. The break came in late 1966, when Ronald Reagan was elected governor of California by almost a million-vote plurality. In that same November the GOP gained 50 seats in Congress and served a clear warning on the Johnson administration that despite all the headlines about the New Left, most of the electorate was a lot more conservative than the White House antennae had indicated. The lesson was not lost on the hippies, many of whom considered themselves at least part-time political activists. One of the most obvious casualties of the 1966 elections was the New Left's illusion of its own leverage.

The radical-hippie alliance had been counting on the voters to repudiate the "right-wing, warmonger" elements in Congress, but instead it was the "liberal" Democrats who got stomped. The hippies saw the election returns as brutal confirmation of the futility of fighting the Establishment on its own terms. There had to be a whole new scene, they said, and the only way to do it was to make the big move—either figuratively or literally—from Berkeley to the Haight-Ashbury, from pragmatism to mysticism, from politics to dope, from the involvement of protest to the peaceful disengagement of love, nature, and spontaneity.

The mushrooming popularity of the hippie scene was a matter of desperate concern to the young political activists. They saw a whole generation of rebels drifting off to a drugged limbo, ready to accept almost anything as long as it came with enough "soma" (as Aldous Huxley named the psychic escape drug of the future in his science-fiction novel Brave New World, 1932). New Left writers and critics at first commended the hippies for their frankness and originality. But it soon became obvious that few hippies cared at all for the difference between political left and right, much less between the New Left and the Old Left.

"Flower Power" (their term for the power of love), they said, was nonpolitical. And the New Left quickly responded with charges that hippies were "intellectually flabby," that they lacked "energy" and "stability," that they were actually "nihilists" whose concept of love was "so generalized and impersonal as to be meaningless." And it was all true. Most hippies are too drug oriented to feel any sense of urgency beyond the moment.

Their slogan is "Now," and that means instantly. Unlike political activists of any stripe, hippies have no coherent vision of the future—which might or might not exist. The hippies are afflicted by an enervating sort of fatalism that is, in fact, deplorable. And the New Left critics are heroic, in their fashion, for railing at it. But the awful possibility exists that the hippies may be right, that the future itself is deplorable—and so why not live for Now? Why not reject the whole fabric of American society, with all its obligations, and make a separate peace? The hippies believe they are asking this question for a whole generation—and echoing the doubts of an older generation. Source: 1968 Collier’s Year Book.

Appears in United States (History); Hippie; Protests in the 1960s

http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1967/09/the-flowering-of-the-hippies/306619/

The Flowering of the Hippies

"It was easy to see that the young men who were hippies on Haight Street wore beards and long hair and sometimes earrings and weird-o granny eye-glasses, and that they were generally dirty."

Mark Harris, Sept. 1 1967

The hippie "scene" on Haight Street in San Francisco was so very visual that photographers came from everywhere to shoot it, reporters came from everywhere to write it up with speed, and oportunists came from everywhere to exploit its drug addiction, its sexual possibility, and its political or social ferment. Prospective hippies came from everywhere for one "summer of love" or maybe longer, some older folk to indulge their latent hippie tendencies, and the police to contain, survey, or arrest. "Haight"—old Quaker name—rhymed with "hate," but hippies held that the theme of the street was love, and the best of hippies like the best of visitors and the best of the police, hoped to reclaim and distill the best promise of a movement which might yet invigorate American movement everywhere. It might, by resurrecting the word "love,", and giving it a refreshened definition, open the national mind, as if by the chemical LSD, to the hypocrisy of violence and prejudice in a nation dedicated to peace and accord.

It was easier to see than understand: the visual was so discordant that tourists drove with their cars locked and an alarmed citizenrry beseeched the police to clean it out.

It was easy to see that the young men who were hippies on Haight Street wore beards and long hair and sometimes earrings and weird-o granny eye-glasses, that they were barefoot or in sandals, and that they were generally dirty. A great many of the young men, by design or by accident, resembled Jesus Christ, whose name came up on campaign pins or lavatory walls or posters or bumper stickers. Are you Bombing With Me, Baby Jesus. Jesus Is God's Atom Bomb.

The script was "psychedelic." That is to say, it was characterized by flourishes, spirals, and curlicues in camouflaged tones—blues against purples, pinks against reds—as if the hippie behind the message weren't really sure he wanted to say what he was saying. It was an item of hippie thought that speech was irrelevant. You Don't Say Love You Do It. Those Who Speak Don't Know Those Who Know Don't Speak. But it was also my suspicion that hippies would speak when they could; meanwhile, their muteness suggested doubt. In one shop—the wall was dominated by an old movie advertisement—Ronald Reagan and June Travis in Love Is in the Air (Warner Brothers), their faces paper-white, blank, drained. I asked the hippie at the counter why it was there, but she didn't trust herself to try. "It's what you make of it," she said.

It was easy to see that the young women who were hippies were draped, not dressed; that they, too, were dirty from toe to head; that they looked unwell, pale, sallow, hair hung down in strings unwashed. Or they wore jeans, men's T-shirts over brassieres. When shoes were shoes the laces were missing or trailing, gowns were sacks, and sacks were gowns. If You Can't Eat It Wear It.

A fashion model was quoted in a newspaper as saying, "They don't really exist," who meant to say, of course, "I wish they didn't." The young ladies were experimenting in drugs, in sexual license, living in communal quarters furnished with mattresses. Praise The Pill. Bless Our Pad. Girls who might have been in fashion were panhandling. "Sorry, I've got to go panhandle," I heard a hippie lady say, which was not only against the law but against the American creed, which holds that work is virtue, no matter what work you do. Hippie girls gave flowers to strangers, and they encouraged their dirty young men to avoid the war in Vietnam. Thou Shalt Not Kill This Means You. Caution: Military Service May Be Hazardous To Your Health.

The shops of the "hip" merchants were colorful and cordial. The "straight" merchants of Haight Street sold necessities, buf the hip shops smelled of incense, the walls were hung with posters and paintings, and the counters were laden with thousands of items of nonutilitarian nonsense—metal jewelry, glass beads, dirty pictures, "underground" magazines, photographs of old-time movie stars, colored chalk, dirty combs, kazoos, Halloween masks, fancy match boxes, odd bits of stained glass, and single shoes. Every vacant wall was a bulletin board for communication among people not yet quite settled ("Jack and Frank from Iowa leave a message here.")

The music everywhere was rock 'n' roll out of Beatles, folk, African drums, American pop, jazz, swing, and martial.

Anybody who was anybody among hippies had been arrested for something, or so he said—for "possession" (of drugs), for "contributing" (to the delinquency of a minor), for panhandling, for obstructing the sidewalk, and if for nothing else, for "resisting" (arrest). The principal cause of their conflict with the police was their smoking marijuana, probably harmless but definitely illegal. Such clear proof of the failure of the law to meet the knowledge of the age presented itself to the querulous minds of hippies as sufficient grounds to condemn the law complete.

Hippies thought they saw on Haight Street that everyone's eyes were filled with loving joy and giving, but the eyes of the hippies were often in fact sorrowful and frightened, for they had plunged themselves into an experiment they were uncertain they could carry through. Fortified by LSD (Better Living Through Chemistry), they had come far enough to see distance behind them, but no clear course ahead. One branch of their philosophy was Oriental concentration and meditation; now it often focused upon the question "How to kick" (drugs).

The ennobling idea of the hippies, forgotten or lost in the visual scene, diverted by chemistry, was their plan for community. For community had come. What kind of community, upon what model? Hippies wore brilliant Mexican chalecos, Oriental robes, and red-Indian headdress. They dressed as cowboys. They dressed as frontiersmen. They dressed as Puritans. Doubtful who they were, trying on new clothes, how could they know where they were going until they saw what fit? They wore military insignia. Among bracelets and bells they wore Nazi swastikas and the German Iron Cross, knowing, without knowing much more, that the swastika offended the Establishment, and no enemy of the Establishment could be all bad. They had been born, give or take a year or two, in the year of Hiroshima.

Once the visual scene was ignored, almost the first point of interest about the hippies was that they were middle-class American chilldren to the bone. To citizens inclined to alarm this was the thing most maddening, that these were not Negroes disaffected by color or immigrants by strangeness but boys and girls with white skins from the right side of the economy in all-American cities and towns from Honolulu to Baltimore. After regular educations, if only they'd want them, they could commute to fine jobs from the suburbs, and own nice houses with bathrooms, where they could shave and wash up.

Many hippies lived with the help of remittances from home, whose parents, so straight, so square, so seeming compliant, rejected, in fact, a great portion of that official American program rejected by the hippies in psychedelic script. The 19th Century Was A Mistake The 20th Century Is A Disaster. Even in arrest they found approval from their parents, who had taught them in years of civil rights and resistance to the war in Vietnam that authority was often questionable, sometimes despicable. George F. Babbitt, forty years before in Zenith, U.S.A., declared his hope, at the end of a famous book, that his son might go farther than Babbitt had dared along lines of break and rebellion.

When hippies first came to San Francisco they were an isolated minority, mistrustful, turned inward by drugs, lacking acquaintance beyond themselves. But they were spirited enough after all, to have fled from home, to have endured the discomforts of a cramped existence along Haight Street, proud enough to have endured the insults of the police, and alert enough to have identified the major calamities of their age.

In part a hoax of American journalism, known even to themselves only as they saw themselves in the media, they began at last, and especially with the approach of the "summer of love," to assess community, their quest, and themselves.

They slowly became, in the word that seemed to cover it, polarized, distinct in division among themselves between, on one hand, weekend or summertime hippies, and on the other, hippies for whom the visual scene was an insubstantial substitute for genuine community. The most perceptive or advanced among the hippies then began to undertake the labor of community which could be accomplished only behind the scene, out of the eye of the camera, beyond the will of the quick reporter.

The visual scene was four blocks along on Haight Street. Haight Street itself was nineteen, extending east two miles from Golden Gate Park, through the visual scene, through a portion of the Negro district known as the Fillmore, past the former campus of San Francisco State College, and flowing at its terminus into Market Street, into the straight city, across the Bay Bridge, and into that wider United States whose values the hippies were testing, whose traditions were their own propulsion in spite of their denials, and whose future the hippies might yet affect in singular ways unimagined by either those States or those hippies. From the corner of Haight and Ashbury Streets it was three miles to Broadway and Columbus, heart of North Beach, where the Beats had gathered ten years before.

The Haight-Ashbury district is a hundred square blocks of homes and parks. One of the parks is the Panhandle of Golden Gate, thrusting itself into the district, preserving, eight blocks long, a green and lovely relief unimpaired by prohibitions against free play by children or the free promenade of adults along its mall. Planted in pine, maple, redwood, and eucalyptus, its only serious resistance to natural things is a statue honoring William McKinley, but consigned to the farthest extremity, for which, in 1903, Theodore Roosevelt broke the ground.

The Panhandle is the symbolic and spiritual center of the district, its stay against confusion. On March 28, 1966, after a struggle of several years—and by a single vote of the San Francisco Supervisors—the residents of the Haight-Ashbury district were able to rescue the Panhandle from the bulldozer, which would have replaced it with a freeway assisting commuters to save six minutes between downtown and the Golden Gate Bridge.

In one of the few triumphs of neighborhood over redevelopment the power of the district lay in the spiritual and intellectual composition of its population, which tended toward firm views of the necessity to save six minutes and toward a skeptical view of the promise of "developers" to "plant it over" afterward. Apart from the Panhandle controversy, the people of the district had firm views clustering about the conviction that three-story Tudor and Victorian dwellings are preferable to skyscrapers, that streets should serve people before automobiles, that a neighborhood was meant for living as well as sleeping, that habitation implies some human dirt, that small shops foster human acquaintance as department stores don't, and that schools which are integrated are more educational than schools which are segregated.

One of the effects of the victory of the bulldozer would have been the obliteration of low-cost housing adjacent to the Panhandle, and therefore the disappearance of poorer people from the district. But the people of the Haight-Ashbury failed of enthusiasm. "Fair streets are better than silver," wrote Vachel Lindsay, leading hippie of Springfield, Illinois, half a century ago, and considered that part of his message central enough to carry it in psychedelic banners on the end pages of his Collected Poems:

Fair streets are better than silver.

Green parks are better than gold.

Bad public taste is mob law.

Good public taste is democracy.

A crude administration is damned already.

A bad designer is to that extent a bad citizen.

Let the best moods of the people rule. The Haight-Ashbury—to give it its San Francisco sound—had long been a favorite residential area for persons of liberal disposition in many occupations, in business, labor, the arts, the professions, and academic life. It had been equally hospitable to avant-garde expression, to racial diversity, and to the Okies and Arkies who came after World War II. Its polyglot population estimated at 30,000, was predominantly white, but it included Negroes and Orientals in sizable numbers and general distribution, and immigrants of many nations. Here William Saroyan and Erskine Caldwell had lived.

During the decade of the sixties it was a positive attraction to many San Franciscans who could easily have lived at "better addresses" but who chose the Haight-Ashbury for its congeniality and cultural range. Here they could prove to anyone who cared, and especially to their children, the possibilities of racial integration. The Haight-Ashbury was the only neighborhood in the nation, as far as I know, to send its own delegation—one white man, one Negro woman—to the civil rights March in Washington in 1963.

Wealth and comfort ascended with the hills, in the southern portion of the district. In the low, flat streets near the Panhandle, where the hippies lived, the residents were poorer, darker, and more likely to be of foreign extraction. There, too, students and young artists lived, and numbers of white families who had chosen the perils of integration above the loss of their proximity to the Panhandle. With the threat of the freeway many families had moved away and many stores had become vacant, and when the threat had passed, a vacuum remained.

The hippies came, lured by availability, low rents, low prices, and the spirit of historic openness. The prevailing weather was good in a city when weather varied with the contours of hills. Here a hippie might live barefoot most of the months of the year, lounge in sunswept doorways slightly out of the wind, and be fairly certain that politic liberals, bedeviled Negroes, and propertyless whites were more likely than neighbors elsewhere to admit him to community.

The mood of the Haight-Ashbury ranged from occasional opposition to the hippies to serene indifference, to tolerance, to interest, and to delight. As trouble increased between hippies and police, and as alarm increased elsewhere in the city, the Haight-Ashbury kept its head. It valued the passions of the young, especially when the young were, as hippies were, nonviolent. No doubt, at least among liberals, it saw something of its own earlier life in the lives of hippies.

Last March the Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood Council, formed in 1957 to meet a crisis similar to the Panhandle controversy, committed itself to a policy of extended patience. It declared that "we particularly resent the official position of law-enforcement agencies, as announced by [Police] Chief Cahill, that hippies are not an asset to the community. The chief has not distinguished among the many kinds of citizens who comprise the hippie culture.... War against a class of citizens, regardless of how they dress or choose to live, within the latitude of the law, is intolerable in a free society. We remember that regrettable history of officially condoned crusades against the Chinese population of San Francisco whose life style did not meet with the approval of the established community and whose lives and property were objects of terrorism and persecution."

If any neighborhood in America was prepared to accomodate the hippies, it was the Haight-Ashbury. On the heights and on the level rich and poor were by and large secure, open, liberal, pro-civil-rights, and in high proportion anti-war. Its U.S. congressman was Philip Burton, a firm and forthright liberal, and its California assembly-man was Willie Brown, a Negro of unquestioned intellect and integrity. Here the hippies might gain time to shape their message and translate to coherence the confusion of the visual scene. If hippies were unable to make, of all scenes, the Haight-Ashbury scene, then there was something wrong with them.

LYSERGIC ACID DIETHYLAMIDE The principle distinction between the hippies and every other endeavor in utopian community was LSD, which concentrated upon the liver, produced chemical change in the body, and thereby affected the brain. Whether LSD produced physical harm remained an argument, but its most ardent advocates and users (not always the same persons) never denied its potentially dangerous emotional effects. Those effects depended a great deal on the user's disposition. Among the hippies of San Franciso, LSD precipitated suicide and other forms of self-destructive or antisocial behavior. For some hippies it produced little or nothing, and was a disappointment. For many, it precipitated gorgeous hallucinations, a wide variety of sensual perceptions never before available to the user, and breathtaking panoramic visions of human and social perfection accompanied by profound insights into the user's own past.

It could be manufactured in large quantities by simple processes, like gin in a bathtub, easily carried about, and easily retained without detection. In liquid it was odorless and colorless; in powder it was minute. Its administration required no needles or other paraphernalia, and since it was taken orally, it left no "tracks" upon the body.

Technically it was nonaddictive, but it conspiciously induced in the user—the younger he was, the more so—a strong desire for another "trip": the pleasures of life under LSD exceeded the realities of sober perception. More far-reaching than liquor, quicker for insights than college or psychiatry, the pure and instant magic of LSD appeared for an interesting moment to capture the mind of the hippies. Everybody loved a panacea.

Their text was The Psychedelic Experience, by Leary, Metzner, and Alpert, "a manual based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead," whose jacket assured the reader that the book had been completed free of academic auspices. It was likely that the hippies' interest in the book lay, in any case, rather in its use as "manual" than in its historical reference.

Bob Dylan, favorite of many hippies, told in a line of song, "To live outside the law you must be honest." But hippies were Puritan Americans, gorged with moral purpose, and loath to confess that their captivation was basically the pursuit of pleasure. They therefore attached to the mystique of LSD the conviction that by opening their minds to chemical visions they were gaining insights from which society soon should profit.

Hippies themselves might have profited, as anyone might, from LSD in a clinical environment, but the direction of their confidence lay elsewhere, and they placed themselves beneath the supervision mainly of other hippies. Dialogue was confined among themselves, no light was shed upon the meaning of their visions, and their preoccupation became LSD itself—what it did to them last time, and what it might do next. Tool had become symbol, and symbol principle. If the hippie ideal of community failed, it would fail upon lines of a dull, familiar scheme: the means had become the end.

Far from achieving an exemplary community of their own, with connections to existing community, the hippies had achieved only, in the language of one of their vanguard, "a community of acid heads." If LSD was all the hippies talked about, the outlying community could hardly be blamed for thinking this was all they were. Visions of community seen under LSD had not been imparted to anyone, remaining visible only to hippies, or entering the visual scene only in the form of commentary upon LSD itself, jokes and claims for its efficacy growing shriller with the increase of dependence. But the argument had been that LSD inspired transcendence, that it was, as one hippie phrased it, "a stepping-stone to get out of your environment and look at it.

Under the influence of LSD hippies had written things down, or drawn pictures, but upon examination the writings or the pictures proved less perfect than they had appeared while the trip was on. Great utterances delivered under LSD were somehow unutterable otherwise. Great thoughts the hippies had thought under LSD they could never soberly convey, nor reproduce the startling new designs for happier social arrangements.

Two years after the clear beginnings of the hippies in San Francisco, a date established by the opening of the Psychedelic Shop, hippies and others had begun to recognize that LSD, if it had not failed, had surely not fully succeeded. ("We have serious doubts," said a Quaker report, "whether drugs offer the spiritual illumination which bears fruit in Christlike lives.") Perhaps, as some hippies claimed, their perceptions had quickened, carrying them forward to a point of social readiness. It had turned them on, then off.

Whatever the explanation, by the time of the "summer of love" their relationship with the surrounding community had badly deteriorated. The most obvious failure of perception was the hippies' failure to discriminate among elements of the Establishment, whether in the Haight-Ashbury or in San Francisco in general. Their paranoia was the paranoia of all youthful heretics. Even Paranoids Have Real Enemies. True. But they saw all the world as straight but them; all cops were brutes, and everyone else was an arm of the cops. Disaffiliating with all persons and all institutions but themselves, they disaffiliated with all possible foundations of community.

It was only partly true, as hippies complained, that "the Establishment isn't listening to us." The Establishment never listened to anyone until it was forced to. That segment of the Establishment known as the Haight-Ashbury, having welcomed the hippies with friendliness and hope, had listened with more courtesy to hippies than hippies had listened to the Haight-Ashbury.

Hippies had theories of community, theories of work, theories of child care, theories of creativity. Creative hippies were extremely creative about things the city and the district could do for them. For example, the city could cease harassing hippies who picked flowers in Golden Gate Park to give them away on Haight Street. The city replied that the flowers of Golden Gate Park were for all people—were community flowers—and suggested that hippies plant flowers of their own. Hippies imagined an all-powerful city presided over by an all-powerful mayor who, said a hippie, "wants to stop human growth." They imagined an all-powerful Board of Supervisors which with inexhaustible funds could solve all problems simultaneously if only it wanted to.

Their illusions, their unreason, their devil theories, their inexperience of life, and their failures of perception had begun to persuade even the more sympathetic elements of the Haight-Ashbury that the hippies perhaps failed of perception in general. The failure of the hippies to communicate reasonably cast doubt upon their reliability as observers, especially with respect to the most abrasive of all issues, their relationship with the police.

Was it merely proof of its basic old rigidity that the Haight-Ashbury believed that community implied social relief, that visions implied translation to social action? Squares Love, Too: Haight-Ashbury For All People. So read an answering campaign pin as friction increased. But the hippies, declining self-regulation, aloof, self-absorbed, dumped mountains of garbage on the Panhandle. The venereal rate of the Haight-Ashbury multiplied by six. (The hippies accused Dr. Ellis Sox of the health department of sexual repression.) The danger grew alarmingly of rats, food poisoning, hepatitis, pulmonary tuberculosis, and of meningitis caused by overcrowded housing. "If hippies don't want to observe city and state laws," said Dr. Sox, "let them at least observe a few natural laws."

Hippies behaved so much like visitors to the community that their neighbors, who intended to live in the district forever, questioned whether proclamations of community did not require, acts of community. Hippies had theories of love, which might have meant, at the simplest level, muting music for the benefit of neighbors who must rise in the morning for work. Would the Haight-Ashbury once again, if the emergency arose, expend years of its life to retain a Panhandle for hippies to dump their garbage on? Or would it abandon the hippies to the most primitive interpretations of law, permit their dispersion, and see their experiment end without beginning?

At no point was the hippies' failure to seek community so apparent as with relation to the Negroes of the district. With the passage of the civil rights movement from demonstrations to legal implementation excellent opportunities existed for the show of love. What grand new design in black and white had hippies seen under LSD? If Negroes were expected to share with hippies the gestures of love, then hippies ought to have shared with Negroes visions of equal rights.

The burdens of the Negroes of the district were real. Negro tenants desired the attention of the health department, desired the attention of agencies whom hippies monopolized with appeals for food and housing for the "summer of love." The needs of the Negroes, especially for jobs, appeared to Negroes a great deal more urgent than the needs of white middle-class hippies who had dropped out of affluence to play games of poverty in San Francisco. "Things should be given away free," said a Negro man in a public debate, "to people that really need them."

One afternoon, on Masonic Street, a hundred feet off Haight, I saw a Negro boy, perhaps twelve years old, repairing an old bicycle that had been repaired before. His tools lay on the sidewalk beside him, arranged in a systematic way, as if according to an order he had learned from his father. His face was intent, the work was complicated. Nearby, the hippies masqueraded. I mentioned to a lady the small boy at work, the big boys at play. "Yes," she said, "the hippies have usurped the prerogatives of children—to dress up and be irresponsible."

THE POLARIZATION OF THE HIPPIES A hippie record is entitled Notes From Underground. The hippie behind the counter told me that "underground" was a hippie word. He had not yet heard of Dostoevsky, whose title the record borrowed, or of the antislavery underground in America, or of the World War II underground in France. A movement which thought itself the world's first underground was bound to make mistakes it could have avoided by consultation with the past, and there was evidence that the hippies had begun to know it.

Nobody asked the hippies to accept or acknowledge the texts of the past. Their reading revealed their search for self-help, not conducted among the traditional books of the Western world but of the Orient—in I Ching and The Prophet, and in the novels of the German Hermann Hesse, especially the "Oriental" Siddhartha. Betrayed by science and reason, hippies indulged earnestly in the occult, the astrological, the mystical, the horoscopic, and the Ouija. Did hippies know that Ouija boards were a popular fad not long ago?

Or did they know that The Prophet of Kahlil Gibran, reprinted seventy-seven times since 1923, lies well within the tradition of American self-help subliterature? No sillier book exists, whose "prose poetry," faintly biblical, offers homiletic advice covering one by one all the departments of life (On Love, On Marriage, On Children, On Giving, On Eating and Drinking, On Work—on and on) in a manner so ambiguous as to permit the reader to interpret all tendencies as acceptable and to end by doing as he pleases, as if with the sanction of the prophet.

Hesse was a German, born in 1877, who turned consciously to romantic expression after age forty, but the wide interest of the hippies in Siddhartha is less conscious than Hesse's. To the hero's search for unity between self and nature they respond as German youth responded to Hesse, or as an earlier generation of Americans responded to the spacious, ambiguous outcry of Thomas Wolfe.

Inevitably, they were going through all these things twice, unaware of things gone through before. Inherent in everything printed or hanging in the visual scene on Haight Street was satirical rejection of cultural platitudes, but in the very form and style, of the platitudes themselves. Children of television, they parodied it, spoofing Batman, as if Batman mattered. The satire in which they rejoiced was television's own artistic outpost. The walls of Haight Street bore, at a better level, the stamp, of Mad magazine or collages satirizing the chaos of advertising: but anyone could see the same who turned the pages of Reader's Digest fast.